GRAND RAPIDS, MI – In America, always listen for the we.

Not the pluralis majestati, the “royal we” that signifies the power of the elevated person. Not the “we” of American politics, used—or some might say abused—to position a candidate inside some calculated group. This we is the one used to convey kinship, shared values and concerns, joys and pains.

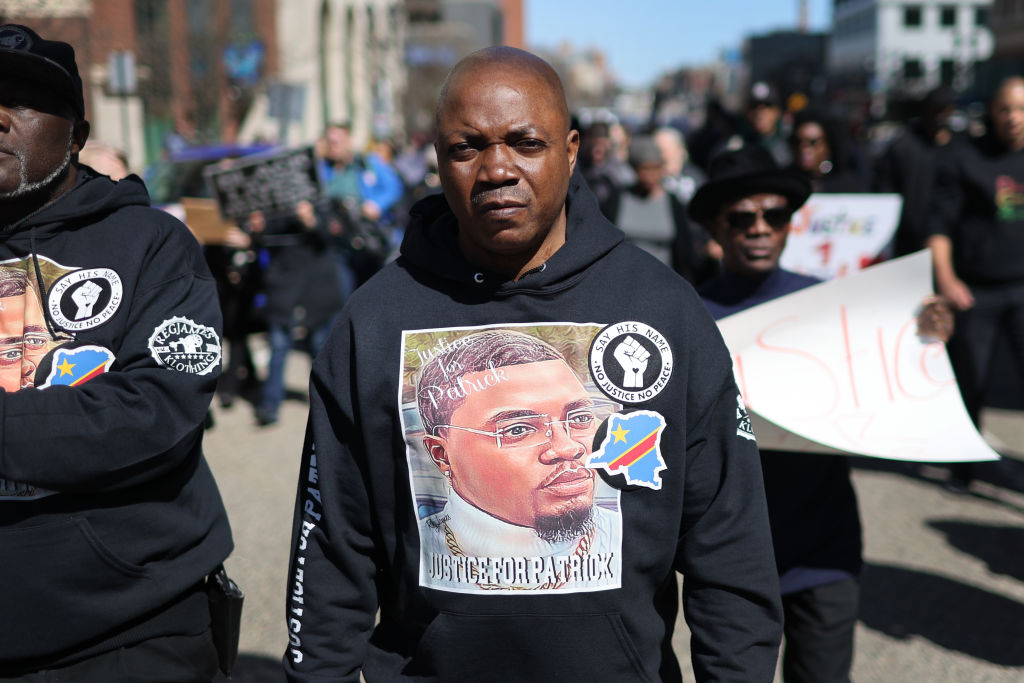

That we signifies connections have been forged, sometimes in fire. It was that we the Rev. Al Sharpton turned to on Friday as he began to preach at the funeral of Patrick Lyoya, a Congolese refugee killed April 4 when a Grand Rapids, Mich., police officer fired a shot into the back of his head.

“They took us from the shores of Africa and brought us across the Atlantic and made us slaves,” Sharpton, who demanded that the officer’s name be released, told those gathered, as a translator echoed him in Swahili. “And they devalued our human worth by teaching their children that we were less than they were…. But I come almost 400 years later to tell you that we were not created to be your boys and girls… And you thought we wouldn’t come from all over the world and let you know that enough is enough?”

It was that we, enunciated inside the Renaissance Church of God in Christ, a predominantly Black American congregation in Grand Rapids, that prompted Delvil Basengezi, another Congolese refugee and a co-worker of the dead man lying in the white casket at the front of the sanctuary, to slowly wave a massive blue, yellow, and red banner—the Democratic Republic of Congo’s flag. If anyone thought it was discordant that Sharpton’s message prompted such a display from someone who measured his history in the United States in years, not centuries, nobody said so. After all, those words marked moments in some ways emblematic of a day in which elements of the Black American and Congolese immigrant experience seemed to mingle. They were a fitting indicator of the burgeoning relationships some have found in Western Michigan in the 18 days since Lyoya was killed.

Read more: What We Know So Far About the Police Shooting in Grand Rapids, Mich.

Of the nearly 200,000 people who call Grand Rapids home, about 18% are Black. (White residents make up a majority of the population here, at 58%, while 16% of those living in Grand Rapids identify as Latino and nearly 3% Asian.) Within that population are more than 1,000 Congolese families, many of whom began settling in the Lansing and Grand Rapids area about 20 years ago, says Freddie Nyembwe, president of the Lansing Congolese Community. Patrick Lyoya lived in Grand Rapids, the major city in nearby Kent County, his family having arrived in the U.S. about six years ago—assured, his father Peter said through a translator, that this was a place where they and their children would be safe. His parents and most of his siblings live in Lansing, about 70 miles away.

