Crypto markets are in freefall this month—and their struggles have been gravely exacerbated by the demise of a $60 billion project that critics are calling a Ponzi scheme.

The project in question is TerraUSD (UST), a stablecoin pegged to the U.S. dollar that its supporters hoped would upend traditional payment systems across the world. But it was wiped out in the span of days when investors panicked and tried to pull out their money, causing a vicious, self-enforcing bank run. The crash bankrupted many investors and pulled down the entire crypto market with it: over $400 billion in value was wiped out in terms of crypto market capitalization.

“This is among the most painful weeks in crypto history & one we’ll reckon with for a long time to come,” Jake Chervinsky, the head of policy at the DC-based lobbying firm Blockchain Association, wrote on Twitter.

While Terra investors were the ones most immediately hurt, its downfall could have both short-term and long-term ripple effects for crypto and beyond, especially as skeptical legislators and regulators survey the damage. “People have lost their life savings through crypto investments, and there aren’t enough protections in place to safeguard consumers from these risks,” Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren wrote in a statement to TIME. “We need stronger rules and stronger enforcement to regulate this highly volatile industry.”

Here’s what happened, and what lies in store following the debacle.

What happened, exactly?

Terra’s rapid rise and fall can be difficult to explain succinctly without any prior knowledge of the blockchain. In fact, many of its boosters hid behind obfuscation and jargon to rebut some of its obvious flaws. Here’s a brief explanation.

Terra is its own blockchain, just like Bitcoin or Ethereum. Its foremost product is the UST stablecoin, which is pegged to the U.S. dollar. Stablecoins are used by crypto traders as safe havens for when markets in DeFi (decentralized finance) get choppy: instead of converting their more volatile assets into hard cash, which can be expensive and trigger tax implications, traders simply trade them for stablecoins.

Some stablecoins derive their value from being fully backed by reserves: if investors decide they ever want out, the stablecoin’s foundation should theoretically have enough cash on hand to repay all of them at once. UST, on the other hand, is an algorithmic stablecoin, which relies upon code, constant market activity, and sheer belief in order to keep its peg to the dollar. UST’s peg was also theoretically propped up by its algorithmic link to Terra’s base currency, Luna.

For the last six months, investors have been buying UST for one main reason: to profit off a borrowing and lending platform called Anchor, which offered a 20% yield to anyone who bought UST and lent it to the protocol. When this opportunity was announced, many critics immediately likened it to a Ponzi scheme, saying it would be mathematically impossible for Terra to give such a high return to all of their investors. Terra team members even acknowledged that this was the case—but likened the rate to a marketing spend to raise awareness, in the same way that Uber and Lyft offered severely discounted rides at the beginning of their existence.

But some blockchain experts say that last week, wealthy investors pulled off a maneuver in which they borrowed huge amounts of Bitcoin to buy UST, with the intention of making huge profits when the value of UST fell, otherwise known as short-selling.

