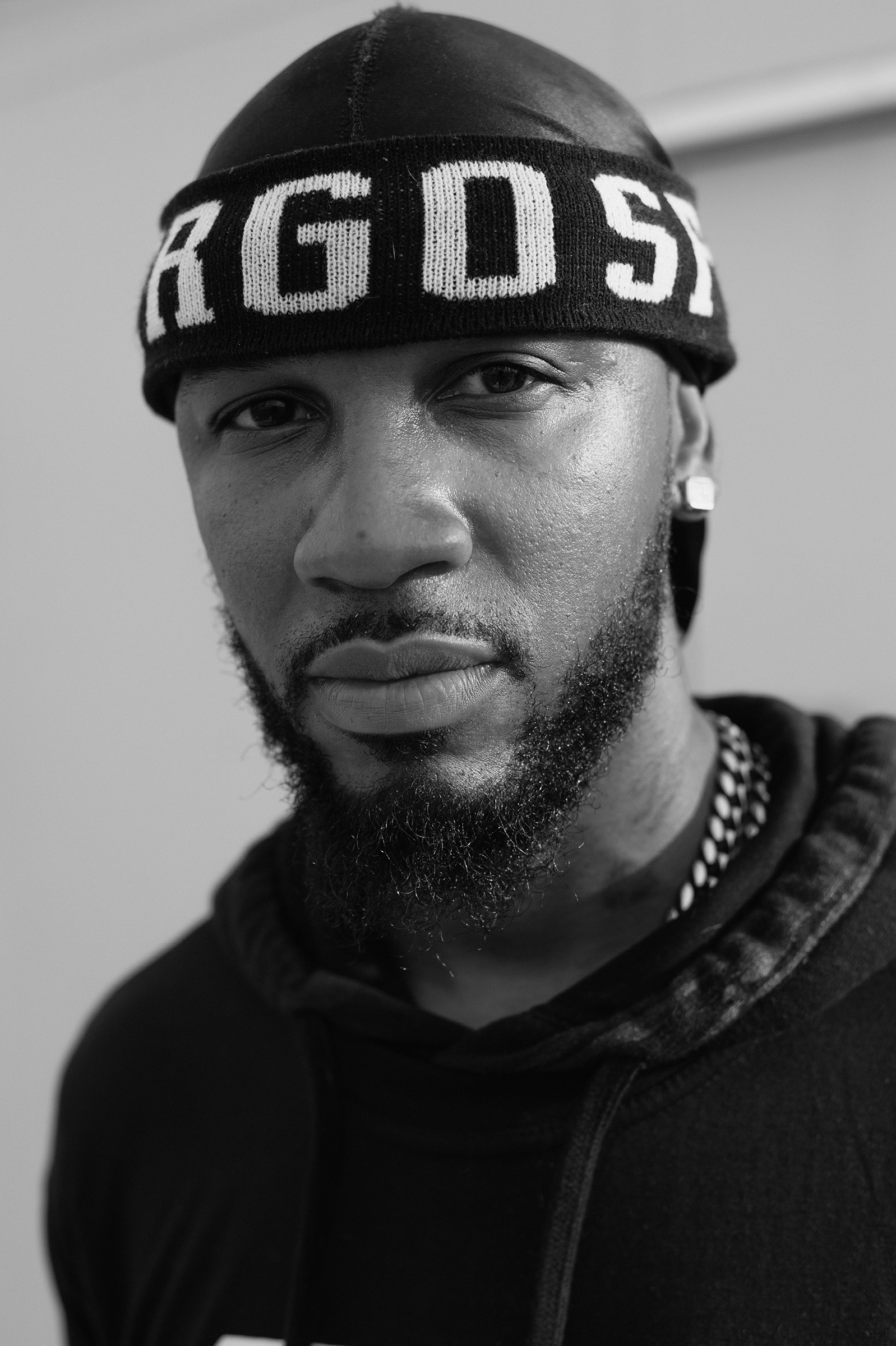

Inside the ground-level Staten Island apartment that serves as the operational headquarters of the Amazon Labor Union, Chris Smalls is spitballing about real estate. Wearing immaculate Air Jordans and boxy sunglasses, surrounded by half-empty pasta boxes and a pot of old mac and cheese, the leader of the first successful union drive in Amazon history is talking with Julian Mitchell-Israel, the ALU’s field director. Maybe, Mitchell-Israel muses, the union’s next headquarters could be in a bodega.

Nah, Smalls says, with the smallest shake of his head. “We’re a big union. Not a bodega union.”

