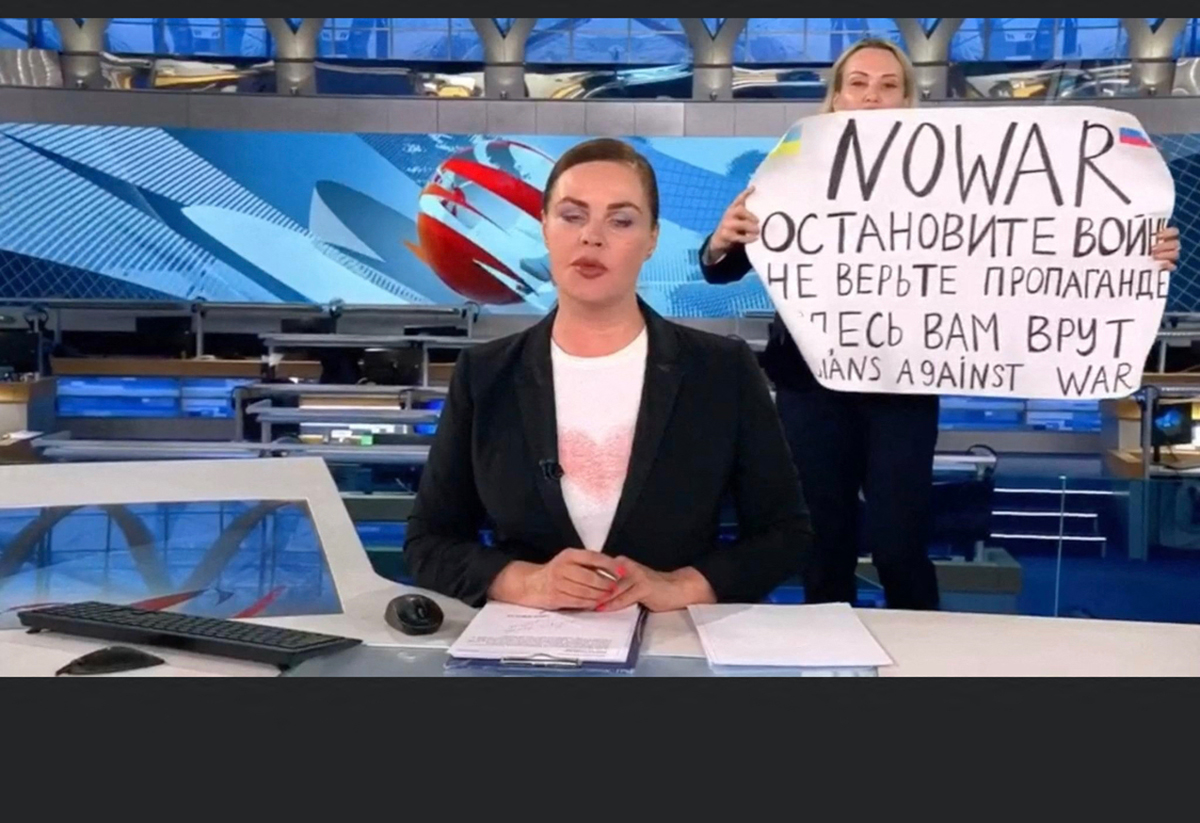

It was coming up on five a.m. and we were still at the casino. Our hotel in Lviv boasted a basement filled with card tables, slot machines, and a full-sized roulette wheel, which is where my friend and I sat, waiting out that morning’s air raid. On our first night we had commented on the absurdity of sitting through an air raid at a roulette wheel. Now, exhausted from yet another night of interrupted sleep, we silently watched the news on an enormous flat screen. In better times this television had broadcast horse races, soccer, boxing; any other contest on which a person might gamble. Today, it was the news. Marina Ovsyannikova, the Russian journalist who’d interrupted a government sponsored broadcast to hold up a sign protesting the war in Ukraine, was the lead. In the hour I watched, three or four hopeful segments mentioned Marina Ovsyannikova. Then the air raid app on our phones squelched the all-clear. Sluggishly, we climbed the stairs to our rooms.

