The wine was too warm for Kristina Kvien, the top U.S. envoy to Ukraine, so she stood up to get some ice cubes from a waiter at the bar. It was close to midnight in eastern Poland, the 11th night of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and for Kvien it was the end of a long day of meetings with U.S. military brass, members of Congress, and senior Biden Administration officials. Her boss, Secretary of State Antony Blinken, had left the city of Rzeszow a few hours earlier after visiting the U.S. supply lines to Ukraine. Kvien had gone to see him off.

“It’s been crazy here,” she told me that night in the restaurant of a hotel in the city center, which has served as her team’s headquarters since U.S. diplomats evacuated Ukraine. “A couple of days ago, I was sitting at this table with Sean Penn.” The American actor, who was working on a film in Ukraine when the invasion started, had been forced to flee over the border, abandoning his car at the side of the road and walking into Poland with a flood of refugees. Kvien ran into him when he finally made it to the hotel. “It feels a bit like Casablanca,” she says.

Spend a few days driving back and forth across this border, and the plot of that wartime classic comes readily to mind. The film premiered in 1942, less than a year after the attack on Pearl Harbor forced the U.S. to join World War II. Eighty years later, the U.S. again finds itself drawn into a major European war, and there is no better place to witness its involvement than on the plains of eastern Poland, where a flood of assistance from the U.S. and its allies has given Ukraine its best chance of surviving this war, and maybe even winning it. “All of us are deeply, deeply committed to this cause,” says Kvien, who has been the top U.S. diplomat in Ukraine since the start of 2020. “We’re here to help. We’re part of it.”