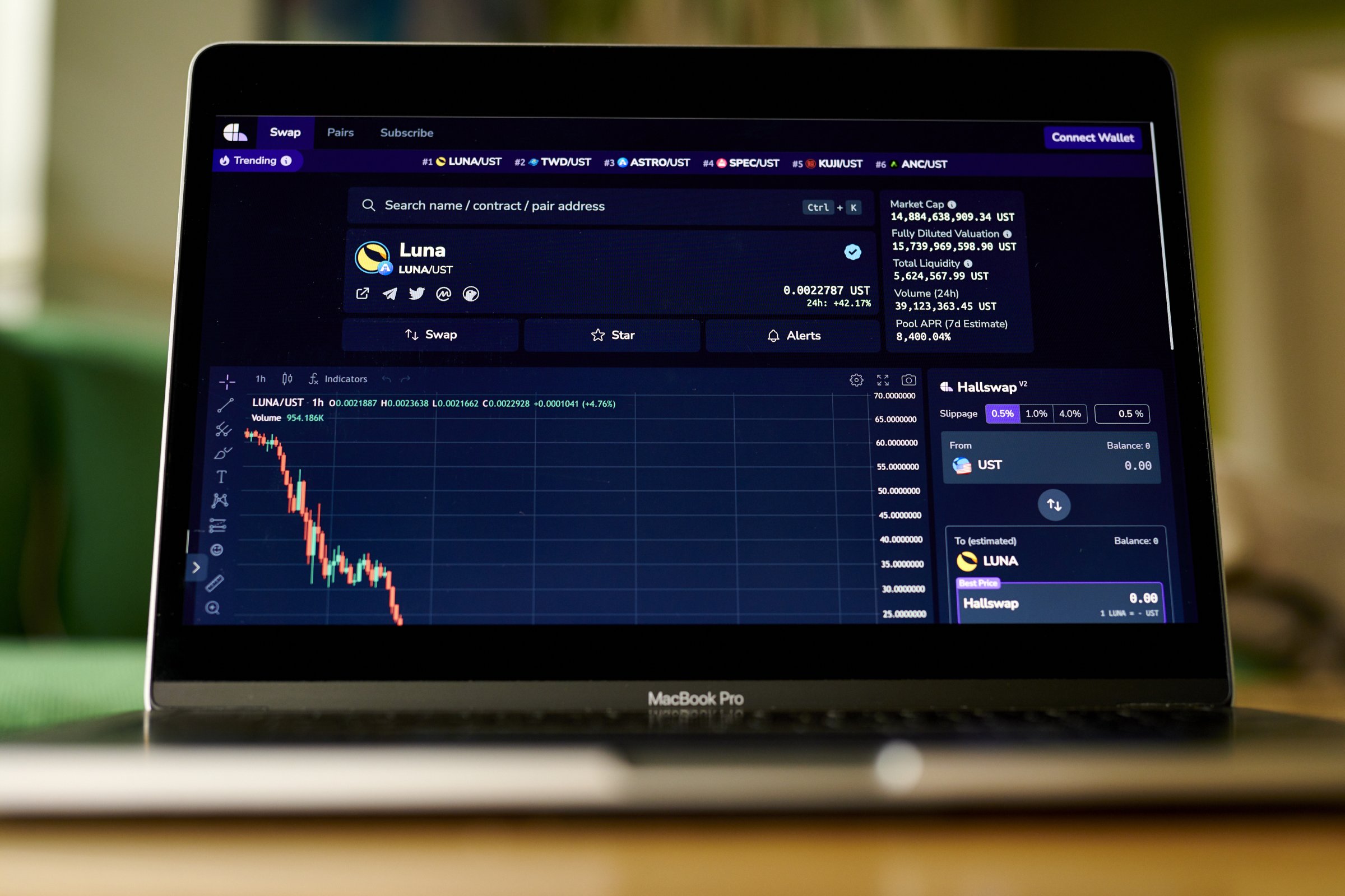

This caused UST to depeg from the dollar. A bank run ensued, with investors who had earned interest via Anchor scrambling to get out the door before it was too late. Their activity caused the linked currency Luna to also crash in what is known as a “death spiral.” As of now, UST is worth 12 cents, and Luna is worth fractions of a penny after being worth as much as $116 in April.

The life savings of many Terra and Luna investors vanished in a matter of days. The r/Terraluna subreddit filled with people opening up about their mental health issues and contemplating suicide. “I’m going through some of the darkest, most severe mental pain of my life. It still doesn’t seem real that I lost $180,000,” one poster wrote.

Terra dragged down Bitcoin and the whole crypto market

Before Terra’s crash, cryptocurrency values were already on the decline, due in part to the Federal Reserve raising its interest rates. (They did so to stop inflation, which has caused people to spend less money.)

But UST’s crash put another dent in the overall market, most centrally because Terra creator Do Kwon had bought billions worth in Bitcoin as a safeguard for UST. When he and the Luna Foundation Guard deployed more than $3 billion to defend the peg, in doing so he caused downward pressure on the market, causing other large investors to sell off their Bitcoin shares. Bitcoin hit its lowest point since December 2020, and Kwon’s ploy to save UST was unsuccessful.

“The way these algorithmic stablecoins are designed, they have this upward force during bull markets, which is how they get so popular,” says Sam MacPherson, an engineer at MakerDAO and the co-founder of the software design company Bellwood Studios. “But the same forces act in reverse during bear markets and expose their fundamental flaws. So that is eventually what triggered [the crash].”

