One million people have died of COVID-19 in the U.S. Each death was more than a number: It was a lost parent, child, partner, or other loved one.

The pandemic has affected us all, but certain groups have suffered disproportionately throughout it. TIME spoke with three people who lost family members to the same devastating disease—COVID-19—but under very different circumstances.

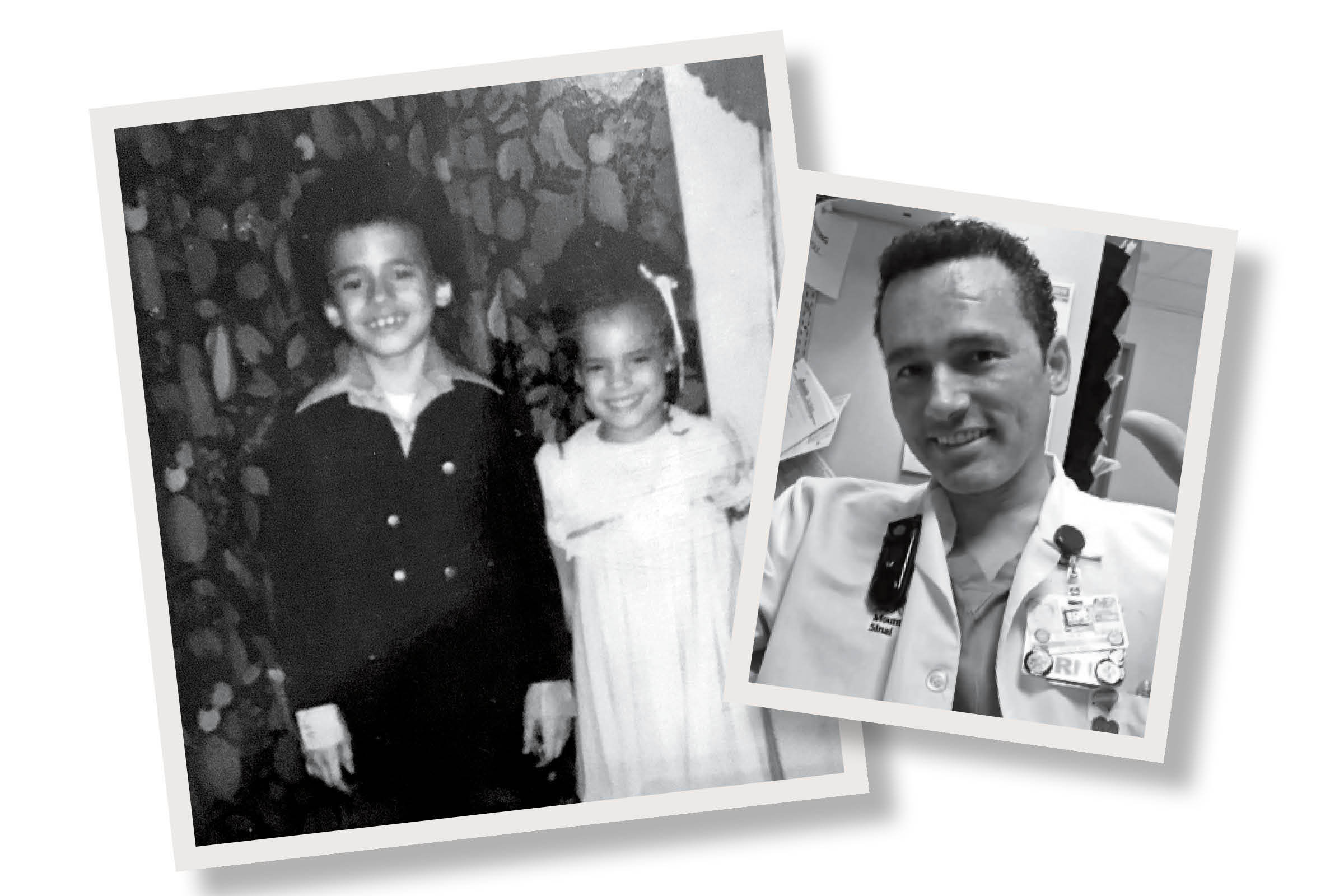

Kious ‘James’ Kelly

New York City, age 48

When COVID-19 began to ravage the U.S. in March 2020, health care workers were highly exposed to the virus. Many did not have access to adequate personal protective equipment—including Kious “James” Kelly, an assistant nurse manager at Mount Sinai West hospital in New York City. On March 24, Kelly died from COVID-19 after helping his team care for patients with the new disease.

His sister Marya Patrice Sherron, a 48-year-old writer and consultant who appeared on the most recent season of Survivor, remembers his life and impact.

My brother has always been my hero and my idol. I remember always running to him because he could literally fix anything. When I was a kid, the saying was “If you’re in trouble, go to James. James will fix it.” He was so logical and methodical, but also humorous, super smart, and talented artistically.

