As we watch the murderous carnage that Putin has unleashed against innocent Ukrainians, we are all trying to understand Putin’s motivations. Some say he’s reacting to NATO expansion, others contend that Putin can’t abide a Western-leaning Ukraine. Still others offer that Putin so laments the break-up of the Soviet Union that he wants to reassemble it.

From my perspective, it’s not due to any of these reasons. It’s simply about money. Unlike most other governments, Russia’s is not there to serve the people, but to enrich senior officials through endemic corruption. The more senior you are, the richer you get. And the most senior person, Vladimir Putin, has become the richest. I estimate his wealth to be well north of $200 billion.

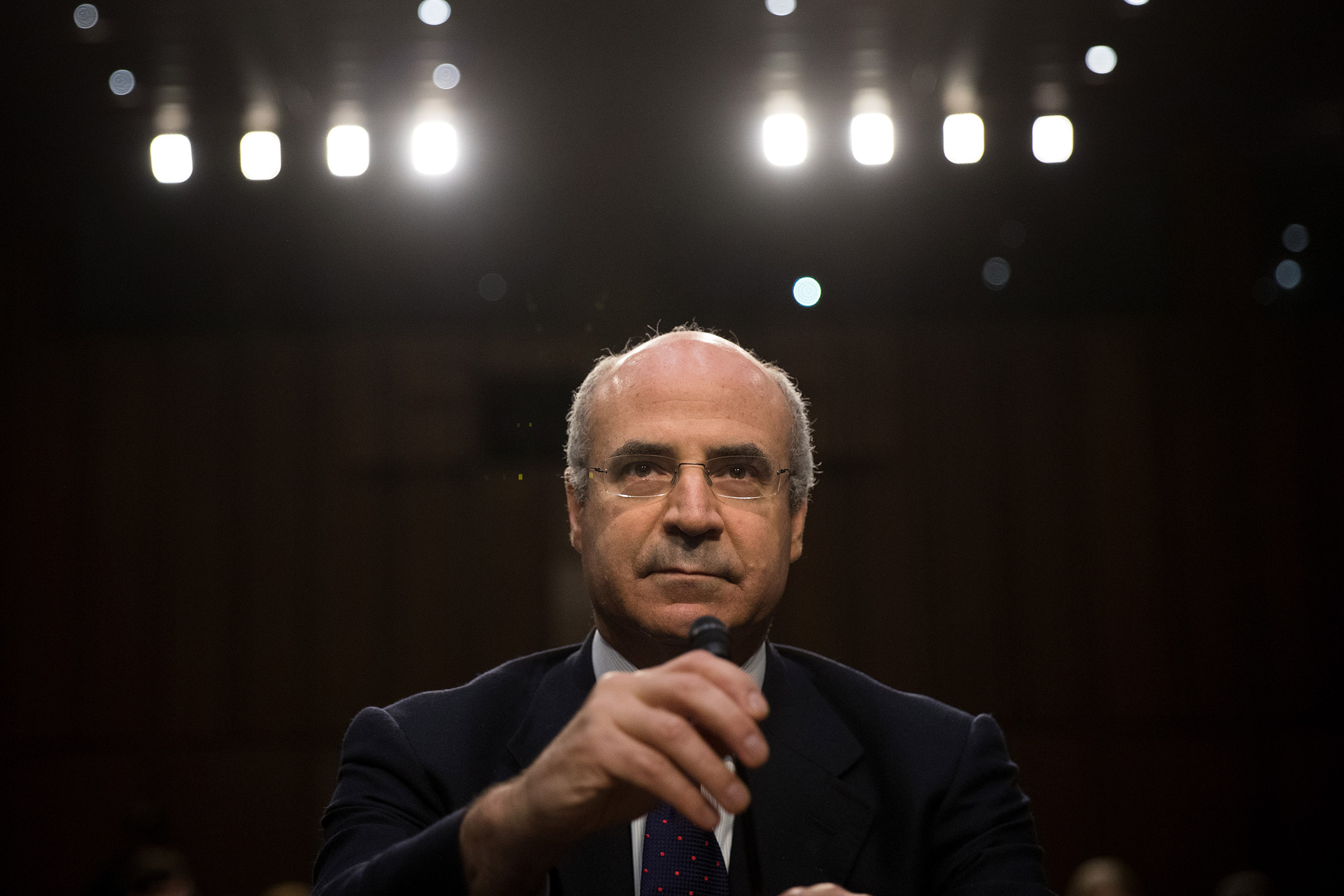

I’ve seen how Russian corruption works with my own eyes. For a decade, between 1996 and 2005, I ran the largest foreign investment firm in Russia. My business model was simple: buy deeply undervalued shares in Russian companies, expose these companies’ corruption, and then watch their share prices rise as the companies were forced to clean up. It worked like a charm. However, as you can imagine, the oligarchs and corrupt officials who were doing the stealing weren’t too happy with me. In November 2005, I was kicked out of the country and declared a threat to Russian national security.