The ripple effects were felt throughout the crypto ecosystem. Because firms sold around $30,000 of Ether in their own attempt to defend UST’s peg, Ether also plunged below $2000 for the first time since July 2021. As many investors tried to cash out their Ethereum-based stablecoins, their sheer number of transactions caused Ethereum’s transaction fees to spike, causing people to forfeit even more money.

Coinbase, one of the crypto world’s biggest and most mainstream companies, slumped 35% last week. And the NFT ecosystem plunged 50% over the last seven days by sales volume, according to Cryptoslam.

The cumulative effect was the loss of hundreds of billions of dollars across the ecosystem. Many worry that Terra’s crash is the first domino precipitating a long-foretold “crypto winter,” in which mainstream investors lose interest and values remain low for months.“ I suspect some cryptocurrencies will be worthless and that capital investment in the space will slow to a crawl as investors nurse their losses, much as we saw in the Internet bubble,” Bloomberg’s Edward Harrison wrote.

So, what could happen next as a result of the crash?

Regulations could tighten

Stablecoins have long been drawing the scrutiny of regulators. Congress held a hearing weighing their risks and benefits in December. The same month, President Biden’s working group called for “urgent” action to regulate them.

Terra’s crash gives even more ammo to regulators who argue that the space needs to be roped under government control. On May 12, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen called for “comprehensive” regulations of stablecoins, saying that while the current crash is too small to threaten the whole financial system, stablecoins are “growing very rapidly. They present the same kinds of risks that we have known for centuries in connection with bank runs.”

Hilary Allen, a professor at American University Washington College of Law who testified about the risks of stablecoins at the congressional hearing in December, says that the fallout of the Terra crash gives us a glimpse of what could be in store should crypto move toward the mainstream without regulation. “In a few years time, something like this could have many more pathways to cause broader harm, especially if the banks continue to get closer to this space,” she says. “I think it’s critical that regulators and policymakers see this moment as a time to put up whatever firewall they can between the traditional financial system and DeFi.”

Massachusetts Representative Jake Auchincloss tells TIME that he’s in the process of drafting legislation requiring stablecoins to be federally audited. Auchincloss doesn’t seek to ban stablecoins, as he believes they could play a role in “keeping the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency.” But he hopes to bring stablecoins under the purview of a federal bureau like the Comptroller of the Currency; to make sure stablecoin issuers can prove they have 90 days of liquid reserves; and to explore the idea of mandating that they provide insurance for customers. “We’re going to let private sector actors make their own risk-reward decisions, and we’re going to empower the federal government to ensure that there’s no systemic risk forming from the sector,” he says.

Senator Warren has been one of the most vocal public detractors of crypto, and took Terra’s collapse as evidence for why regulators need to “clamp down” on stablecoins and DeFi “before it is too late.” Across the Atlantic, the European Commission is considering implementing a hard cap on the daily activity of large stablecoins, according to Coindesk.

Much of the crypto world, meanwhile, seems to have become resigned to the reality of incoming regulation. “A lot of lives have been ruined. The rest of the crypto ecosystem needs to be open to working with regulators such that we can deter these types of situations from happening in the future,” MacPherson says.

Boundary-pushing stablecoins might be over

For many years now, ambitious blockchain developers have embarked upon the quest of creating a functional and safe algorithmic stablecoin, in the hopes that they might be more resistant to inflation than reserve-backed stablecoins and less susceptible to governmental oversight or seizure. But all of them eventually lost their peg and failed. UST, for a few months, was the medium’s crowning success story—and now is its biggest failure.

Its crushing defeat will cast a long shadow over any developer that tries it next: venture capital firms and investors will likely be much more leery of jumping into similar models. Two other boundary-pushing stablecoins, Frax and magic internet money (MIM), saw massive drops in their market caps last week despite holding their peg to the dollar.

“I think this has rightly destroyed any faith in the algorithmic stablecoin model,” Allen says. “It’s quite possible after Terra, we might never see them again—although I never say never when it comes to crypto.”