Tribal, political and other conflicts that separated people back home in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nyembwe says, can carry over after emigration, creating stubborn divides in the community. “But we are a family. The one who passed away, who got killed, to me I treat him as a Congolese because I don’t think about tribes. I think about my country,” Nyembwe says. And in every country, every civilized nation, he says, justice is an essential element.

To him, that drive for justice is enough to unite people across dividing lines—not just within the immigrant community, but also across the divide between those born in the United States and those born in Africa.

“It’s been a growing relationship,” agrees LaKiya Thompson-Jenkins, executive director of LincUp, a nonprofit organization that has been pushing for police reform in Grand Rapids. “I don’t think things are where they needed to be [in terms of including African immigrants in local conversations about justice] but there has been progress. There has been intentionality in making sure Africans are really represented at the various tables in the city of Grand Rapids.”

The weeks since Lyoya’s death have put a harsh spotlight on that developing relationship. It was on display eight days after Lyoya’s death, in a gray-walled Grand Rapids City Hall meeting chamber, at a time when people in other parts of the country had just begun to hear the name of the 26-year-old auto-parts factory worker whose passions included teaching young people traditional Congolese dance. In Grand Rapids, angry that Lyoya’s mother and father had not been allowed to see his body and that video of the incident had not been made public, people had marched on the city’s streets. On April 12, at the first City Commission meeting since Lyoya’s death, so many came to share their outrage in the three-minute intervals allotted for individual public comments that the meeting stretched to five hours.

Read more: Behind ‘Grand Rapids Nice,’ Police Problems Run Deep in Michigan

Some of those who spoke were themselves African refugees and immigrants. A few were white Americans. Most were Black Americans who spoke about Lyoya’s shooting as part of a larger pattern about which they have long been concerned. traced not by national origin but by skin color.

“This young man came here with dreams of a future,” said a young Black woman with an American accent and a leather jacket who did not give her name, in a statement now preserved on the video record of the meeting. “I am ashamed that this city…brought death to this young man who came here with dreams for a future. You too should be ashamed.”

Grand Rapids Mayor Rosalynn Bliss, who is white, had at the start of the meeting banned applause, describing it as a disruptive time waste, so the room erupted in a low din of snaps and murmurs when the young woman in the leather coat was done. The next speaker, who’d been nodding along vigorously, was Fridah Kanini, a woman with a Kenyan accent who had earlier offered to interpret for Swahili speakers in the room.

“Many of us as refugees and immigrants, we came to America for safety and… you took it away,” she said, detailing how in her experience it has seemed that when police hear African accents, they assume there will be few consequences for violating residents’ rights. “Beyond the racism that we face, we also face other barriers,” she said.

In the past, she added, she has suffered rights violations in silence. If Lyoya had not been killed, she said, he likely would have gone home and done the same. But, she said, that silence ends now.

“Africans, we are people who want peace. We want just to be able to provide for our families, go to school, work hard, become [executives], do the best things we can for this city,” she said. “We are here. We are staying and we need to be factored into everything that you plan to do. …We don’t need to wait for another tragedy to happen so that you can hear us.”

“Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness was the bond given to Mama and Papa Lyoya,” says Bethlehem Kongwa Shekanena, when she rises to speak at the funeral on Friday. A young woman who is the daughter of Congolese refugees, she speaks English with an accent no different than others born in Michigan. She is a first generation American. But like Patrick Lyoya and his parents, she and her family are also members of the Bafuliru tribe, one of more than 400 in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the president of the Bafuliru Tribe in America had earlier explained to mourners. It’s Shekenena’s words that prompt both of Lyoya’s parents to weep. “Like many… including my own family, Mama and Papa Lyoya came to this country with an assurance, a promise that they and their children would not be presented with turmoil and death…The very foundation of what makes America, America—it was broken when Patrick Lyoya was killed in the street.”

Peter Lyoya learned about the death of his eldest son, Patrick, from a phone call, says Israel Siku, the primary interpreter and spokesman for the Lyoya family. Starting then and every day since, all the facts, figures and details he has learned about Patrick’s fate have come at him fast, in his third language—English, which the French and Swahili speaker began acquiring less than a decade ago.

“Imagine,” says Siku. “Imagine that. Imagine what this family is going through.”