I moved to London and regrouped with my small team. We also went about liquidating the fund’s Russian assets. In 2006, our holding companies reported a profit of $1 billion, paying $230 million in taxes to the Russian Treasury. I was done with Russia.

But Russia was not done with me.

In 2007, my office in Moscow was raided by the Russian Interior Ministry. All of our documents were seized, and these were used to perpetrate a highly complex tax rebate fraud scheme to steal $230 million from the Russian Treasury that our investment holding companies had previously paid.

My lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, discovered the crime, testified against the officials involved, and in retaliation was arrested. He was held for 358 days, tortured, and killed on November 16, 2009 in Russian police custody. He was only 37 years old. He left behind a wife, a seven-year-old son, and a loving mother.

Since then, it has been my life’s mission to get justice for Sergei. Unfortunately, it was impossible to get justice in Russia. The Russian government promoted the people who had killed Sergei, giving them state honors. Three years after Sergei’s murder, the Russian government put him on trial in the first-ever case against a dead man in Russian history.

This story is a microcosm of what happens every day in Russia. You need to multiply the crime that Sergei discovered by 1,000 to begin to appreciate how much has been stolen by Putin and his cronies.

The problem for Putin is that this level of corruption is unsustainable. Russia presents itself as a democracy to its people. And those people are the ones deprived of health care, education, paved roads, and a decent standard of living so that senior officials in the Putin regime can enjoy yachts, private jets, and villas in the South of France. No matter what Russian propagandists peddle, eventually people will get angry. Putin looked around and what he saw frightened him. In Kazakhstan, another corrupt dictator, Nursultan Nazarbayev, was ousted earlier this year in January. In Belarus, President Alexander Lukashenko was almost ousted following the fraudulent 2019 election. It was only because of Putin’s intervention that Lukashenko is still in power.

So Putin dug into the dictator’s playbook and started a war. Now, instead of the Russian people being mad at him, they can be mad at “Nazified” Ukrainians, or the U.S., or NATO.

So far, he seems to be succeeding with his approval ratings in Russia around 83 percent.

It is now plain that Putin is evil. This is not breathless hyperbole. It is fact. He has no regard for human life, and only lusts over power and money. In his calculus, money is power, and vice versa.

Amazingly, Putin himself has now been sanctioned by the West. But finding the whereabouts of his money is no easy task. I’ve spent the last 14 years trying to understand the dark money flowing out of Russia. Once we found it, there was a huge price to pay.

On April 3, 2016, the British newspaper the Guardian, published an article titled, Revealed: the $2bn offshore trail that leads to Vladimir Putin. The author was part of a consortium of 370 journalists from 80 countries reporting on a data leak known as The Panama Papers.

Central to the leak were over 11 million documents held by the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca. The files revealed financial details of hundreds of thousands of offshore companies and accounts belonging to wealthy people from around the world.

The articles were divided by country, and each country had a star. In Russia, that star was classical cellist named Sergei Roldugin.

Roldugin wasn’t just a cellist, but also Putin’s best friend going back to the 1970s. Even though Roldugin professed to drive a used car and play a secondhand cello, he controlled companies that had accumulated billions of dollars of assets since Putin took power, effectively making him the richest musician in the world.

A quick Google search reveals that the richest musicians are Jay-Z, Sir Paul McCartney, and Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber, who are each worth around $1.25 billion. Yo-Yo Ma is probably the world’s wealthiest cellist, and he’s worth “only” about $25 million.

How had Roldugin become so wealthy? The answer, in my opinion, is that this cellist was serving as a nominee for his longtime friend, Vladimir Putin.

Read More: Ukraine Is Our Past and Our Future

As anyone who follows Russia knows, Putin loves money. But because he’s president, he can only earn his official salary (which is around $300,000 a year), and he can’t hold any assets beyond those he accumulated before he was in government. If he did, anyone who got hold of a copy of a bank statement or a property registry with his name on it could use it as leverage to blackmail him. Putin is well aware of this, because he’s used this tactic on many occasions against his own enemies.

Therefore, Putin needed others to hold his money so that no paper trail led back to him. For this, he needed people he could trust. In any mafia-like organization, these people are rare birds. There is no commodity more valuable than trust.

Roldugin was one such person for Putin. From the moment the two had met on the streets of Leningrad in their 20s, they were like brothers. Roldugin introduced Putin to his wife; he was the godfather to Putin’s firstborn daughter; and through the decades they had remained the closest of friends.

For us, this news was potentially even more dramatic. If we could somehow link any of the $230 million tax refund that Sergei Magnitsky had been killed over to Putin through Roldugin, it would be a game-changer.