Matt, a serial entrepreneur and my companion on this trip, had started businesses in Turkey, Syria, and Afghanistan, and he had recently finished a stint at Yale’s Jackson Institute of Global Affairs. A one-time collegiate rower, he had driven a trailer from Germany to Iraq at the height of that country’s war to deliver sculls to the Iraqi rowing team. A Farsi speaker, he’d also studied in an exchange program at Tehran University, which he failed to complete after the Iranian authorities accused him of espionage and imprisoned him for 41 days in 2015. He was released as a concession to the Obama Administration during negotiations around the nuclear deal. After the air raid, Matt suggested we meet Andrii, a tech entrepreneur and friend, so we stepped around the corner from our hotel for a coffee.

Andrii appeared haggard. Like a parent with a newborn, he calculated the days since he’d enjoyed an uninterrupted night’s sleep. He settled on a number around twenty as we reached the front of the line. Andrii ordered coffee as we settled at our table while Matt—who speaks decent Russian—confessed his fear that if he tried to order with the little Ukrainian he knew he might fumble and inject an unappreciated Russian word or phrase. Blond-haired, blue-eyed, Matt could certainly pass for Russian and, with Ukrainians actively hunting for Russian saboteurs, I could understand his concern.

“If you get in trouble,” Andrii explained, “just say: palyanytsia. Whoever is bothering you should then leave you alone.” He repeated this, carefully annunciating each syllable. He explained that a correct pronunciation would always bedevil the native Russian tongue. Both Matt and I tried, but Andrii remained unconvinced. “Perhaps English is best for you guys.” When I asked what palyanytsia meant, Andrii explained it was a kind of flat bread and very tasty, too.

I laughed, but Andrii didn’t seem amused. I apologized, explaining that it just seemed like a funny method to round up Russian saboteurs. Also, it seemed some Russians had chosen to stand with the Ukrainian people, so perhaps this was counterproductive. To emphasize my point, I mentioned Marina Ovsyannikova and her interruption of the nightly news. Andrii cut me off. “Do you think she’s a hero?”

“I think she’s brave.”

“She was fined 30,000 rubles, that’s less than 300 dollars. She was then immediately released. Are we really supposed to applaud her even though until a few days ago, she was happy to dispense propaganda while Russia waged its war?”

The war was only a few weeks old, and I remarked that sometimes it takes people time to find their conscience. Andrii could hardly contain himself. “Really? A few weeks old? Don’t forget, this war has been going on since Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, or at least since it took the Donbas in 2014. Should it take eight years to find one’s conscience?”