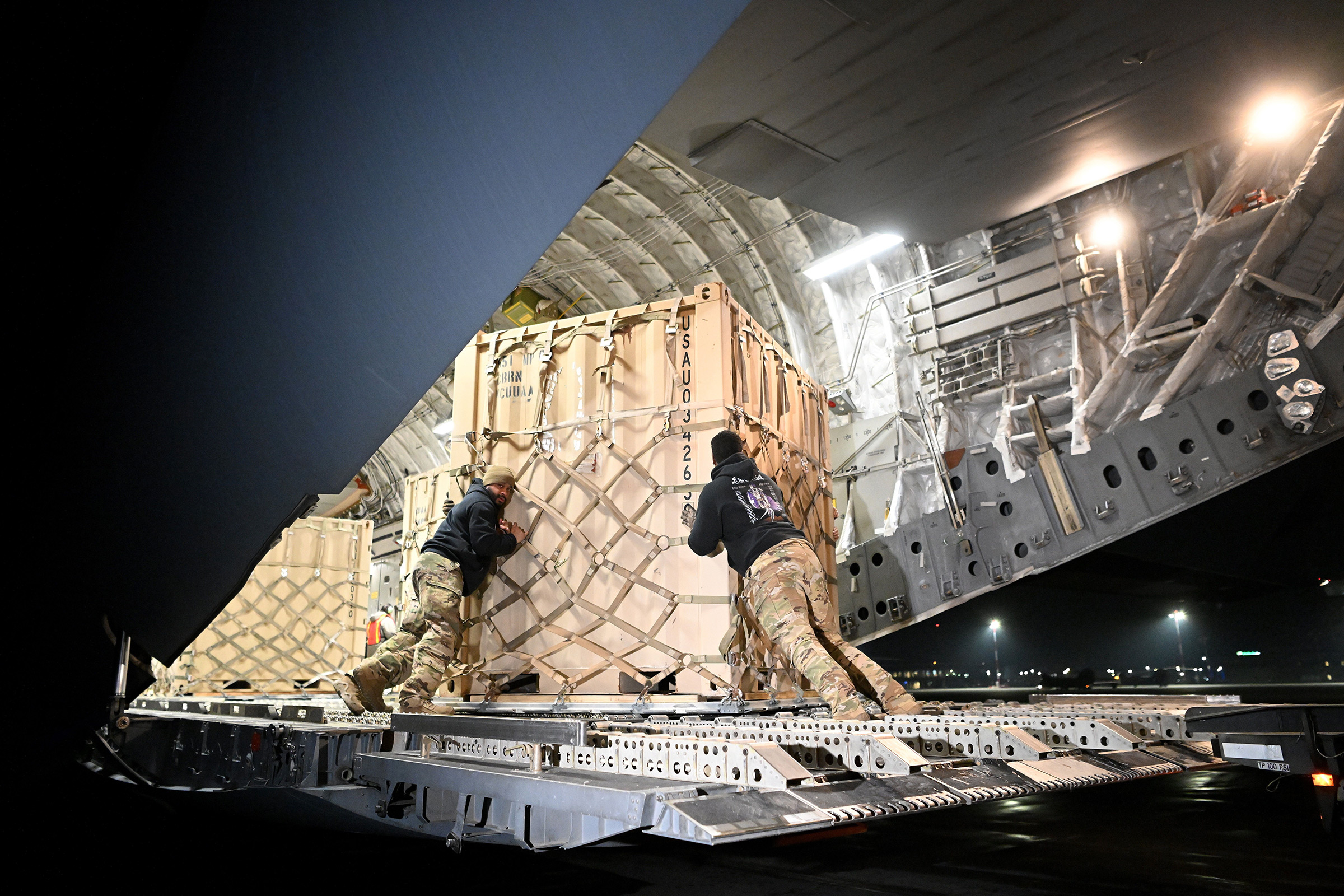

Since the end of February, dozens of U.S. military cargo planes have landed on airfields near the border, packed to the brim with weapons. According to the Pentagon, it’s the largest authorized transfer of arms in history from the U.S. military to any foreign country. Huge convoys of humanitarian aid have also poured across the border, ferrying everything from diapers to bulletproof vests in eclectic modes of transport: a Belgian ambulance on loan to a playwright from Berlin; a minivan helmed by a Ukrainian commando; the jeep of a British car salesman, who had driven for days to join the fight as a volunteer, one of thousands coming on their own accord from the U.S. and Europe to help Ukraine defend itself.

