Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. looks set to win the Philippines presidential election, according to the Associated Press. A win would mark the return of the Marcos family to power, more than three decades after being forced to flee the country amid a popular uprising following brutal, dictatorial rule.

The victory would also be the culmination of the family’s methodical work to rehabilitate its image. Bongbong Marcos’ namesake and father, Ferdinand Marcos Sr., was president of the Philippines from 1965-1986, and TIME covered the rise and fall of the family’s rule over the country over two decades.

Read more: A Dictator’s Son Rewrites History on TikTok in His Bid to Become the Philippines’ Next President

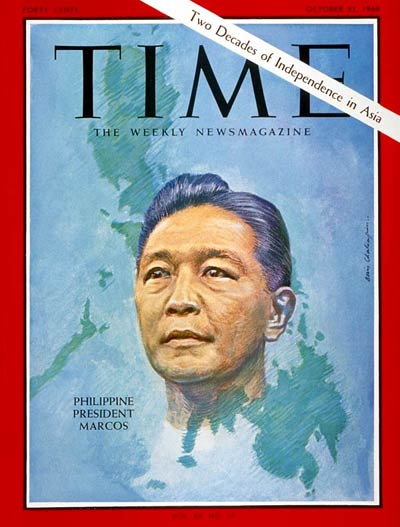

When the elder Marcos was elected in December 1965, after 48 years of American occupation and two decades of independence, TIME called the Philippines “Asia’s freest democracy” and profiled the leader about a year into the job in the Oct. 21, 1966, issue.

“As the sixth President of the Philippine Republic, Ferdinand Edralin Marcos, 49, has been in office only ten months, but in that time he has taken significant steps toward providing the Philippines with the dynamic, selfless leadership it needs to cope with the Southeast Asian burdens of poverty, lawlessness, Communist insurgency and—most important—the quest for national identity after centuries of colonial occupation,” TIME reported. “With his unmatched war record, his dazzling political success, and his stern insistence on an Asian solution to Asian problems, Marcos—with luck—could meet that need. ‘It’s all there,’ says a Washington admirer. Whether the full potential is ever realized depends on Marcos.”

The glowing accolades proved misplaced, however. Marcos’ tenure eventually amounted to “two decades of corrupt rule,” as TIME put it in 2001. He invoked martial law in 1972 for the first time in the country’s history, following an unsuccessful assassination attempt on one of his chief aides. Two years later, he spoke to the magazine, and TIME’s Hong Kong bureau chief, Roy Rowan, wrote that Marcos started off the interview by declaring: “’Never make a big decision when you’re angry, hungry or happy.’”

Martial law lasted until 1981, and during this period, TIME chronicled how authorities arrested thousands of students, journalists, labor leaders and politicians, and the government shuttered news outlets. Marcos’s enemies faced detention, torture, and murder. His family went years without paying taxes and was estimated to have amassed billions of dollars, some siphoned from treasury funds and kept in offshore Swiss bank accounts. First Lady Imelda Marcos made headlines with her lavish lifestyle and collections of 888 handbags, 15 mink coats, and 1,060 pairs of shoes—hundreds of which are on display at a museum in Metro Manila. When TIME asked Imelda how rich she was in 2006, she replied, “If you know how rich you are, my dear, then you’re not really rich.”

Read more: How Philippine Presidential Elections Became All About the Entertainment Factor

Marcos was ousted from power during a democratic revolution in 1986, and he was replaced by Corazon Aquino, the widow of Benigno Aquino, Marcos’s chief political rival. She was named TIME’s Person of the Year for 1986. “Whatever else happens in her rule,” said TIME, “she has also resuscitated [the Philippines’] sense of identity and pride.” Ferdinand Marcos Sr. died three years later in exile in Hawaii, passing away on Sep. 28, 1989, at the age of 72. “He died his country’s greatest villain,” TIME wrote in his obituary, published in the Oct. 9, 1989 issue.

Marcos Jr. was able to secure a historic 33-point lead in pre-election polls ahead of the election by recasting his father’s dictatorial rule as a golden age for the Philippines. He skipped debates and gave few interviews. He emphasized unity in his campaign, but was light on policy details, TIME’s Chad de Guzman reported from Manila.

In unofficial election results Tuesday, Marcos had nearly 30.8 million votes, according to the AP. That is more than double the votes of his closest rival, Vice President Leni Robredo.

Politics watchers told TIME recently that they think Marcos Jr. will be a different kind of leader from his father. As Richard Heydarian, a Manila-based professor of political science, put it, “I doubt the Philippines will move towards a 20th century-style dictatorship. I think that is kind of passé.” However, only time will tell; his father’s tenure began with similar hopes.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com