This story first appeared in TIME’s Leadership Brief newsletter on May 1. To receive weekly emails of conversations with the world’s top CEOs and business decisionmakers, click here.

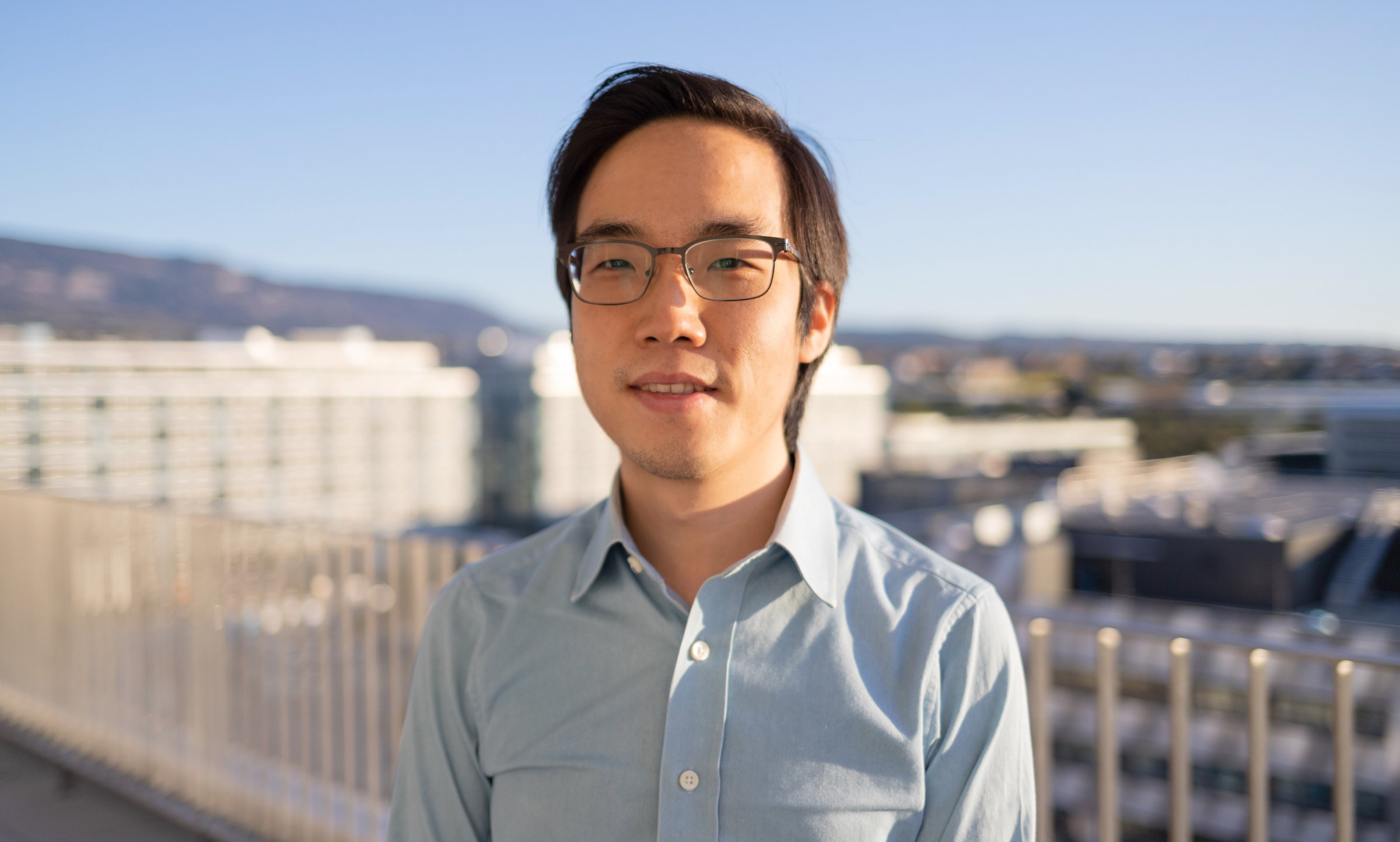

Andy Yen is the founder and CEO of Proton, the company behind the encrypted email service ProtonMail and a suite of other privacy-focused products that are threatening to turn the data-centric Big Tech industry on its head. Proton’s VPN service is currently one of the most-used privacy tools in Russia, helping millions of Russians evade Kremlin censorship amid the war in Ukraine. Here, in an extended interview excerpt from a profile published earlier this month in TIME, staff writer Billy Perrigo speaks with Yen about the rise of encrypted tech and what it means for the antitrust fight against the likes of Google and Facebook, and the future of the internet.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

For the average user, who might not be extremely clear on what the difference is between ProtonMail and Gmail, can you explain how ProtonMail is different?

Google is an advertising company, fundamentally. You like to think that you’re Google’s customer, but you’re not really Google’s customer. What you are is the product that it is selling to its actual customers, which are the advertisers. Proton is a different model. Because our customers are the users, and we are here to serve the users.