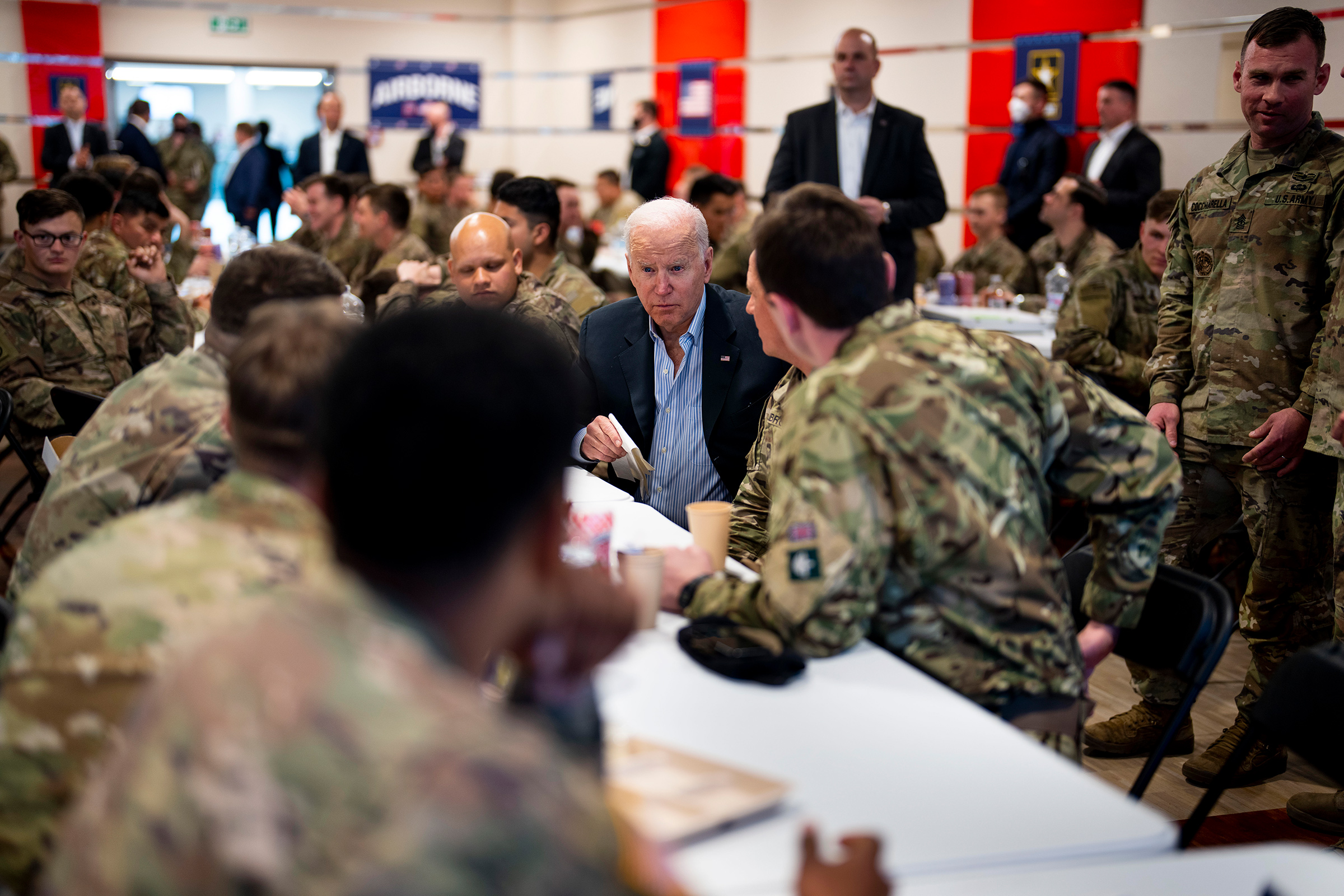

My travels through this corridor made one thing clear: the U.S. is a part of this war, even if its troops are not pulling the triggers. There are no plans to send any American forces for combat operations in Ukraine, a red line that President Joe Biden drew again during his trip to Poland on March 25. But just about anything short of that line seems to be fair game for Biden, and that leaves the U.S. with plenty of options for making sure the costs of this war in blood and money become unbearable for Russia, its military, and its President.

As the humanitarian toll of the Russian onslaught intensifies, Biden has ratcheted up his rhetoric in ways that risk drawing the U.S. even deeper into a conflict with a nuclear power. After meeting with U.S. troops in eastern Poland on March 25, Biden called Vladimir Putin a “war criminal.” In a speech the next day, he questioned whether the Russian leader can remain in power after all the suffering he has caused in Ukraine. Biden’s primary focus throughout the trip, however, was on the aid the U.S. is providing to Ukraine to alleviate that suffering. “They need it now,” he told officials coordinating that aid at the airport in Rzeszow. “They need it as rapidly as we can get it there.”

That airport, about an hour’s drive from the border with Ukraine, was also the spot where my journey began a few weeks earlier, following the river of aid toward supply hubs in western Ukraine for distribution to the war zone farther east.

The first stop along the way was the hotel in Rzeszow, an unlikely nerve center for the U.S. mission. Kvien, an alumnus of the U.S. Army War College, ended up here in early February, soon after U.S. intelligence concluded that a Russian invasion was imminent. Her priority at the time was to convince the Ukrainian government that the invasion was coming, and to help them get ready. That mission ran into a wall of denial from President Volodymyr Zelensky and virtually all his aides. Their government did little to prepare. Ukraine did not call up reservists, warn civilians, stockpile food, or move weapons into position. That made the supply lines from Poland even more critical once the invasion began on Feb. 24.

In his declaration of war early that morning, Putin warned that any country interfering in the invasion would face a Russian response “unlike any you have seen in your history.” Many analysts took this as a threat of nuclear escalation. A senior Russian diplomat later made the warning more explicit. “By pumping Ukraine with weapons,” said the diplomat, Sergei Ryabkov, the U.S. is making “not just a dangerous move, but an action that turns the corresponding convoys into legitimate targets.” Such threats did not stop the U.S. from rushing aid across the border. In the first three weeks of the invasion, President Biden approved $1 billion worth of military hardware for Ukraine, including five attack helicopters, 100 combat drones, thousands of anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles, and around 60 million rounds of ammunition.

U.S. troops from the 82nd Airborne have been deployed to eastern Poland, in part to ensure that Russia thinks twice about threatening these supply lines. “You are sitting at the forward edge of freedom,” General Mark Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told the troops during a stop in eastern Poland in early March.