In an April 8 radio interview with Kent County Commissioner Robert Womack, who is also the host of a local talk-radio program, the elder Lyoya explained how police called, looking for the father of Patrick Lyoya. Sir, an officer said, your son has been killed.

Before this moment, the idea that the police might target, injure, or kill any of his children was not, for Peter Lyoya, a prominent concern—despite what local activists say about the perception that immigrants often have their rights ignored. Nor were issues with race and policing a frequent topic of conversation inside the family, Siku says. He knows that for some people, Lyoya’s death can be reduced to one simple question: After getting out of his car during the traffic stop, after confirming to the officer that he did speak English, why did he run? But to Peter Lyoya, when he saw the tape, a possible answer came to mind easily. Wouldn’t his son have been—justifiably, it turned out—afraid?

In both of his jobs, Womack, who is Black, hears a lot of stories. He hears about the level of fear that a lot of Black men in the area live with, he says. “Now you have the added element of our African brothers and sisters who, like Patrick Lyoya’s father, believe police are handling them differently—no, dangerously. Peter Lyoya told me he does not believe that the officer would have killed his son like an animal, shot him in the head, if he were not an African.”

After Womack learned that although four days had passed since the fatal shooting, the elder Lyoya had not been allowed to see his son’s body, Womack contacted Ben Crump, the civil rights attorney perhaps best known for his work with the families of Trayvon Martin and George Floyd. (As recently as Friday, Siku says, the family has not heard from state police or the Grand Rapids Police, who did not respond to requests for comment. Michigan State Police issued a statement Friday morning saying that the investigation into Lyoya’s shooting continues and no timeline for its conclusion exists. The name of the officer involved has not yet been released.)

Read more: Inside Ben Crump’s Quest to Raise the Value of Black Life in America

“This is what Patrick[‘s] family firmly believes, especially his father,” Siku tells me several days before the funeral, which was attended by more than 500 people. “[With Patrick] being an African, [officials] thought they will put it under the rug. They thought [the family] will not see any support like this.”

They thought, wrongly, Siku says, that local activists would not care. They thought Black Americans who have long paid close attention to policing in Grand Rapids would not see Lyoya as another loss close to home.

“They were wrong. We are one. We are all African,” he says.

The truth is likely more complicated than that. One indicator: during his homily, Sharpton alleged that more than one church in the area refused to give the Lyoya family a place to mourn, out of fear of crossing the police union and public officials. But in the emotion of Friday’s remembrances, it was possible to believe that unity could be found in strife. There was much that happened at every turn of Friday’s services—in the church and at the graveside—that was both Congolese and Black American. And if there is one thing with which a Black American church has ample practice, it is the management of deep painful emotions that can overflow out of a burdened human being.

As mourners filed past Lyoya’s open casket, a trio of Black American women stood to the side holding boxes of tissues and a basket to throw them away. Throughout the service, Black American women affiliated with the church, dressed in all white, fanned and comforted those who were overcome. A choir of 15 Black American people sang such a rousing rendition of “You Are (The Source of My Strength)” that Lyoya’s mother began to wail. And when two of Lyoya’s friends, young men who are also Congolese refugees, sang a song in Swahili with a Congolese sound over an almost hip-hop beat, other members of the family fell from their seats and had to be collected from the floor. The song had been written by the young men specifically for their dead friend.

At the gravesite, after a brief ceremony and comments from the leader of a local Congolese ministers’ association about the way that justice for Lyoya would ensure that his death was not in vain, a staggering reality—one experienced all too often by Black Americans—became clear.

It is a Congolese tradition for an eldest son like Patrick Lyoya to speak the final words before his father’s body is buried. But, as two police cruisers waited across the street, Peter and Dorcas Layoya had to bury their son.

It is also a Congolese tradition to watch a body be placed permanently in the ground; doing so wards off grave robbers and curses, a woman standing near me explains. So, as Dorcas Lyoya wailed about the pain of leaving her son in the graveyard on a cold rainy day, and mourners sang a song about happiness in heaven in Swahili, two white graveyard workers inserted her son’s casket into a concrete vault and moved it into the gaping grave, a deep pit in the Michigan red brown dirt.

Issues with policing in the United States don’t always rank near the top of refugees’ concerns, Crump tells me before the funeral began. But now the problem has come to them in an urgent way, and in his address to the mourners, Crump emphasizes that they are not alone in their grief.

“Where they shot this young brother in the back of the head,” Crump says during his speech at the funeral, “his Black life mattered. His African life mattered. His human life mattered. This is not just a legal issue. This is not just a civil-rights issue. This is a human-rights issue.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com