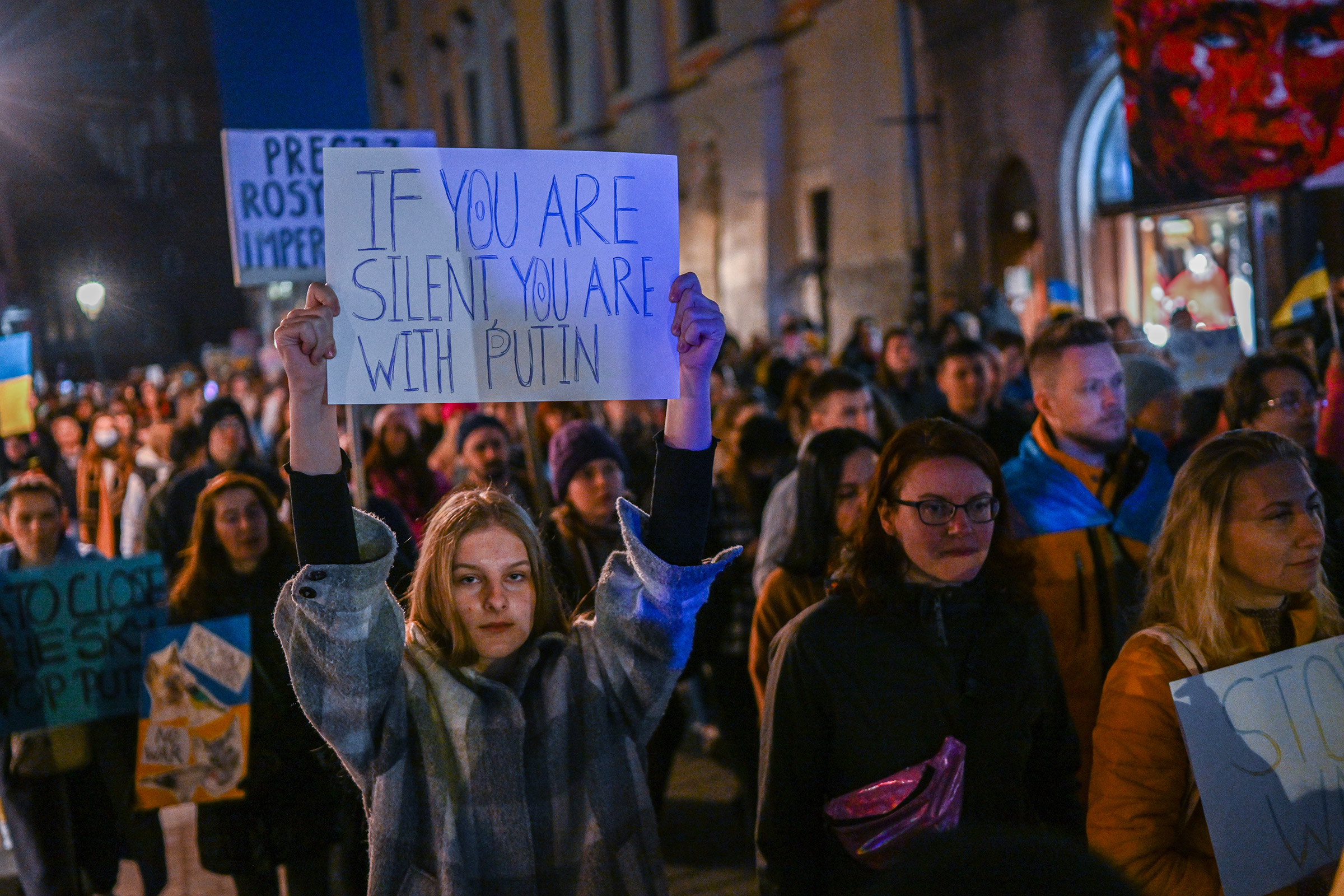

For Andrii, a narrative that categorized the Ukrainian and Russian peoples as victims of Putin’s war absolved Russian citizens of decades of complicity. “I am sick of reading media stories pitying liberal Russians emigres who’ve fled to Helsinki or to Istanbul to work their tech jobs remotely as they cry about their devalued rubles. Their complaint is always that they have no future in an authoritarian Russia, not that a genocide is occurring inside Ukraine. They say Stop the War. The don’t say Save Ukraine. They would be happy to see Ukraine annexed into Russia. It’s only the means of that annexation they object to, a method of war that has made them pariahs. The end in Ukraine is fine with them, just as it was fine in Crimea, in Georgia, and in Chechnya. Did any of them leave Russia after those successful invasions? No, of course not. It’s failed wars they’re against, not Ukraine they’re for; there’s a difference.”

The atmosphere between us turned tense.

“Palyanytsia,” said Matt, trying again with great effort.

Andrii relaxed with a smile. “That’s better,” he said. “Now you’re getting it.”

