This spring was supposed to be my nephew’s last semester of high school in Kyiv. He was studying for college entrance exams with a plan to major in computer science. Instead, he is figuring out schools that he can attend near Amsterdam where he is staying with a kind stranger who took him in as my nephew fled his home for the second time in his life. The first time was when he was 9 and he was forced to leave his birth city of Donetsk after Russian-backed separatists started a war for the Donbas region in 2014.

My nephew was one of 1.7 million pereselentsy, or internally displaced persons, who fled Crimea and Donbas for other parts of Ukraine. Now, war has come to them for the second time in their lives and they face the unknown once again.

As a Russian-American immigrant, I know what it’s like to leave everything and start from nothing. For my family back in the 1990s, coming to the U.S. was a choice. I wasn’t a refugee. I didn’t have to tape my windows in case of a blast or hide in a bomb shelter before finding a way to escape. And I certainly didn’t have to do that twice by the time I was 17.

For many pereselentsy, restarting their life within their own country hadn’t been easy. People in Ukraine, and in Russia for that matter, aren’t as mobile as Americans. They don’t typically go to college across the country or get jobs in another city far from where they grew up. In Donetsk, four generations of my family used to live within walking distance of each other. But that way of life is over now.

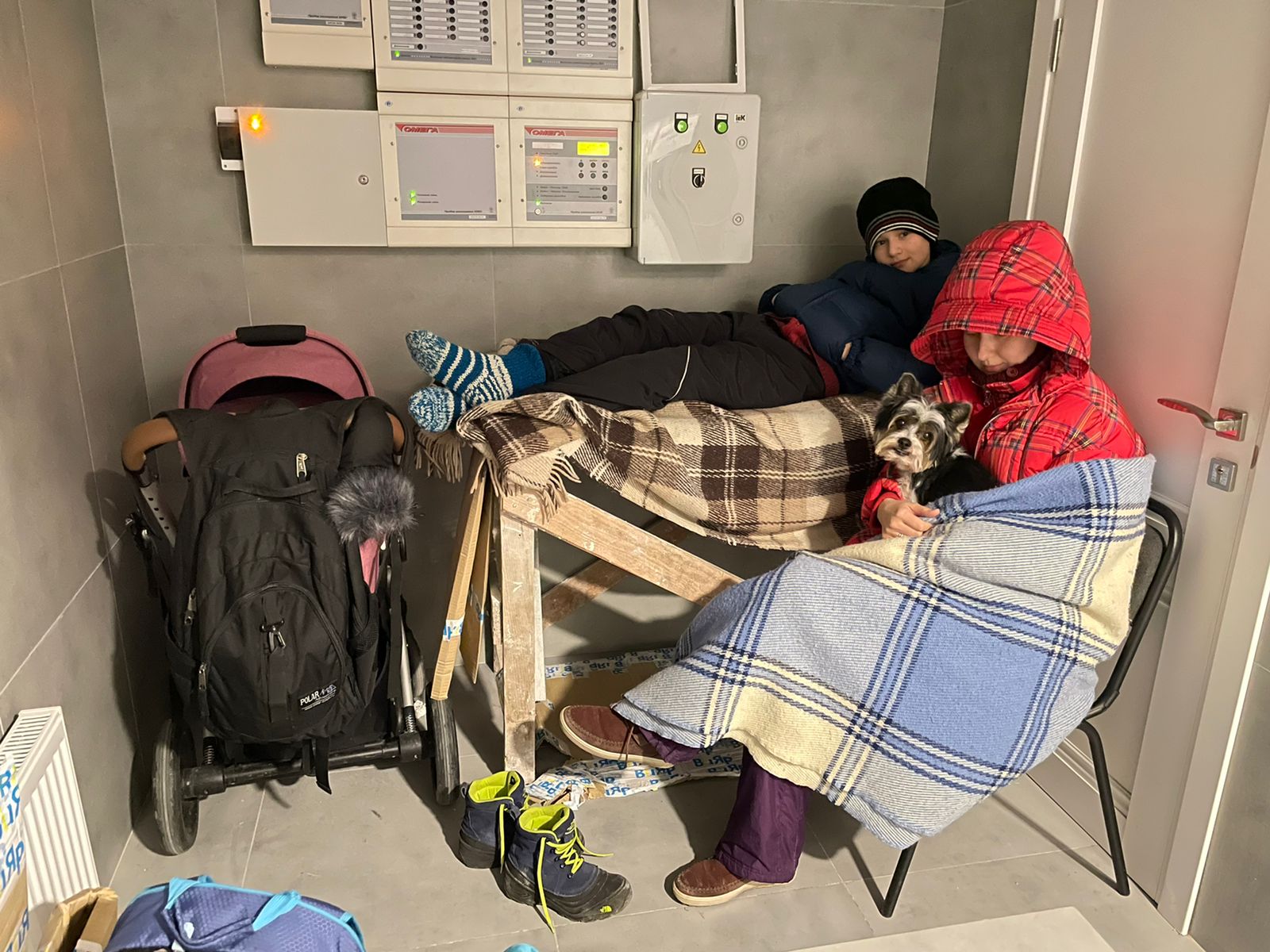

When the separatist war began eight years ago, the younger generation largely left the region. My cousins Anna and Mikhail were in their late 30s and it took them several years to scramble together a decent new life in Kyiv. Anna had to switch jobs, apartments, schools, and even cities before gaining some stability. Meanwhile, Mikhail had had several fitful starts before he finally rebuilt his career as an entrepreneur. Then, last year he told us he was getting married and they were having a baby. He bought a condo in a spiffy new gated complex on the southern side of Kyiv and they moved in right in time for a baby girl to be born in October.

Now, speaking from the Kyiv condo, he weighs the risk of staying against the risk of getting his wife and infant out of the country, destination unknown. So far, the reason he has chosen to stay is because this second war feels different to him.

“In Donetsk, I felt the situation was hopeless, that nothing could be done,” he says. “Now, I feel like we’re on the brink of a huge historic moment and most of the world is behind us.”

Most of Mikhail’s friends and colleagues from Donetsk had also fled and resettled in other parts of Ukraine. One of them, Andrey, used to run the biggest business consulting firm in Donetsk. For him, becoming a pereselenets turned out to be an unexpected step up. He was able to move his business to Kyiv and grow it into one of the biggest consulting firms in the country with 150 employees. This time he says there is nowhere to move the business to. Their clients are all Ukrainian and their auditors and lawyers can’t work abroad.

“In 2014, I was lucky because I started working the first day after moving to Kyiv. It was easier for me than for my wife, who is a notary and didn’t want to restart her practice since we thought the conflict would end quickly and we’d return to Donetsk. This time, it’s harder because we both don’t work. We try to fill our day with small acts of kindness and that helps keep us distracted.”

Another friend of Mikhail, Yelena, fled from Donetsk with her 5-year-old son as soon as she heard the first blast outside the city in the spring of 2014. Someone had invited her to Izyum, a small town north of Donetsk, where they helped her find an apartment and get a job at a local school. Eight years later, it was in that school’s basement that Yelena and her now 13-year-old son were hiding with 200 other people when it was bombed and the building collapsed on top of them. Luckily, everyone was able to get out safely. However, Yelena fled from Izyum the next day. Speaking from Frankfurt where she is staying at a hotel that provides free lodging and food for refugees, she says she now needs to again figure out her future.

“I really hope to see my future in Ukraine,” she says. “I would love to return to Donetsk as soon as it’s flying a Ukrainian flag.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com