By conventional standards, the Amazon Labor Union—just a year old and less than 10,000 members strong—isn’t actually that big. Not when compared to its long-established unions with hundreds of thousands of members. That’s part of what made its victory over a very big, very powerful, and fiercely anti-union company so audacious.

On April 1, almost exactly two years after Amazon fired him, Smalls, 33, helped the ALU win the vote to unionize at the Staten Island warehouse JFK8, the largest facility serving New York City and the surrounding area. It was the first crack in Amazon’s formerly impenetrable anti-union armor. Smalls and his friend and co-organizer Derrick Palmer did it without any professional organizing experience, without any formal affiliation with established organized labor, and without big money behind them. Their union raised roughly $120,000 on GoFundMe, compared to the $4.3 million Amazon spent trying to beat them.

Until recently, a triumph like this would have been unthinkable. Unionization efforts “never ever win against Amazon, and this was a union that didn’t exist two years ago,” says John Logan, Director of Labor and Employment Studies at San Francisco State University. “No one thought they had a chance.”

But the pandemic exposed glaring inequities that have triggered a new labor reckoning. Starbucks workers across the country have voted to unionize over the past few months, New York delivery drivers are forming a labor coalition, and Apple Store employees in Atlanta just demanded a union for the first time. But the Amazon Labor Union’s victory over one of the world’s most formidable companies is the most significant yet.

Smalls says the triumph was the result of a different way of thinking about labor organizing. “This is the new school,” he says as Mitchell-Israel orders 800 chicken wings to feed Amazon workers on their break. ”Old school” is Big Labor, the existing 20th-century union infrastructure. “The ALU represents the new face, the new-school style of 21st century organizing, ” he adds. “Where younger adults are taking charge and putting workers in the driver’s seat.”

Smalls means “workers” in the specific sense—as in, people employed by Amazon—and not “workers” in the general sense, which is often used as a catchall term in labor circles to mean anyone who isn’t in management. This is just one of the ways that Smalls deviates from the well-worn progressive rhetoric that may energize college-educated liberals but means little to Amazon employees. “We don’t go home and turn on CNN, we don’t go home and turn on Fox,” he says, noting that Amazon workers are often too tired to follow politics. “If I brought AOC and Bernie out here, I would have to inform the workers who they are and what they represent.”

Smalls may be organizing out of a black Chevy Suburban packed with iced tea bottles and rolling papers, but it’s clear that Amazon underestimated his savvy. In a memo that leaked shortly after his firing, Amazon lawyers said that Smalls was “not smart, or articulate.” But Smalls’ understanding of what it’s like to work at Amazon is one reason why he and Palmer succeeded where larger, more powerful unions have failed. Only last year, Amazon beat back a unionization effort driven by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union at a Bessemer, Alabama facility in what was then the biggest labor drive in the company’s history. (The union challenged the decision with the National Labor Relations Board, claiming Amazon illegally interfered in the election. A final result is still pending.)

Read More: How Amazon Won the Union Vote in Alabama

Smalls has an idea of why that effort fell short. “The timing, the approach, the campaign—it was just all wrong from the beginning,” he says of the Bessemer union drive. Alabama’s right-to-work laws presented challenges; the plant was new enough that workers weren’t as disillusioned as at JFK8.

Most importantly? The drive was organized by an “established union, a third party that doesn’t know Amazon,” Smalls says.

“In order to get it done, you gotta build from within,” he adds. “Not from the outside, but from the inside out.”

No one could have predicted that Chris Smalls would be the David to Amazon’s Goliath. Raised by a single mom in Hackensack, New Jersey, he gave little thought to the plight of the working masses growing up. He spent his time playing basketball and football, writing rap songs with his friends and dreaming of becoming a hip-hop artist. Smalls’ mother worked as an administrator at a hospital, and had once been part of SEIU 1199. But Smalls says the union made so little difference in their lives that she “forgot that she was even a part of the rank-and-file at one point,” he says, adding that she hadn’t remembered organizing for a contract. “A co-worker reminded her.”

Smalls gave hip-hop a shot as a career, but when his ex-wife got pregnant with twins, he decided to shelve his music dreams in search of more stable income. After stints at Amazon facilities in New Jersey and Connecticut, Smalls was hired at JFK8 in 2018. He worked as a process assistant, overseeing customer items being picked to be packed and shipped. At first he loved his job. The team was small, and his general manager was Black and seemed invested in helping him and other Black workers advance at the company. “Everybody looked out for one another,” he says.

But over time, that culture changed. The small facility ballooned to thousands of workers, management changed, and what had felt like a workplace full of human beings soon began to feel like a team of “industrial athletes,” as one leaked company memo put it.

