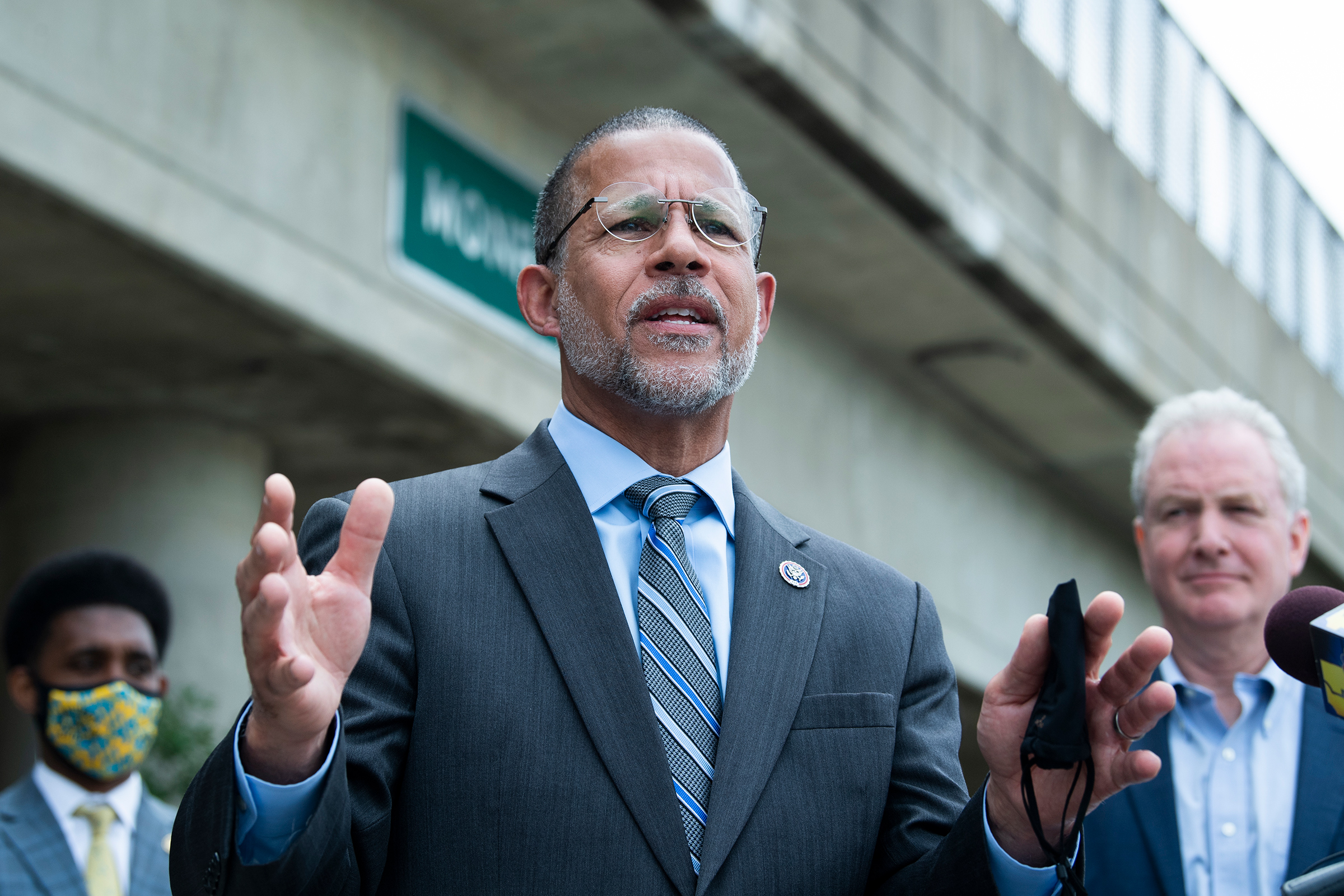

Rep. Anthony Brown, Democrat of Maryland, wants to be the state’s top law enforcement officer, but his own campaign’s spending may violate state election law, according to campaign finance experts.

The three-term congressman announced on Oct. 25 that he would retire from Congress and run for Maryland attorney general. Since then, he has used funds from his Congressional campaign account to bankroll his bid for statewide office, a TIME review of his financial disclosures shows.