It was one of many visits that Kvien and her team have helped to manage from their new base in Rzeszow. Congressional delegations have cycled through town. Republican Mike Pence, the former Vice President, paid a visit to see the U.S. support for Ukraine in action. “We haven’t taken a day off in about a month,” Kvien told me at the hotel restaurant. “The days have started to run together.”

The humanitarian aid convoy began to gather the next morning in a small Polish town near the border with Ukraine. Its organizer was Yuri Tyra, a longtime adviser to President Zelensky. The two have been friends since Zelensky’s early days as a comedian and actor. Beginning in 2014, when Russia launched its annexation of the Crimean peninsula, they have made a tradition of visiting soldiers on New Year’s Eve, delivering treats and gear to raise morale.

The start of the broader war in late February caught Tyra in his bathing suit, relaxing with his family in Brazil. He had been so sure that the buildup of Russian troops at the border was a bluff that he had decided to go on vacation. When Tyra heard the news, he sent a text message to Zelensky: “Coming to help.”

With that began a mad dash to gather supplies from all over Europe. A network of friends helped Tyra drum up support from community groups, churches, schools, and charity organizations. Truckloads of supplies soon began arriving at another friend’s mechanic shop in a Polish village near the border. By the time Tyra got there on March 6—his wife, their daughter, and a suitcase full of their holiday clothes in tow—the shop was piled high with boxes. From Finland, for Ukraine, read one of them. Another label, written in German, offered a meticulous list of the contents: 48 juice boxes, 10 bags of muesli, 40 pairs of socks.

More than a dozen volunteers had driven for days to bring it all to the border. One of them, Gennady Kurkin, was about to begin producing his play at a theater in New York City when the invasion started. When I asked about his motives for coming all the way from his home in Berlin, he countered with a question of his own: “How can anyone just carry on as normal when this is happening?” A few of the convoy runners had laid out a lunch of pickles, bread, cookies, and coffee in the back of the shop. Kurkin scarfed down cold meatballs from a can.

Before long the trucks were fully loaded, about a dozen in all, and we set off in a line behind Tyra’s car. He had given Kurkin and me an ambulance to drive, an old Belgian model that had been purchased and donated by volunteers in the Netherlands. They had stuffed the vehicle so full of medical supplies that we had trouble squeezing our backpacks inside.

The border with Ukraine was less than 15 miles away, but it took us seven hours to reach it. Coming out of Ukraine into Poland, the crossing was backed up with refugees, a vast column of women and children pulling roller suitcases and carrying pets under their arms. That was expected: more than a million of them had already fled the fighting. What surprised me was the traffic going in, a fleet of cars pushing into a war zone.

Many of them were aid convoys. Others carried Ukrainians who had been abroad when the invasion started and were rushing to find their families. At one point, a line of more than a dozen identical green trucks eased around the traffic on their way into Ukraine. One of Tyra’s convoy runners saw me staring at the vehicles, which had no identifying markers. “Zbroi,” he said in Ukrainian. Weapons.

It was well past midnight when we reached the border crossing, a system of tents and cordons where refugees were waiting in the cold to get inside. At the customs booth, a Ukrainian official looked at my U.S. passport and asked in a tired voice, “Foreign fighter?”

By the time we got across, the nightly curfew was in effect, prohibiting the convoy from carrying on until morning. But a group of Ukrainian special forces troops had come to the border to receive the aid, and they offered to drive me the rest of the way to Lviv that night. They were all in their 20s, dressed in camouflage, and had been making runs back and forth to the border since the invasion started. “It’s keeping us alive,” said a 27-year-old named Viktor as we cruised through the first Ukrainian checkpoint.

Since 2014, Viktor’s unit has taken part in joint military exercises with NATO troops. The training has come in handy, he says, as have the weapons shipments from the U.S., especially the shoulder–mounted rockets capable of downing a plane or piercing the armor of a tank.

But their own vehicles, Viktor noted, had no armor. We were driving in a dented minivan, its back seat loaded with boxes of aid: a power generator, some clothes, and food. “We’ve lost a lot of our men already,” he told me. “We’re fighting well. But we’re under-supplied. If you could get a message out there to the world, tell them we need a lot more armor.”