“It was all about metrics. It’s not about the person,” Smalls says. “They could care less if that person breaks down.” The work became so physically grueling that after a while “it doesn’t matter what shoes you wear,” he says. “They all become bricks on your feet.”

Smalls’ frustration peaked during the early days of COVID-19. Employees at JFK8 were required to keep working in person even as much of the rest of the city shut down to slow the spread of the virus. Publicly, Amazon said the company was taking “extreme measures” to keep workers safe. But Smalls says that people worked “shoulder to shoulder” inside the facility, and that colleagues were coming to work sick. “Everybody was just worried that this is a life-or-death situation,” he says.

In March 2020, he and Palmer staged a walkout in protest. Later that night, he was fired. (Palmer received a formal warning.) In a statement, Amazon said Smalls was fired for “violating social distancing guidelines.”

Read More: Andy Jassy on Figuring Out What’s Next For Amazon

In response, Smalls and Palmer decided to stage demonstrations to advocate for workers’ rights. They did things like protest outside of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos’ mansions. But when the union drive in Alabama failed, “that’s when we decided to unionize,” Smalls says. “We went down there, we saw something that we thought we could do better.”

They started with a two-pronged approach. Smalls would organize at bus stops outside the facility, offering free food to hungry and exhausted workers. Palmer, who still worked at the company, would work the break room inside. “I used to listen more than anything,” Smalls says, adding that the campaign was more about educating workers and “explaining what a union can provide.”

