I viscerally recall the first time I heard that there were at least 64,000 missing Black girls and women in the United States. It was 2019 and I was attending a symposium focused on Black girlhood. At that time, I didn’t know the total number of missing people in the U.S., but 64,000 felt alarmingly high. After a bit of research, I found out that Black women and girls comprised more than 30% percent of women and girls reported missing in the U.S. And yet, Black women and girls constitute only 15% of the U.S. female population. My suspicion about the number being disproportionately and disturbingly high was sadly correct. The data shook me to my core. I had no idea so many of us were missing. By 2021, the number was more than 90,000.

In the past year we’ve had a national conversation about “Missing White Woman” syndrome, the phenomenon of missing white women and girls being overrepresented in media coverage, and consequently, public outrage and investment compared to missing Black, Indigenous, and other women and girls of color. But it is something that many of us were all too aware of. Too few people outside of the loved ones of those missing, local community organizers, and a handful of Black-led organizations sound the alarm about this crisis. The erasure, silence, and lack of collective attention resounds as profoundly violent and yet another example of the vast chasm between who does and who doesn’t care about the lives and livelihoods of Black girls and women.

But it’s not just about the media coverage itself. As a society, we continue to fail at examining why nearly 100,000 Black women and girls are currently missing, thus failing to address the deprivation, marginalization, and criminalization they face. I identify these conditions as unlivable living, a Black-life-centered riff on gender theorist Judith Butler’s concept of unlivable lives, because far too many of us are relegated to a life predisposed toward premature death.

Read More: Why Are Black Women and Girls Still an Afterthought in Our Outrage Over Police Violence?

