Case counts of monkeypox continue to grow worldwide, raising concerns about how people can protect themselves. So far, the World Health Organization reports that in 12 countries, 92 cases have been confirmed in this recent emergence of the virus, and 28 possible cases are still being investigated. What alarms public health officials about the recent outbreaks is that monkeypox is generally not common or known to circulate in these nations; it’s endemic in parts of central and western Africa, but not in the European and North American nations—including the U.S.—that are currently seeing an uptick in infections. The U.S. recorded its first case this year in Massachusetts on May 18, and officials from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said in a briefing on May 23 that the agency is working with state health departments in New York, Florida, and Utah to investigate four additional potential cases.

The good news is that an approved, effective, and relatively new monkeypox vaccine already exists. But do Americans need to get vaccinated?

The monkeypox vaccine

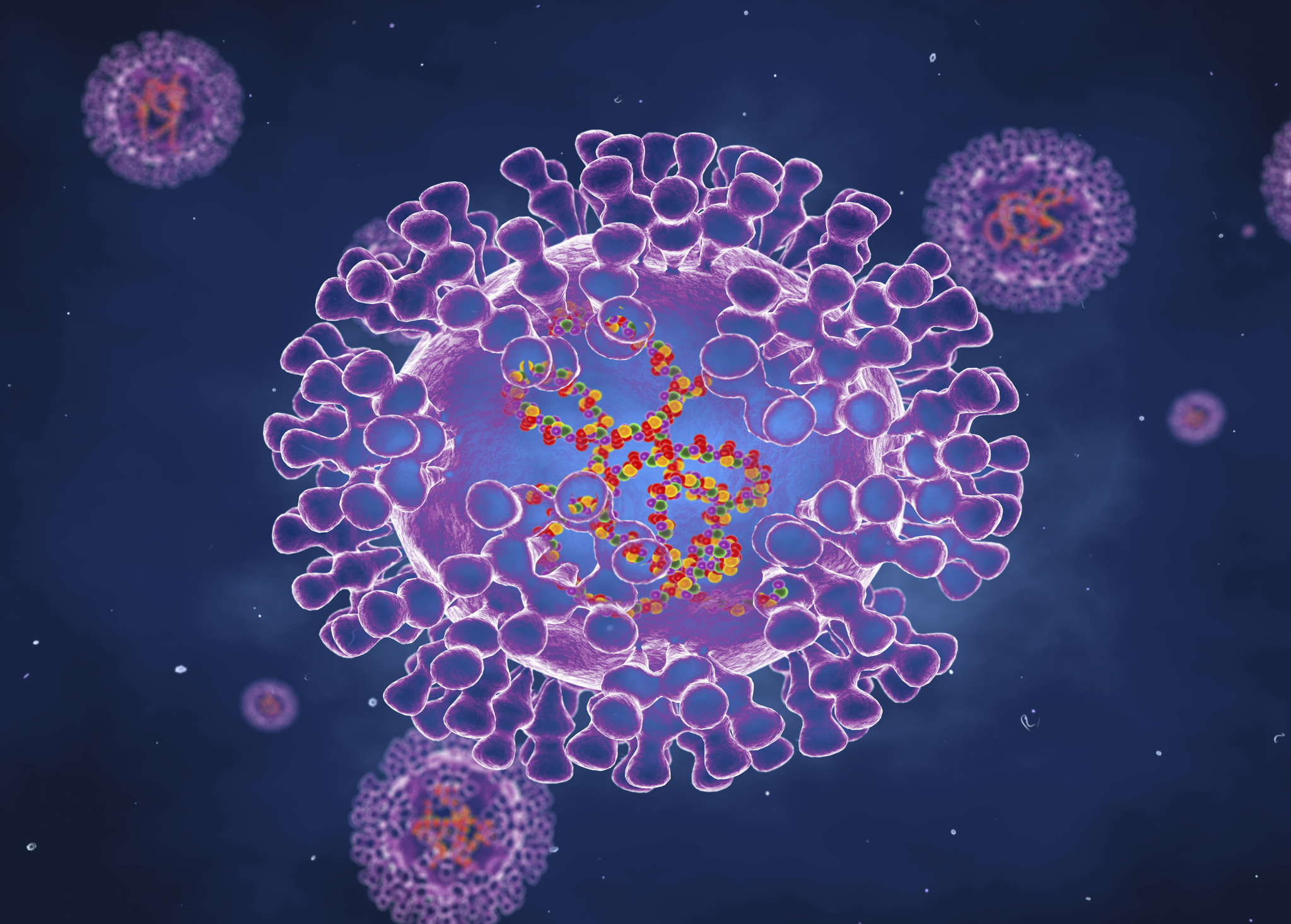

Made by the Danish company Bavarian Nordic and named Jynneos, the vaccine uses a live version of the smallpox virus that has been engineered so that it cannot replicate in the body or cause infection, but can still activate the immune system to mount defenses against both the smallpox and monkeypox viruses to protect people from getting infected. According to studies conducted among people who were vaccinated in Africa, where the virus has circulated for years, two doses of the vaccine, given 28 days apart, were up to 85% effective in protecting people from getting monkeypox. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2019 to protect against both smallpox and monkeypox.

Americans don’t routinely get vaccinated against either disease. But in November 2021, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) within the CDC considered the question of who should be immunized against monkeypox, since cases in the U.S. have occurred after people traveled to areas in Africa where the disease is endemic. After analyzing the available studies, the ACIP recommended that those at highest risk of exposure and infection—including scientists who work in labs that study monkeypox virus, first responders who may treat those occupational cases, and health care workers who care for infected patients—should receive the vaccine. The recommendations were accepted by CDC director Dr. Rochelle Walensky and published in the agency’s publication of record, the MMWR, on May 27, making them official.