The next morning, Matt and I sat at the roulette wheel awaiting the end of an air raid. The attack from the day before had struck the Lviv airport, and while I wondered where today’s rockets might land, the word genocide, which Andrii had used the day before, troubled me. I had often been taught that people who live under autocratic regimes are never the enemy; rather it’s the regime itself. This theory seemed to be driving our Western strategy of sanctions, one designed to place domestic pressure on Putin and perhaps even cleave the Russian people away from him. Indeed, our entire Western strategy seemed to hinge on two variables: the resolve of the Ukrainian people to endure and fight; and the resolve of the Russian people to resist and reject Putin. If either faltered, the Ukrainian people would be subjected to genocide, a term often used in hyperbole, but the definition of which fit: “the deliberate and systemic destruction of a racial, political, or cultural group.”

Read More: A Ukrainian Photographer Documents the Invasion of His Country

Putin has been open about his desire “to solve the Ukrainian question.” This summer, in a lengthy essay published by the Kremlin, he denied the existence of an independent Ukrainian nationality and also claimed that Russians and Ukrainians are one people—a Russian people. And if Putin is engaging in genocide, are everyday Russians complicit? While polling inside Russia is unreliable, multiple independent polls show strong majority Russian support for the war in Ukraine. So if a majority of Russians support the war is a Western strategy that relies on internal Russian pressure against Putin fundamentally flawed?

Time will tell.

In a conflict already echoing the Second World War, it would seem we are wishfully projecting our sentiments onto the Russian people. If Ukraine—and the liberal Western order—can prove victorious in this war, perhaps we should be thinking of Russia like we thought of Germany in the 1940s. The decoupling of the Russian people from the regime that acts in their name is an exercise Americans and the West seem more interested in than Ukrainians, whose resolve against Russia remains incredibly high, with nearly eighty percent rejecting any territorial concessions, to include Crimea and the Donbas. And if the pronunciation session of rusni-pyzda with Andrii didn’t hit home this point, walking down the street in Lviv one need only glimpse the front of any currency exchange: the offered rate for rubles is 00.00, so worthless.

The next morning, we waited in the Vienna Coffee House for Yaroslav Hrytsak, a history professor at Ukrainian Catholic University and prominent intellectual, the author of the bestselling Global History of Ukraine. When Hrytsak arrived, he sat across from us, adjusting his chair as if preparing to deliver a lecture. His mask, which he’d pulled beneath his chin, served as a hammock for his ample, grey beard. “This coffee house,” he announced, “is the oldest in Lviv.” He held his index finger to the bridge of his nose. “It is worth noting that the oldest coffee house in Lviv is named the Vienna Coffee House, while the oldest coffee house in Vienna is named the Lviv Coffee House. That is a good first lesson in eastern European politics and culture.”

Hrytsak, like Andrii, believed it wasn’t possible to decouple the war in Ukraine from the Russian people. When I asked if he could explain why, he peered over his reading glasses and took a breath; it was as if I’d arrived in the last fifteen minutes of a three-hour movie and asked him what it was about. With patience, he replied: “No one feels Russian identity more than Ukrainians. You see, the Russian identity is a spiritual one, in which Russia believes it is the savior of the world.” When I asked what Russia had to save the world from, Hrytsak replied, “The West, of course. Right now, Putin isn’t fighting Ukraine. Remember, he’s fighting Nazis and Nazism is synonymous with the West. In Putin’s mind Ukraine does not exist; it is a fiction, a creation of the West, one he must destroy. Embedded in Russian identity is a belief that it has a special mission to fight the West. From Napoleon to Hitler, Russia is the one that saves the world from the West and its depraved fascist tendencies. Russia defeated Napoleon. Russia defeated Hitler. And Putin will defeat Obama and Biden.”

“Obama?” Matt asked. “He’s not even in office.”

“As I said, this isn’t a rational war, it is a spiritual one.” Hrytsak sipped his coffee, gathering his thoughts before he continued, “Over five hundred years there have been many attempts to emancipate Russian society. Every attempt collapses with a ruthless autocrat. Why do the Russian people choose unfreedom? The answer is Russian culture. If Russia is indeed the savior of the world, that would mean its suffering has meaning, that its suffering is synonymous with its piety. That’s why the sanctions won’t work. Could you convince a Christian to become godless by making him suffer? No, of course not, his suffering only draws him closer to God. Russia has enjoyed periods of freedom, but always it returns to this condition of suffering. It’s important to understand that it’s not Putin who took Russia, but rather Russia which gave itself to Putin, and Putin has used Russia’s history of suffering to consolidate his power.”