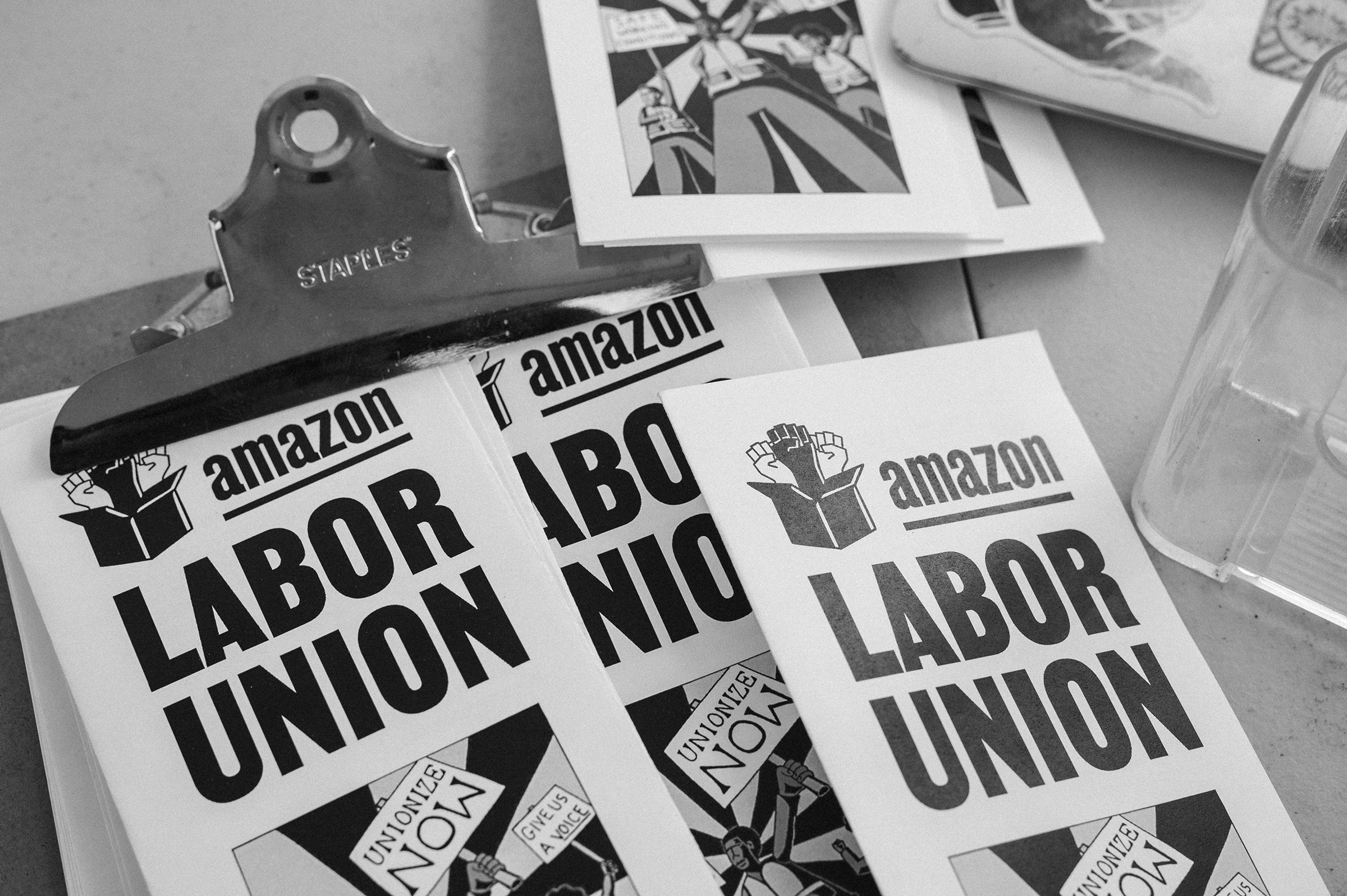

In April 2021 they began to call themselves the Amazon Labor Union. One organizer used TikTok to spotlight the company’s anti-union propaganda, and posted videos of organizers stationed outside the facilities in the freezing cold. The union made a point to emphasize human connection among the workers. Smalls handed out free weed and food along with pamphlets and books, and organizers set up bonfires to keep people warm on breaks.

“We had a compassionate, humanizing, caring type of campaign,” Smalls says. “We played the tortoise and the hare.”

The months dragged on. Bezos traveled to space, thanking Amazon customers and employees because “you guys paid for all this.” (Smalls recalls signing up a lot of people that day.) Some organizers got jobs at Amazon specifically to unionize—a labor strategy known as “salting.” It helped the union stay in touch with workers on the inside. “As organizers, we have to try to be some of the best employees, because otherwise you’ll get fired,” says Justine Medina, a “salt” who joined Amazon to help with the organizing effort.

The tortoise was gaining ground. But Amazon pushed back hard, forcing employees to attend mandatory meetings packed with anti-union rhetoric. They reminded workers that dues would come out of their paychecks, and suggested that unions were third-party interlopers trying to come between workers and their employer. “As a company, we don’t think unions are the best answer for our employees,” Amazon spokeswoman Kelly Nantel told TIME in a statement. “Our focus remains on working directly with our team to continue making Amazon a great place to work.”

But organizers say that the ALU’s approach kneecapped Amazon’s efforts to portray them as outsiders. “As long as we’re putting in the time, we’re putting in the love, we’re making it about building human connections, that message doesn’t resonate with people,” says Mat Cusick, an ALU organizer who works at a delivery facility next to JFK8.

On the day JFK8 voted to unionize, Smalls was thrilled but not surprised. “I knew that we were going to win. I never doubted it,” he says. “That was the best feeling in my life next to my kids’ birth.”

On a blustery April morning, ALU organizers greeted workers coming out for their break at LDJ5, another Amazon facility on Staten Island, which is set to begin voting on unionizing on April 25. The organizers handed out flyers and lanyards and offered trays of chicken wings. The food was stacked on tables featuring posters of a sweating robot, with the words: “We’re not machines, we’re human beings.”

In the aftermath of the JFK8 vote, every Amazon facility in the country contacted the Amazon Labor Union, according to Smalls. The LDJ5 vote will be the first test of whether the dam has broken. As a result, it has drawn significant political attention, with Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez visiting before the vote to stand in solidarity with the union.

If the organizers’ prospects are uncertain, one thing is clear: Smalls and the ALU are charting a new path forward for worker-led unionization outside of the established structures of organized labor.

“Many of the labor unions are very disconnected from the workers that they serve,” says Medina, adding that many of the officers in the big labor unions are “out of grad school.”

“They mean well,” she adds. “But there’s just a slightly different class composition.”

Experts say that the activism of the past few years—from #MeToo to Black Lives Matter to walkouts at major tech companies— has seeped into organized labor. The new model is “young people organizing young people, it’s non-white people organizing majority non-white workforces,” says Wilma Liebman, who served as chair of the National Labor Relations Board under President Obama. “Unions clearly have to adapt to the changing demographic of the workforces.”

The Amazon Labor Union is now inundated with support. Randi Weingarten of the American Federation of Teachers has promised a six-figure donation, according to an adviser, which could help the ALU get better office space. Sean O’Brien of the Teamsters Union told TIME that organized labor as a whole needs to “rally around this victory,” and that it creates an opening for a broader labor offensive against behemoths like Amazon.

“The Teamsters are gonna make a run at Amazon,” O’Brien says. “Our role in this whole thing is to provide them as much support and resources as needed, so that if they ever do get to the bargaining table, there are area standards that are met and kept.”

While Smalls is grateful for the help, he’s made sure that the other unions know who felled the giant. “They understand that this is our territory, and they’re giving us support with no strings attached,” he says. “They have to learn from us.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Charlotte Alter/New York City at charlotte.alter@time.com