Brown’s Congressional campaign spent as much as $40,000 supporting his campaign for attorney general between November 2021 and March 2022, the TIME review found. The biggest ticket item was more than $24,000 for the salary for his state campaign’s finance director, according to Brown’s most recent filings with the Federal Election Commission. Meanwhile, Brown spent nothing from his state account’s war chest to compensate the campaign’s staff in its first months of operation, the TIME review found.

That may be illegal. Maryland’s election laws set a contribution limit to state campaign committees of $6,000 per election cycle. The payments from Brown’s federal campaign committee to support his attorney general race may have exceeded the legal contribution limit by as much as $34,000 over the last five months, the campaign finance experts say.

“This is a credible violation, since it’s clearly, under the law, a contribution,” says Ann Ravel, former chair of the FEC during the Obama years and now a lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley’s School of Law, referring to the federal committee’s expenditures.

The salary payments are a particular problem. “In payroll, you’ve got to stay current,” says Michael Toner, former chair of the FEC during the Bush administration. “If the fundraising person is being paid by the federal campaign committee during a period when the congressman has announced he’s not running for another term—he’s running for attorney general—that creates a pretty strong inference that that’s subsidizing the attorney general race.”

Brown himself declined to answer questions for this article. His campaign denies any wrongdoing. They say Brown’s federal election funds have been spent on the six-month process of “winding down” his congressional campaign, not supporting his state attorney general race. “All federal expenditures have been made as a part of Congressman Brown’s official duties, as well as the costs of winding down the office,” Dylan Liau Arant, Brown’s state campaign manager, tells TIME. The finance director had been working “split time” for the state campaign, for which he will later be reimbursed, and his compensation from the congressional campaign, where he has also served as finance director since 2019, will stop soon, Liau Arant says.

Such double hatting is common, but operatives who work for both a federal and a state campaign simultaneously are normally compensated by both entities, according to Maryland election experts. Brown’s state attorney general campaign has paid $0 toward the finance director’s salary since last October, according to his most recent state campaign finance disclosures. Over that period, that same operative helped raise more than $600,000 for Brown’s state attorney general campaign.

Maryland’s Democratic primary for attorney general is among the most competitive in years. Brown, a Harvard Law School graduate, was former Gov. Martin O’Malley’s lieutenant from 2007 to 2015. He is now running against O’Malley’s wife, Katie Curran O’Malley, who served as a Baltimore City Circuit Court judge until she announced her bid for attorney general last year. Her father, Joe Curran, was Maryland attorney general from 1987 to 2007.

The campaign is set to intensify as the July 19 primary election day approaches. Early polling, from November, showed Brown with a two to one lead over Curran O’Malley. Maryland hasn’t elected a Republican to the office since 1919, making the primary especially important.

Annapolis political analysts believe that Brown’s campaign spending woes could throw a wrench into the race. “If you’re running to be the chief law enforcement officer of the state of Maryland, you cannot have legal or financial questions regarding your campaign,” says John Dedie, a political science professor at the Community College of Baltimore County. “It’s a bad look.”

It’s not clear why Brown, 61, would use his Congressional campaign money on his attorney general campaign, rather than the more than $600,000 in his state account at his disposal. But a review of Brown’s political career shows this isn’t the first time his campaign finance practices have invited scrutiny.

A rocky history of funding campaigns

In 2014, Anthony Brown was considered heir apparent to the Maryland governorship. He’d served as lieutenant governor for eight years, and both Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton held fundraisers and rallies for him. In a state where Democrats outnumber Republicans two to one, FiveThirtyEight declared him a 94% favorite.

But a vigorously mounted campaign from a little-known real estate executive, Larry Hogan, took Brown by surprise. Hogan had been pillorying the O’Malley-Brown administration for raising taxes, and the political upstart took aim at Brown’s management of the botched rollout of the state’s new healthcare exchange under the Affordable Care Act. In June 2014, Brown was leading Hogan in the polls by 18 points. Come October, Brown’s lead had shrunk to nine points.

With his political fortunes at stake, Brown authorized his campaign to take a $500,000 loan from the Laborers International Union, which had endorsed him; the money would go toward television advertising, direct mail, and payroll for staff. Brown’s team planned to pay it back with a surge of campaign donations in the final days of the election. “We will not have any debt after the election,” his campaign manager at the time told The Baltimore Sun.

But in November, Brown lost the election to Hogan by five points, and was left holding the bag on that $500,000 debt. A former Army lieutenant colonel, Brown had signed a personal guarantee for the loan’s repayment and was personally liable for it, according to The Sun. His state campaign account didn’t have enough leftover cash on hand to pay off the whole debt.