Read More: How Volodymyr Zelensky United the World

Hrytsak folded his arms. “This city has been Austro-Hungarian, Polish, and Russian. The Poles in particular have a very strong claim on Lviv, but their culture is different than Russia’s. They have the ability to rethink the past, while Russian culture has a tendency to relive the past. In the one case, it’s like driving car with a small rearview mirror you can reference. In the other case, it’s like driving a car with your windshield coated in mud. All you can do is look out the back window.”

The Third World War, according to Hrytsak, had already begun. Russia, like Germany at the end of the First World War, had suffered a humiliating defeat at the end of the Cold War. He used the term “Weimar” to describe Russia’s post-Cold War government in the 1990s. He noted how Putin, like Hitler, mined nuggets of grievance out of a selective, flawed interpretation of history, then refined those grievances into political power, enough power to sell this narrative we were seeing now, one in which Russia would liberate brother Ukrainians from their Nazi government led by a Jewish president. “We don’t like being called brothers,” Hrytsak said, “by people who murder us.”

When I asked Hrytsak what, if anything, could break this spell, he explained, “The Russian people have made a bargain with Putin, and it’s one they’ve made throughout their history. They have allowed a despot to take away their freedom, but in exchange he has offered them glory.”

That afternoon, as if to resolve this question of Russian complicity, Andrii arranged for us to have coffee with Melaniya Podolyak, a political consultant who runs a warehouse where she sends crowdsourced supplies to Ukrainian soldiers on the front. As we sat, she scrolled photos on her phone: sniper scopes; tactical vests; body armor; then the coup de grace . . . She played a video of a six-wheeled truck towing a howitzer into its firing position. “I bought that truck,” she said proudly. Blond-haired, petite, wearing bug-eyed glasses with lenses nearing the size of tea saucers, she leaned across the table. “Let me ask you a question.” She crossed her arms, revealing a half-sleeve tattoo. “How many Ukrainian speaking schools exist inside of Russia?”

When I guessed zero, she told me I was correct, and then recounted the story of Volodymyr Senyshyn, who’d tried to build one in Tula, outside Moscow. His plan to open a school ended in his murder, in front of his home, on a well-lit street. The cause of death: skull fracture, stab wounds to the right temple, penetrating wounds to the face. The police never found the perpetrators. Shortly thereafter his wife, Natalya Kovalyova, who was a member of the organization Ukrainians in Russia, was attacked and beaten so badly she wound up in intensive care. Also in her case the police never found the perpetrators. “This wasn’t last year, or after the second Maidan uprising in 2013, this was back in 2006.” I noticed the print on Melaniya’s olive drab t-shirt: three grey wolves, their teeth bared, charging forward from each of the Ukrainian trident’s prongs.

“The reason the Russians are here,” Melaniya added, “is we succeeded in getting our freedom after the Maidan, in 2013. They hate us for it.”

What about the possibility of a Russian Maidan, or colored revolution, what about acts of resistance like Marina Ovsyannikova interrupting the news, what about Russian opposition leaders like Alexi Navalny, doesn’t any of that matter?

“Navalny!” She spat the word from her mouth. She pulled up a Tweet on her phone; in it, Navalny wrote, It’s one thing if Putin killed Ukrainian civilians and destroyed life-critical infrastructure with full approval from the Russian citizens. However, it’s a whole different story if Putin’s bloody venture is not supported by the society. Melaniya wanted me to see a comment below the tweet: Navalny understands that every day of Russian silence is catastrophic. Not for the Ukrainian victims they don’t care about: for Russia.