Over the last week, many leaders in the crypto community have scrambled to distance UST from other types of stablecoins, arguing that reserve-backed stablecoins are comparatively secure and should be allowed to continue to flourish with minimal regulation. Chervinsky, at the Blockchain Association, wrote on Twitter that UST was “in a category of its own,” compared to other models that are “very stable and reliable.” Matt Maximo, a researcher at the crypto investor Grayscale Investments, wrote to TIME in an email that UST’s crash could lead to more demand for dollar-backed or overcollateralized stablecoins.

Allen, however, argues that reserve-backed stablecoins still carry risk. “The best analogy with these reserve stablecoins is with money market mutual funds,” she says, referring to a type of fund whose failure helped trigger the 2008 financial crisis. “And those have had runs and have been bailed out.” (The economics journalist Jacob Goldstein made the same comparison in TIME’s Future of Money issue in October.)

Venture capital may stop pouring money into crypto

Over the past couple years, an astonishing amount of money has flown into the crypto space via venture capital firms, perhaps most notably from Andreessen Horowitz. Terra itself was the beneficiary of a slew of brand-name investors, including Pantera Capital and Delphi Digital.

UST’s crash could raise mistrust on both sides. “It is likely that many of the institutions that have invested in the space may see significant short-term losses, resulting in a slowdown in venture investing,” Maximo writes to TIME. Chris McCann and Edith Yeung, general partners at the crypto-focused VC firm Race Capital, told Bloomberg this week that they had heard of deals falling apart, being repriced, or even founders getting “ghosted” by potential investors.

MacPherson, on the other hand, turned the blame for Terra’s crash in part onto the VC firms that lent their institutional trust to the perilous project. “I think they should take some responsibility with how they’ve ruined some of these regular folks who invested in UST not knowing the de-peg risk,” he says. “Some of the [firms] made a lot of money off this, and I think they should compensate those who have lost.”

At the moment, Terra’s major investors are being forced to decide whether to help bail the project out or cut and run. Many of them have been awfully quiet over the last week. Michael Novogratz, the billionaire founder and CEO of Galaxy Digital who got a giant Luna shoulder tattoo in January, has not tweeted since May 8.

A representative for Lightspeed Venture Partners, a major crypto-focused firm that invested $250,000 in the Luna token, wrote that they remained committed to the space. “Lightspeed has been investing in blockchain for over 8 years. We see this as a computing paradigm shift that is bigger than the ebb and flow of the short term price of Bitcoin. We are doubling down, specifically in infrastructure, DeFi and emerging use cases,” they wrote.

The hype over decentralized finance may be slowing

Much of the promise of crypto lies in its decentralized nature: that its value doesn’t derive from manipulable controlling authority like a bank or a government, but rather sleekly-designed code and network effects. This week, some crypto enthusiasts have argued that Terra’s crash was a successful stress test for this hypothesis: that Bitcoin’s perseverance amid such a giant sell-off proves its durability.

But Terra’s crash did reveal many centralized pressure points in the ecosystem, which, if they didn’t break, at least bent significantly. While there’s no CEO of crypto, one charismatic founder—Terra’s Do Kwon—was able to single handedly create a project that then erased hundreds of billions of dollars in value. He then used his position of power to defend his coin in the same way that the Federal Reserve might, in turn crushing the entire market. Kwon did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The attack showed the vulnerability of Curve pools—decentralized exchanges in which prices can shift quickly due to whales exiting or entering them—and Binance, the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange, which did not have deep enough liquidity to sustain the massive amounts of UST entering circulation.

In fact, the Terra saga shows that blockchain’s decentralized nature allows bad actors to have an outsized impact on the system. But many enthusiasts say that events like this actually help weed out those trying to take advantage of the system, and will lead to a more robust and more educated user base going forward. “The permissionless nature of the blockchain means that we can’t prevent it,” MacPherson says. “But I think we should do a better job of informing the public what the risks are.”

Ponzi schemes might find fewer takers… or not

Whether the debacle sticks in people’s minds as a learning experience is another question entirely. On Thursday, the controversial crypto entrepreneur Justin Sun announced an algorithmic stablecoin with 40% APR for lenders. Galois Capital, in a snarky response, tweeted: “This industry being a self-regulating one requires that learning happen. The results were mixed.” It seems that there are still plenty of crypto investors who will accept extremely high risk, so long as the prospect of extremely high riches remains.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com