Two days later, an obscure Lithuanian website reported that one of the companies linked to Roldugin had received $800,000 from an account at a Lithuanian bank. This account belonged to a shell company called Delco Networks.

We searched our money laundering database and found that this $800,000 was connected to the $230 million tax refund. After leaving Russia, the money had passed through a series of banks in Moldova, Estonia, and, ultimately, Lithuania.

We could now link the crime that Sergei Magnitsky had exposed and been killed over to Roldugin. And from Roldugin, we could link it to Russian president Vladimir Putin.

This explained everything.

When Sergei was killed, Putin could have had the perpetrators of the tax rebate fraud prosecuted, but he didn’t. When the international community demanded justice for Sergei, Putin exonerated everyone involved. When the Magnitsky Act passed in in the United States, freezing all assets of those implicated in Sergei’s murder, Putin retaliated by banning the adoption of Russian orphans by American families. Before the law passed, Putin’s government had even arranged for Dmitry Klyuev, a convicted mobster, along with his consigliere, Andrei Pavlov, both private citizens, to attend the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly in Monaco to lobby against the Magnitsky Act, as if they were some sort of special government envoys.

Why had Putin gone to such lengths to protect a group of crooked officials and organized criminals?

Because, quite simply, he was protecting himself.

Out of $230 million, $800,000 is a pittance. But sums like these add up. It’s like charging $5 for a toll. For one car, it’s nothing, but after a million cars, you’ve collected a fortune.

Mossack Fonseca was merely one of hundreds of offshore trust companies. If these other companies’ books were similarly exposed, I was sure we would find other trustees of Vladimir Putin who had received other tranches of the $230 million. And this was just one crime among thousands and thousands of crimes that had taken place in Russia since Putin took power.

We were looking at the tip of an enormous iceberg.

The Magnitsky Act says that Russian human rights violators will have their assets frozen in the West. It also says that beneficiaries of the $230 million crime will be sanctioned. That Putin was a human rights violator was not in dispute, but now he ticked both boxes.

The Magnitsky Act put all of his wealth and power at risk. That made him a very angry man. His crusade against the Magnitsky Act wasn’t just philosophical, it was personal.

We had genuinely hit Vladimir Putin’s Achilles’ heel.

At 8:00 a.m. on Monday, July 16, 2018, Trump and Putin were in the midst of their summit in Helsinki, Finland. I was in Aspen with my family. I set up my laptop at the end of the dining room table, a view of the mountains to the west over my shoulder.

I needed to get some work done, and I didn’t want any distractions. My kids usually run riot all over the house, but that day I put the dining room off-limits. I also put restraints on myself, laying down my phone. After two hours of work, I turned over my phone. The screen was flush with notifications. I had dozens of messages—texts, emails, DMs, voicemails, everything.

I opened the first email. “Bill, are you watching Helsinki??”

I scrolled through my inbox. “That was the scariest, most fucked-up thing I have ever seen,” one friend said. Another wrote, “If you need a place to hide, we will put you in our mountain house!”

What the hell was going on? I found the earliest email about Helsinki, from the correspondent Ali Velshi at MSNBC. The subject was to the point: “Putin talking about you now.”

Fuck.

I put down my phone and went online. It didn’t take long to find the post-summit press conference. The two leaders were onstage at twin lecterns, and their body language couldn’t have been more different. Putin looked like he owned the place, while Trump glowered and slumped his shoulders, looking anything but presidential.

The shocking moment came when a Reuters reporter asked: President Putin, “will you consider extraditing the twelve Russian officials that were indicted last week by a U.S. grand jury?” Robert Mueller, the special counsel who had been in charge of investigating Russian involvement in the 2016 presidential election, as well as possible Russian links to the Trump campaign, had made an unexpected announcement the week before. His office was indicting 12 Russian GRU officers (the GRU is Russia’s military intelligence wing), accusing them of hacking the Democratic National Committee and interfering in the election to help Trump win.

Putin smiled and nodded confidently, looking like he’d spent the whole weekend preparing for this moment. “We can meet you halfway … We can actually permit representatives of the United States, including this very commission headed by Mr. Mueller. We can let them into the country. They can be present at questioning. In this case there’s another condition. This kind of effort should be a mutual one. We would expect that the Americans would reciprocate… For instance, we can bring up Mr. Browder in this particular case.”

Read More: The Man Putin Fears

I had to watch it several times to make sure that I’d heard it correctly. Somehow, Putin, standing next to the President of the United States, was suggesting swapping 12 Russian GRU officers—for me!

I waited for Trump’s reaction. Surely, he would reject this out of hand.

But he didn’t. “I think that’s an incredible offer,” he said, suggesting he was ready to trade me.