Brown’s political prospects improved the following year. In March 2015, Brown announced his candidacy for one of Maryland’s open U.S. House seats. Over the course of the race, Brown lent his Congressional campaign a little under $400,000 from his personal holdings. This time, Brown won and contributions flooded in. His campaign was able to reimburse him for his personal loan.

But Brown’s state campaign account was still in the red. So Brown again made a personal loan to his campaign, helping it to finally repay the union in January 2018. At that point, his state campaign owed him $275,000, according to The Sun.

For three years, that debt persisted. Brown was a U.S. Congressman; his state campaign account was dormant. Then, this past October, things changed. After Maryland Attorney General Brian Frosh announced that he wouldn’t run for reelection, Brown launched his bid and began raising money for the state account once again. The finance director, who had worked for Brown’s congressional campaign, was given the same title for Brown’s attorney general campaign. Within three months, he helped raise $647,000, with $617,520 cash on hand, according to Brown’s first campaign finance report to the Maryland Board of Elections.

That same filing, however, showed no payments for campaign staff or consultants. Between October 2021 and March 22, the report showed Brown paying $0 in salaries and compensation, and just $280.11 on rent and office supplies. By contrast, when current Maryland Attorney General Frosh was running for the same office eight years ago, he had spent more than $103,000 on salaries at this phase of his campaign, and more than $7,000 on rent and office supplies, according to his January 2014 finance report. Curran O’Malley, for her part, spent $4,000 on salaries and $134.76 on rent and office supplies, according to her latest finance report.

During this same time period between October 2021 and March 22, Brown’s Congressional campaign account spent roughly $40,000 on costs that appear to support his state campaign, including salaries, payroll taxes, workers compensation insurance and other expenses, like cell phone charges and rent at a temporary office space called The Yard, according to his two latest FEC reports. The biggest outlay from Brown’s federal campaign account in support of his state campaign were the salary payments.

Maryland election officials declined to comment on Brown’s finances, but a senior official said payments for services to a campaign are not allowed to exceed the $6,000 limit. “If other entities pay for services provided to a campaign, it is considered an in-kind contribution,” says Jared DeMarinis, director of the candidacy and campaign finance division of Maryland Board of Elections. “In-kind contributions are subject to the contribution limit of $6,000 for the four year election cycle.”

Brown’s campaign manager, Liau Arant, says the salary from the federal committee wasn’t paying for work on the state campaign. The disbursements were for the finance director “performing wind down functions for Anthony Brown for Congress” while he was “working for Friends of Anthony Brown on split time,” Liau Arant says. “The finance director agreed to be paid after the January reporting deadline, which is common practice in both state and federal campaigns to keep the cash on hand number as high as possible and permissible by Maryland and federal campaign finance law.”

Campaign finance experts say that the state account should have then retroactively paid him shortly after the deadline for the three-month period when he helped to raise nearly $650,000. “That’s the norm,” says former FEC chair Ravel. “That’s something that they should have done had they intended to pay with that mechanism.” Failing that, the finance director’s salary should at least have been listed as an outstanding bill on the latest Maryland filing. “Otherwise, it seems like this is all the explanation they came up with once the media started to inquire,” says a former Maryland election official.

Liau Arant, who began working for Brown in January, also disputed that other charges disclosed in Brown’s federal campaign filings were related to the state attorney general campaign. He said the cell phone was “still being used in connection with the Congressman’s official duties and wind down activities” but that “the state account will reimburse the federal account for any use of the cell phone for the Attorney General campaign.”

At the same time, Liau Arant challenged the notion that the Congressional campaign-funded office space was being used for the attorney general bid. “There are separate accounts at The Yard, one for the winding down of the federal campaign and the other for the AG campaign,” Liau Arant said. “These amounts are billed and will be reported, separately.”

Brown’s attorney general campaign began paying for an extra desk in shared office space at The Yard in February and added another one in April, according to invoices provided to TIME by the Brown campaign. But when TIME visited the office paid for by the congressional campaign last week, the finance director, who was using it, said he was working on the attorney general campaign. Asked for a business card, he said he didn’t have any. “I only have ones from the congressional campaign,” he said. “They’re not current.”

The original version of this story misstated the decade in which Maryland last elected a Republican to the office of attorney general. It was the 1910s, not the 1950s.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com