The challenge that Google will always have is because they’re essentially selling information about you to advertisers, they’re incentivized to essentially violate your privacy to the largest extent permissible by law and by user tolerance in order to extract the most value from your data. Our model is actually to protect your privacy as much as possible, because that is the reason why our customers are paying us. And I think that direct relationship allows for a much better alignment of interests between us as a business and what our customers actually want.

Read More: Proton’s CEO Wanted to Fight Dictatorships. Now He’s Fighting Big Tech Too

There have been several recent high profile incidents of web services being hacked. And one school of thought is that Google has teams of thousands of cybersecurity hands, and they can patch a vulnerability quickly after it is found. They have the capacity to act much more quickly than a smaller company like yours. Does that make them more secure?

The best way to protect data is actually to not have it in the first place. So if we don’t have access to user data, if we’re not collecting and categorizing your most sensitive information, it’s not actually possible for an attacker to steal from Proton something that we do not possess. So a very good angle of protection is privacy first. Because that’s structurally just safer. And using end-to-end encryption everywhere helps with that.

I don’t think security is a function of how big a company is, or how much money you have. Security is really your culture, your ethics, the way in which you build software. And what you put first. What many people maybe don’t understand is that privacy and security are actually two sides of the same coin. If you build something that is inherently private, it also tends to be more secure.

You’re from Taiwan. Can you explain how that influenced your approach to leading Proton?

Coming from Taiwan, you are, in many ways, on the frontlines of the battle between democracy and freedom. In Hong Kong, which is culturally and geographically very close, we saw how, within a very short period of time any semblance of freedom of speech, privacy, disappeared, right. And you saw that once you lost privacy, when you lost freedom of speech, you lost democracy, you lost freedom. So of course being from Taiwan does inform your worldview and your opinion, and I think the reason I created Proton, and the reason that I’m very deeply committed to our mission, is because there is a direct link between what we do and what I see, as ensuring that democracy and freedom can survive in the 21st century.

(For coverage of the future of work, visit TIME.com/charter and sign up for the free Charter newsletter.)

Proton recently lent its support to two antitrust bills in the U.S. Congress. Can you explain why?

For a long time, people looked at antitrust and privacy as separate issues. And what is becoming more and more clear is that these are actually one issue. Today, if you go out and ask the average consumer, do they trust Google? Do they trust Facebook? Do they feel that their data is being adequately secured? Do they feel like they’re given the right amount of privacy online? The answer is no. People always want more security and privacy. One of the reasons privacy doesn’t really exist much online today is because there’s no competition. It doesn’t really matter how many privacy scandals Facebook has, right? At the end of the day, where else are you going to go? Who else are you going to get your services from? The FTC argued very strongly and correctly, in my mind, that once there was a lack of competition in this space, once Facebook had properly bought up all its competitors, it no longer needed to put emphasis on privacy, because it didn’t matter.

What we know is, when there’s more competition, the consumers always win. And I think if we’re able to get more competition within the tech space, consumers around the world will see increased privacy, because all of a sudden, by making it easier for companies like Proton to compete on a level playing field with Google and other companies, Google will have to respond and provide more privacy in order to stay competitive.

So I want to turn to Russia and the global instability that we’re witnessing. What role do you see your products playing in cases like the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but also the mass protests in Hong Kong?

So in Russia, we have seen a 1,000% increase in the number of Proton VPN users. But Russia is not an isolated instance. It’s not even that unique. f you zoom out and look at just the past 12 months, Russia is probably one of maybe two dozen instances around the world. We have seen a big demand of Proton VPN and ProtonMail, because these are the services that enable a free flow of information. Today, if you want to find the truth in Russia, you need to use a VPN. If you want to communicate securely, you probably have to use a service like ProtonMail. And that’s just the reality. I think what this is really a reflection of is that today, if you look at the global population as a whole, 70% of the people alive on Earth today actually live in a dictatorship. That’s a mind boggling statistic that has actually increased quite a bit over the past couple of decades. I think the development, the proliferation, and also the widespread accessibility of services like Proton, with the values that we are promoting and helping to defend in an increasingly digitized world, is going to be the key towards reversing that trend.

There’s been a lot of talk online recently about this new vision for the Internet with web3. What do you make of that? And to what extent do you see that as a viable vision for the future of the Internet?

I look at it from a scientific standpoint. You do a lot of experiments. They don’t always succeed. Is that the model of the future? Is that going to work? Too early to tell. But just because it exists doesn’t mean it’s going to succeed. The web is full of examples of things that we thought were going to be the future of the internet that turned out not to be the future of the internet.

The way that I think you should view the future is coming back to fundamental problems and fundamental needs, and if these solutions are the best way of solving them or not. If I look at Proton, for example, the fundamental need that we’re solving is privacy. And is privacy a fundamental need? Well, I think it is, I think it’s part of being human.

So can I assume that you’re not going to be integrating blockchain into any of your projects anytime soon?

Well, we would only do it if it is the best way to solve the actual user need. And what I have seen in a lot of blockchain projects is that often it’s not the best way to solve the actual user need.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Billy Perrigo/Geneva at billy.perrigo@time.com