Rationally, I understood the gravity of the situation, but emotionally I was too shaken to take it in. It was like being in a serious car accident. I knew I’d just been injured, but I had no idea how badly.

As I tried to assess the damage, the main thing I kept coming back to was whether it was safe for me to stay in America. My original, nebulous concern that some Russian assassin might try to kill me had now been overtaken by the very real fear that the President of the United States would hand me over to the Russians.

My first inclination was to get the hell out of America. But my wife, Elena, calmed me down and convinced me to stay. “Right now,” she said, “the world wants to know: who is Bill Browder?”

She was right. I spent the rest of that day on TV, explaining the Magnitsky Act to anyone who’d listen. My main message? Putin is evil, and this idea of his was nothing more than a test for the West. Would the West pass? Only time would tell.

The next morning, at 6:30 a.m., my wife Elena jolted me awake, waving a piece of paper in my face. “You’ve got to see this, honey!”

Elena is originally from Russia, and she’d gotten up before sunrise to read the Russian news. That morning, the Russian General Prosecutor’s Office had issued a list of 11 additional people the Russians wanted the United States to hand over in exchange for the 12 GRU officers. Russians love symmetry in these matters. The United States wanted 12, which meant Russia wanted 12.

I propped myself up and took the paper. The Russians wanted Mike McFaul, the former US ambassador to Russia; my friend Kyle Parker, the Congressional staffer who originally drafted the Magnitsky Act; three Special Agents from the Department of Homeland Security who had been involved in investigating a Russian money laundering scheme involving a Cyprus-registered company named Prevezon that had received some of the $230 million; Jonathan Winer, the Washington lawyer and former State Department official who had come up with the original idea for the Magnitsky Act; and David Kramer, another ex–State Department official and the former head of the human rights NGO Freedom House, who’d advocated for the Magnitsky Act alongside Boris Nemtsov and me. There were four additional names on the list, but the main common denominators were either involvement in the Magnitsky Act or participation in the Prevezon case.

What were the Russians accusing us of? The day before, Putin alleged that my “business associates” and I had “earned over $1.5 billion in Russia,” “never paid any taxes,” and then, to get Trump’s attention, gave “$400 million as a contribution to the campaign of Hillary Clinton.” (The actual amount was zero.) Putin went on to say, “We have solid reason to believe that some intelligence officers guided these transactions.” Putin was accusing Ambassador McFaul, Kyle Parker, the three DHS agents, and everyone else on the list of being part of my “criminal enterprise.”

This was classic Russian projection. We weren’t the victims, they were. They weren’t the criminals, we were. Instead of the Dmitri Klyuev Organized Crime Group working with corrupt Russian officials to launder vast sums of money, it was the Bill Browder Organized Crime Group working with corrupt American officials to launder vast sums of money.

Elena and I looked at each other and smiled. Once again, Putin had way overplayed his hand.

It was one thing to go after a private person like me, who wasn’t even an American citizen. That might have been distasteful, but in the final analysis how many people cared about me? It was entirely different to ask for a former U.S. ambassador, a congressional staffer, and rank-and-file DHS agents. If Trump obliged Putin, it would set a disastrous precedent.

The day after that, at a White House press conference, Maggie Haberman from the New York Times asked Trump’s press secretary, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, “Russian authorities yesterday named several Americans they want to question that they claim are involved in Bill Browder’s quote-unquote ‘crimes,’ in their terms, including the former ambassador to Russia, Mike McFaul. Does President Trump support that idea? Is he open to having US officials questioned by Russia?”

This was the moment all of Washington had been waiting for.

Huckabee Sanders didn’t waver. “The president is going to meet with his team and we’ll let you know when we have an announcement on that.” She added that Trump “said it was an interesting idea. He wants to work with his team and determine if there is any validity that would be helpful to the process.”

What the fuck? They were still thinking about this?!

I felt like the floor had fallen out from under me—again. Every reasonable person in Trump’s orbit must have been telling him this was insanity, yet he was still mulling it over.

Luckily, everyone else in Washington seemed to agree with me.

The tidal wave of indignation was towering, and the Senate quickly organized a vote on a resolution calling on Trump never to follow through on Putin’s “incredible offer.”

The administration could sense this wave was about to come crashing down on them. An hour before the vote, the White House finally backtracked. Huckabee Sanders announced, “It is a proposal that was made in sincerity by President Putin, but President Trump disagrees with it.”

This was hardly the robust rejection Washington expected. It seemed like Trump was apologizing to Putin, shrugging his shoulders and saying, “Hey, buddy, I tried, but they won’t let me.”

That afternoon, the Senate voted on the resolution. It passed 98–0.

No one would be handed over to the Russians.

Adapted from Browder’s new book, Freezing Order: A True Story of Money Laundering, Murder, and Surviving Vladimir Putin’s Wrath, published by Simon & Schuster.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com