He was 2½ years older than me, but I acted 10 years older than him. He would dance in the grocery store, leaping and pirouetting. I hated it as a kid. I was so embarrassed. He did not care. The world was his stage. It didn’t matter where we were; if he was gonna dance, he was gonna dance. That is actually one of my fondest memories now.

He eventually moved to New York City and became a dancer, but it’s a short career. I remember him calling me and saying, “For my second act, I want to help people.” So that’s what he did, by becoming a nurse.

It was very hard, but he loved being a nurse. He had this special way with his patients. Every time he walked into a room, it got brighter and warmer. You couldn’t not notice he was there. He just had a powerful and peaceful yet exciting aura. Everybody responded.

When COVID-19 first started spreading in New York City in 2020, I didn’t know enough to be afraid for him. I was very stressed about our parents, because they’re older and had both been sick the year before. It didn’t occur to me to be worried about James, because there was so much we didn’t know at that point.

His sickness happened so fast. I found out he had COVID-19 on March 18, 2020. He was intubated and put on a ventilator the same day. When he texted me to tell me that he had COVID, I knew that my worry had been in the wrong place. I remember lying there in bed with this very heavy feeling. It was hard to even get someone on the phone with us at the hospital. He passed on March 24, 2020.

I blame the hospital for his death in the moments that I need someone to blame, but I don’t when I’m more logical. They had issues with getting people personal protective equipment, but I realize that they really didn’t know what to do either. It’s so tragic, but I don’t know that there really is someone at fault.

Hitting 1 million deaths in the U.S. is overwhelming to think about. I have screenshots from when the death toll was around 600. When my brother passed, it was still under 1,000 in the U.S. I hate saying this, but there’s part of me that has just had to shut down a little bit emotionally, after going through two years of people not wearing masks, not getting vaccinated, so much death. It’s all been so hurtful. It’s almost too much to digest. My brother didn’t even have an opportunity to get vaccinated.

I wish I could just scream on a mountain, “Love your neighbor.” It sounds so clichéd, but my mask isn’t for me; it is because I’m thinking about someone else and preventing them from going through what my family went through. If I can do something to keep others safe, then I’m going to. That’s all it comes down to. Every single one of those people who died has impacted the circle around them, whether it’s kids or mothers or siblings or people in the community. We can’t understand that when we just see the number. It’s very difficult, very sad, and to some degree, unnecessary.

I want to be more like James. Even in his absence, he left me with some very beautiful gifts. He lived fearlessly, and he pursued his dreams whatever they were. Dream big, live big, and don’t regret things. Those values are just ingrained in me now, partly to make him proud.

I’m finally going to be fearless. It’s so strange for something so hurtful to also produce fruit, to bloom and flower. He continues to give me gifts from the way that he lived his life. I’m grateful that I got to be his sister.

—As told to Jamie Ducharme

Brenda Perryman and Pearlie Louie

Detroit, ages 71 and 100

COVID-19 has killed people of color far beyond proportion. One reason is that these groups have higher rates of underlying conditions than white Americans. For example, up to 40% of Americans who died from COVID-19 had diabetes, a condition that hits Black Americans hard.

Brenda Perryman, 71, had Type 2 diabetes and died in April 2020. Her 100-year-old mother, Pearlie Louie, was on dialysis and died a week later. Both succumbed to COVID-19. Had a vaccine been available, they would have qualified for priority access to the shots. Heather Perryman-Tanks remembers her mother and grandmother and the mark they left on their city.

My mother was famous here. After she died, I woke up to her face on the news on three different stations saying that today we lost someone special. She was a drama teacher at a high school and an advocate for the arts with the city of Detroit. She taught students and years later taught their children. Everywhere we went, people stopped her and said, “Ms. Perryman, Ms. Perryman, we wanted to say hello.” She was always out doing public speaking for the arts and hugging people and all that, so I think that’s how she caught COVID.

She first got sick around March 20, 2020, and I could hear her coughing real bad. I was like, “Mom, you sound terrible,” and she said, “I’m fine.” But by the 26th, she had to go to the hospital—and that was the last time I laid eyes on her in person. Later, I saw her on FaceTime when she was in the hospital and had the breathing mask on.

She said, “Heather, I’m not doing well.”

I screamed, “Mom, you’ve got to fight for me—please fight, please fight!”

I called the doctor, and all he could say was “Well, she’s got diabetes, and if we can’t get her breathing again, I don’t know what to tell you.” They called us later and said they had to ventilate her. I questioned whether it was necessary, but my mother had already agreed to it, so there was nothing I could do.

They wouldn’t let me or my husband in to see her, so he drove me to the parking garage near the hospital, and I just cried and screamed for my mom from the outside. She died a week later.