“The ACIP did a very good job of considering all the different populations who might have occupational risks of exposure [to monkeypox],” says Brett Peterson, deputy chief of the pox virus and rabies branch of the CDC. But, he says, that was before the current clusters of cases, and the committee members focused primarily on how best to protect people at high occupational risk from getting infected, since there wasn’t a significant danger of cases in the wider population. The recommendations did not address potential community cases of monkeypox, and whether people other than those at high occupational risk of exposure should get vaccinated. But if cases continue to emerge, the agency may review the data and address that need if it becomes relevant.

A possible vaccination approach

Unlike with the COVID-19 vaccines, immunizing people against monkeypox likely won’t involve a mass campaign, because monkeypox isn’t as contagious or as easily spread as SARS-CoV-2. Monkeypox was discovered in 1958 and named after the colonies of monkeys, which were part of research studies, in which the virus was first identified. In recent years, human cases have been reported primarily in central and West African countries such as Nigeria and Cameroon, with the West African virus, which circulates widely in Nigeria, resulting in less severe disease than the central African version. As a poxvirus, its symptoms are similar to those of smallpox, and include fever, muscle aches, and headache. Unlike smallpox, however, monkeypox also causes the lymph nodes to swell, and several days after the initial fever, hallmark lesions start appearing throughout the body, eventually developing into larger fluid-filled vesicles and pustules before forming scabs. Most people with the disease recover without treatments after two to four weeks, although antiviral therapies could be helpful, especially for those with weakened immune systems. In the May 23 press briefing, CDC scientists noted that the data showing the efficacy of these antiviral treatments in human patients are still limited, and that most of the data supporting their use come from animal studies.

The virus can spread through a number of routes, the most common and direct being via breaks in the skin or contact with body fluids. Monkeypox and also transmit from one person to another through respiratory droplets from sneezes or saliva—although infection is less likely to occur this way and more likely to happen with direct contact with the virus-laden lesions.

That’s why vaccinating for monkeypox will most likely involve a version of what experts call a ring strategy, and focus on immunizing only those with contact with infected individuals. “If a case is reported in the country, a public health SWAT team goes out, finds out who the close contacts are of that first case, and vaccinates just those close contacts, and not the entire city or suburb,” says Dr. David Freedman, professor emeritus of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and president-elect of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. “Because monkeypox is not a virus that is spread mainly through respiratory transmission, you don’t see huge numbers of infected people. So you can do ring vaccination around the known cases.”

If that approach is used, “we have sufficient vaccine in the Strategic National Stockpile to vaccinate the entire U.S. population,” says Peterson. “I am confident that there is sufficient vaccine available for use in this situation.” The U.S.’s initial contract with Bavarian Nordic after the vaccine was approved called for 28 million doses of the vaccine to be provided for the stockpile over a number of years. But because some of those doses were delivered around 2019, some have expired, and the terms of the agreement require the company to replace expired doses with freshly manufactured ones.

Captain Jennifer McQuiston, deputy director of the division of high consequence pathogens and pathology at CDC, said during the press briefing that about 1,000 doses of the vaccine are currently available, and that Bavarian Nordic expects to ramp up production to increase that supply. In addition, on May 18, the U.S.’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), part of the Department of Health and Human Services, called in an existing order for up to 13 million additional frozen doses to add to that stockpile. The versions of the vaccine currently in storage were manufactured as a liquid and then frozen, which gives them a shorter shelf life, according to Peterson. The newer, freeze-dried versions are first turned into a powder that makes them more resistant to changes in temperature before they are reconstituted just before being injected. But these more shelf-stable vaccines won’t be available until 2023 and 2024.

McQuiston added that so far, officials at the Massachusetts Department of Health have identified more than 200 close contacts of the only confirmed monkeypox case in the U.S.—most of whom are health care workers—and that some of those contacts have been vaccinated with doses from the national stockpile.

That stockpile also contains doses of a different, older smallpox vaccine, which has not been reviewed or approved by the FDA specifically for monkeypox, but could also be used to protect people against the latter disease, since the viruses are related and the shots can generate immunity that can cross react with both viruses. This vaccine, called ACAM2000, has been approved in the U.S., Australia, and Singapore to protect against smallpox but can cause side effects including inflammation of heart tissues, and it is not recommended for people with weakened immune systems. Unlike Jynneos, ACAM2000 is built around a disabled monkeypox virus that is still able to replicate, although it can’t cause disease. Jynneos was developed specifically to offer those with compromised immune systems an option for getting vaccinated against smallpox, but its safer profile led the FDA to approve it for the general population as well. The vaccine’s ability to cross-react and generate immune protection against monkeypox made it doubly useful. “It’s important to know that Jynneos can be given to people without needing a detailed health screening,” says Freedman.

There isn’t strong enough evidence yet to suggest where and how the recent outbreaks began, but the clusters in Europe involve men who have sex with men, and “many of these global reports of monkeypox cases are occurring within sexual networks,” said Dr. Inger Damon, a poxvirus expert with the CDC, in a statement on the agency’s website.

The first genetic analysis of the monkeypox viruses from the recent cases suggests that they originated in Nigeria, where one of two common versions of the virus are endemic, and were brought to other parts of the world via infected travelers. But researchers will continue to analyze the genetic data further to understand if and how the latest clusters of cases are related.

In the meantime, should the outbreak grow significantly in scale and scope enough to warrant immunization, health experts in the U.S. are confident that there will be enough doses of the shot to be distributed to Americans who might need them.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com