Melaniya’s distrust of Navalny stemmed from the fact that he, too, was a Russian nationalist. He could wind up being worse than Putin, she suspected, because the West would celebrate him and turn a blind eye toward Ukraine.

Did she really believe that? Could Navalny really be worse than Putin?

“Whether it’s a colored revolution, or Navalny, or anything else, it’s already too late. No protest movement can undo their crimes against us. Over the last eight years of war, the Russian people have done nothing.”

Once again, I mentioned Marina Ovsyannikova.

“So what? Now some propagandist comes on T.V. with a sign and we’re supposed to thank her? She worked at Channel One for eight years . . . eight years!” Melaniya checked her phone, as if searching for an excuse to leave, or at least to talk about something else. “Listen, I know that sounds harsh. Maybe you can’t understand, or you think that I’m bitter toward Russians, or even unfair to them. I’m not. What I feel towards Russians isn’t hate; it’s indifference. I am indifferent to their suffering and believe the world should feel that way too. But you’re an American, maybe you can’t understand. In your country, life is about the pursuit of happiness. We don’t live that way here. Our life is about survival, it always has been, and that is the fault of one country.”

Read More: Mothers Return to Ukraine to Rescue Their Children

Outside, the air raid sirens whined. Our phones mimicked the sound with the app we’d downloaded. As we huddled in the coffeeshop, Melaniya assured us it had, “good and thick old walls.” While we waited for the all-clear, we spoke of other things, of her life before the war, her once-burgeoning YouTube channel and career as a political consultant. She joked that she was a “different kind of political consultant now.” Speaking to Melaniya it seemed clear that what she wanted to convey wasn’t anger toward Russia but rather a warning: as much we all wanted to believe the world had changed—through increased social, cultural, and economic connections—it really hadn’t. And this message wasn’t coming from her alone; it was also coming out of my pocket, where an app blared an air raid siren.

That evening, I had a meeting scheduled with Dmytro Potekhin, a journalist and one of the organizers of the 2004 Orange Revolution, which overturned the corrupt result of that year’s presidential election. If the Russian people were to mobilize, it would likely be in a color revolution like the one Dmytro participated in. He was on the phone with me from Kyiv, and like everyone else I’d spoken to, Dmytro wasn’t optimistic. “Do I think a colored revolution is possible in Russia? Perhaps. Theoretically Russia could be democratic, though historically it hasn’t happened.”

Dmytro explained how, in 2005 and 2006, he’d traveled to Russia and trained their dissidents in the strategies and tactics of non-violent resistance. So why had those dissidents failed in Russia? “The problem is cultural,” he said. “Russian culture expects a single leader. Other societies are flatter. They are not vertical, like Russia. Every time the Russians create a movement it evolves into a vertical organization, one with a boss on the top. Look at Navalny. He could have created a great anti-corruption movement, but instead a vertical organization was built around him. I tried to teach Russians to build decentralized networks, but always they built corporations with a boss on the top and officers in the regions. Once the guy on the top is detained and once the regional offices are raided, the organization is stopped.”

But Dmytro could see certain optimistic green shoots. “Putin has finally taken off his mask. The whole world now sees him for who he is. In 2014, when I was working as a journalist in Donetsk, I was detained and thrown in a concentration camp. They’re calling us Nazi’s but they’re the ones running concentration camps. That was eight years ago. Did the world care that they had concentration camps then? No, the world did not care. They started this war first to control Crimea, then to control the Donbas, now they want to control all of Ukraine. Will the world allow Russia to set up concentration camps in all of Ukraine?”

What about the Russian people and their complicity over these many years? What about figures like Marina Ovsyannikova and the hope for others like her, on which so much of the West’s strategy seems to depend, at least for now?

“I know many Ukrainians don’t trust her because she helped start the war. But it will take her and many others like her to help stop it. It’s great that such things happen, but the point isn’t to make heroes or villains of these people, the point is to stop Putin.”

Correction, March 25: The original version of this story misstated the Ukrainian word for flat bread. It is “palyanytsia,” not “rusni-pryzda.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com