My grandmother was in a nursing home at the time, and she knew my mother was sick. They tested everyone at the nursing home, and everybody who was sick, they sent to the hospital. My grandmother had COVID-19, so she went. I called her on the Tuesday before she died and asked her how she was doing. She was still in her right mind, and she said, “I’m just resting.” But I could hear that her breath was leaving her.

My mother passed on April 5. The doctors told us not to tell my grandmother that she had died, so we didn’t. My grandmother died on April 12. She was 100, and it took COVID-19 to kill her.

My mother and grandmother were best friends, and I always knew that when my grandmother died, I would have to comfort my mother. As it turned out, I didn’t have to comfort either one of them. But still, I lost half of my heart when they died. To lose them both within a week was like an out-of-body experience for me.

The African American community was really hit pretty hard by COVID. They always say that African Americans have more underlying conditions—more diabetes, more heart failure, more whatnot. I’m not going to say anybody did Black people wrong. But down here in our part of Detroit, you rarely saw anybody in the Caucasian community die. It was always in our community. Somebody’s uncle, somebody’s brother, somebody’s mother.

This was early in the pandemic, and the hospitals didn’t know what they were doing. They were sometimes just sending people home, and they died there. It was so overwhelming.

We’ve now reached 1 million people dying in the U.S. I see those numbers on TV and think, Oh my God, I can’t believe that. You never think that you will be part of that or anybody you know will be part of that. But my mother and my grandmother are two little people who are part of that statistic. Later on, my husband’s grandmother died of COVID-19 too, so it’s actually three people. The disease hit this family hard.

That’s why I feel like with the vaccines available now, I should do all I can—for my mother and my grandmother. I preach vaccines. My son is 16, and he’s had his booster. I don’t want him to have to go through what they went through.

—As told to Jeffrey Kluger

Clint and Carla Smith

Hogansville, Ga., ages 62 and 62

After vaccines became widely available in the U.S., the burden of COVID-19 deaths shifted onto unvaccinated adults—and onto heavily Republican parts of the country, where uptake of the shots was lowest (a trend that continues today).

In August 2021, during the Delta variant surge, husband and wife Brandon “Clint” Smith and Carla Smith of Hogansville, Ga., died from COVID-19, two days apart. Neither had been vaccinated. Elana Brown, 33, remembers her parents.

You hope that even if you have to lose one parent, at least you’ll have the other. But when you haven’t even had a chance to grieve the first one before the second one goes, there are no words for that. It’s a double punch straight to your heart.

They were good people. They were fun. Mom was super eccentric; she took her turtle, Houdini, in her purse everywhere she went. Dad was quiet, one of those listen-before-you-speak people. They got married when I was 13, but I was friends with him first; he was the guy next door, a motorcycle-riding long-haired bachelor. But he was just a soft, cuddly teddy bear. I called him Daddy from 4 years old on.

My parents were extremely religious. I feel like sometimes they took it too far. It reached conspiracy-theory level: they said Trump was great but Biden was the Antichrist. I begged them to get the vaccine. They felt like COVID was a hoax at first, and they thought the vaccines were filled with microchips. They felt like right now, we’re at the end times, and the vaccine had the “mark of the beast,” a sign of evil. They were so mad when I posted on Facebook that I’d gotten vaccinated. They were like, “You don’t know that they’re not tracking you, you don’t know that it doesn’t cause cancer. I really hope that you don’t die.”

In counseling, I’m still working through how they contracted COVID-19. My parents told me that when they brought a friend to a hospital emergency room, they had felt led to pray for a man sitting in the corner. Before they even touched him, he told them, “You may want to get away from me. I have COVID-19, and I’m really sick.” But they laid hands on him and prayed for him. Less than a week later, my mom had shortness of breath.

I had to make the call to take them off life support a couple weeks later. After we took my mom off, the nurse turned the iPad so I could see her. It was terrifying; she didn’t look alive. She always loved to hear me sing, so I sang one of her favorite songs.

The exact same day, my dad’s organs began to shut down. I know this sounds crazy, but I think he could feel that she was gone. He loved her with every fiber of his being. Before he went on the ventilator, he called me, and we said, “I love you.” With Mom, I didn’t get to say goodbye.

I’m angry because they didn’t have to die. They didn’t even have to contract COVID that day. It feels very selfish. I don’t want to speak ill of the dead—especially not my parents—but I feel like they should have thought about what it would do to the people around them. I’ve never seen so much pain in my grandmother’s eyes. All she could say was, “You are not supposed to outlive your children.” Oh, it made my heart just crack into a million pieces.

I tell other unvaccinated people about the suffering my parents went through: how in the end, I wasn’t allowed to go into their room and hold their hand and tell them that I love them as they died. Everybody’s like, “I know that God is going to save me.” And they’re right, except he already did. He had these brilliant people come up with a vaccine that can save you. And you refuse to accept his help.

—As told to Tara Law

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jamie Ducharme at jamie.ducharme@time.com and Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com