For about eight years, David Plaster, a former medic in the U.S. Army, has worked as a coordinator for foreign fighters in Ukraine. Local veterans’ groups took a liking to his first-aid seminars, usually delivered with a stream of off-color jokes. He made friends in Kyiv, learned the language, and started helping foreigners find suitable units to join. Those without combat training, he says, are better off heading home. “Nobody needs Americans roaming around in the war zone unsupervised,” he told me. “But if they’re capable, if they have the skills, they’re welcome to help.”

The tide of fighters from abroad has swelled considerably in the weeks since the Russian onslaught began. Within a week of the invasion, President Zelensky announced that 16,000 foreigners had volunteered to join what he called the new International Legion. Zelensky’s office launched a website with step-by-step instructions for enlistment, starting with an interview at a local Ukrainian embassy or consulate anywhere in the world.

Working in coordination with Ukraine’s armed forces, Plaster arranges for some of these foreign volunteers to teach locals the basic skills they need to defend themselves and stay alive, whether it’s applying a tourniquet or handling a weapon. One afternoon in early March, he was at a giant wholesale market in Lviv, loading up a basket with bottles of shampoo, deodorant, and hygiene wipes to distribute among the new arrivals from abroad. With him were a group of the foreign fighters. Three of them had just arrived, and in their rush to join the war they had neglected to bring some basics. An Australian sniper searched the aisles for nail clippers; they were sold out. On his way to the register, Plaster overheard two strangers with American accents and a shopping cart. “You here to join up?” he asked them. They looked us over, smiled, and confirmed that they had just arrived in Ukraine with plans to fight the Russians. Plaster gave them his number.

Some European leaders have tried to stop their citizens from going to the war zone to fight, especially if they are already actively serving in the military at home. “You should not go to Ukraine,” U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson said in response to reports that dozens of elite British troops and veterans, including the son of a British parliamentarian, were taking up Zelensky’s call to arms.

But most of the volunteers are ordinary civilians moved to help. Igor Gavrylko, who was working at a car dealership in western London when the invasion started, drove his Mitsubishi from there to Ukraine, linking up with Plaster on arrival. “I’ll go wherever I’m needed here,” Gavrylko told me.

We were at a well-appointed dormitory of a university near the city center. Plaster had arranged for a few dozen beds to be made available to new arrivals. His own room was already littered with pizza boxes, the mini-fridge stocked with beer. Many of the foreign fighters, he said, were being sent to a base in western Ukraine, about 10 miles from the border with Poland, for orientation. From there they would be deployed to the front. “You should go check it out,” Plaster told me.

I never got the chance. A few days later, a barrage of Russian cruise missiles struck that base, killing dozens. A Ukrainian soldier I had met sent me photos from the scene, showing a collapsed building and massive craters in the ground. One foreign fighter who survived, a British citizen named Jeremy, told me that he had helped pull the bodies of his dead and wounded comrades from the rubble. The clear message was that no one was off-limits.

The town closest to the base was full of checkpoints when I passed through on the way back to Poland. They were manned by local volunteers, young men in civilian clothes standing among piles of sandbags, flying Ukrainian flags. One of them stepped forward with a red and white baton and signaled for me to stop. A few of his friends, unarmed, stood behind him with nervous smiles. He asked where I was from and where I was headed. The U.S., I said, going to Poland. The young man pondered this for a long moment. “Carry on,” he said in Ukrainian. “And send them our thanks.”

Two days later my flight out of Poland departed from the airport in Rzeszow, taxiing near the U.S. military planes that had come to deliver weapons for Ukraine. Even from the highway, the planes were visible through a barbed-wire fence, maneuvering around the tarmac like big green whales. On a field nearby stood a few surface-to-air missile batteries, pointing toward the sky to defend against a Russian attack.

The morning of my flight, several friends and strangers had written to me, asking whether we were on the brink of war between the U.S. and Russia. One asked via email for the probability of World War III breaking out within a month. I didn’t know how to answer. If the U.S. is standing on such a precipice, it would look a lot like this airfield and the nearby border. No one can predict how Russia will respond to the lifeline the U.S. and its allies have created for Ukraine. But for the diplomats and convoy runners, the soldiers and volunteers who have kept the supplies flowing, the mission appears to be worth the risk. —With reporting by Simmone Shah and Julia Zorthian/New York

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com