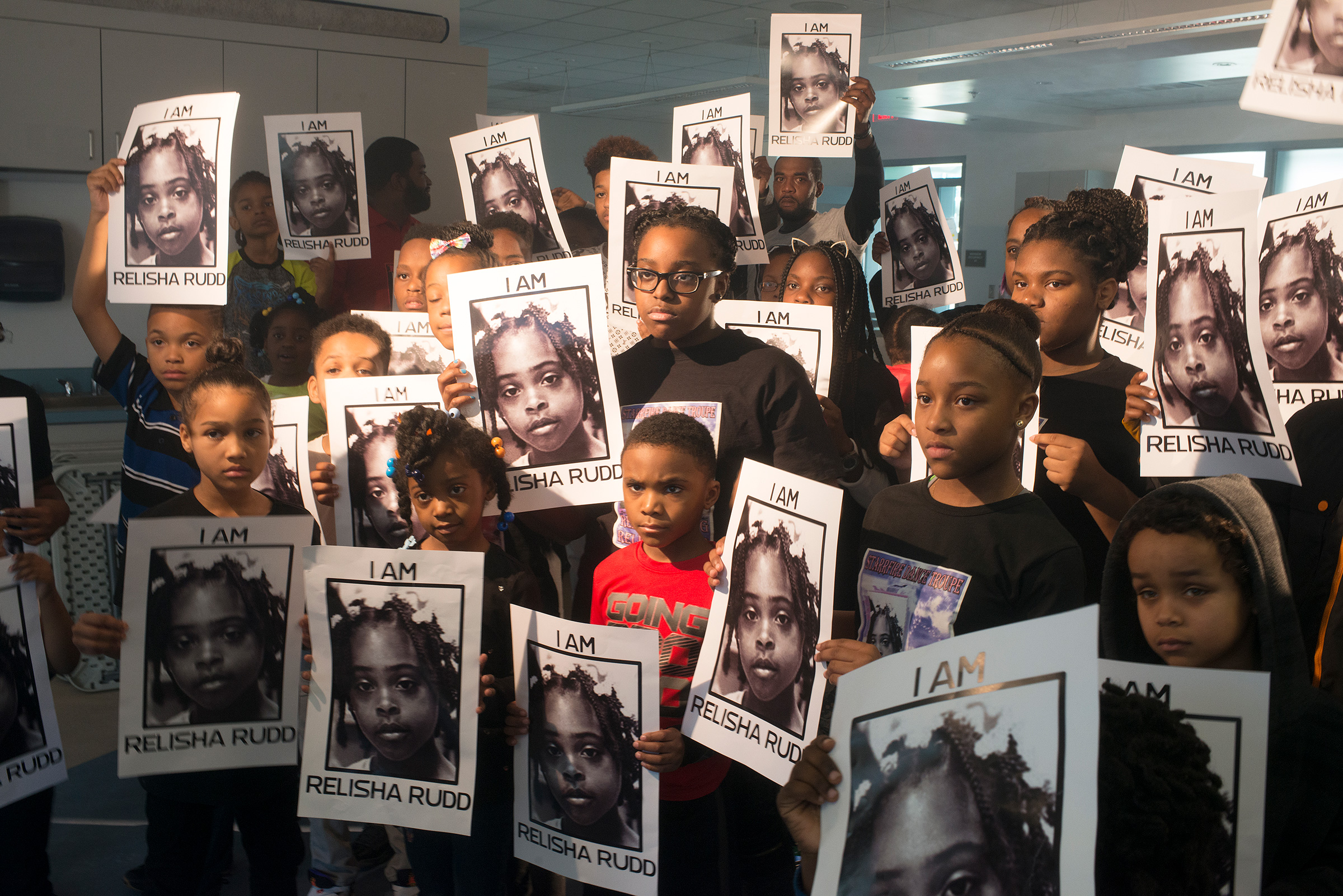

In 2017, I dedicated my first book, Colored No More: Reinventing Black Womanhood in Washington, D.C., about Black women who made the nation’s capital the country’s first major “Chocolate City,” to Relisha Rudd. She was an 8-year-old Black girl who disappeared in Washington, D.C. on March 1, 2014, and has never been found. I began my love letter to my hometown by Saying Her Name, a practice popularized by Kimberlé Crenshaw, Andrea Ritchie and the African American Policy Forum in an attempt to shed light upon violence against Black women and girls. It felt like the least I could do. I wanted her name alongside her D.C. foremothers, who would’ve fought for her and did fight to create a world in which Black girls didn’t go missing. Against all odds, I hoped one day Relisha would be found. Honestly, I still do. I fantasized about this little Black girl seeing her name in a book and knowing someone cared. I also thought that folks picking up my book would see her name and perhaps google her story. In the best-case scenario, the dedication would compel readers to Say Her Name too, even if only for a brief moment.

Every time I saw a picture of Relisha, tears would well in my eyes. She looked like she could be my kin. She lived close to my childhood home, too. When I was growing up, the homeless shelter in which she resided didn’t exist. The building was a part of D.C. General Hospital, which was founded as the Washington infirmary in 1806. The storied hospital, which was controversially shut down by former D.C. mayor Anthony Williams in 2001, provided de facto universal health care to uninsured, unhoused, impoverished, and marginalized D.C. residents. Growing up, I knew it as the hospital folks went to if they got shot or stabbed or had overdosed. It was triage for a community relegated to unlivable living.

To this day, conflicting reports abound regarding what happened in the weeks leading up to and immediately after Relisha’s disappearance. But there’s a good chance you haven’t followed this story, maybe haven’t even heard about it. While the investigation has been going on for years, the story of an 8-year-old Black girl who went missing never became a big national news story. In fact, it was barely covered outside the metropolitan area including D.C., Maryland, and Virginia, media outlets geared toward Black audiences, and social media posts.

In March 2021, Howard University graduate Jonquilyn Hill debuted a new podcast on WAMU 88.5 in Washington, D.C., titled Through The Cracks, in which she reexamined Relisha’s disappearance and the failures of multiple social safety nets in the life of this young Black girl. Last year Relisha’s story was also covered by Geeta Gandbhir and Soledad O’Brien in their four-part HBO series Black and Missing. I am heartened by the continued investment in unpacking the many truths of this vexing story. But I still await the day when we can fully answer the question: what happened to Relisha Rudd?

Words fail to capture the closeness I still feel to Relisha. Her story wasn’t exceptional per se in D.C. or in the U.S. more broadly, but it hit me exceptionally hard. Even as the worst-case scenario becomes more and more likely as years fly by, I can’t help but circle back to her. Amplifying the full stories of missing Black women and girls is one of our greatest tools in combating the perpetual harm to which we consign them, and I try to tell her story whenever I can.

Relisha’s story unveils many of the ways that nonspectacular, everyday injustices and inequities rooted in systemic and unrelenting deprivation slowly but surely erase or kill us. Thousands of us disappear without a trace. What is spectacular about this reality, nevertheless, is the frequency and consistency with which quotidian experiences with anti-Blackness, misogynoir, and capitalism manifest in our lives. Poor Black women and girls are unhoused, unfed, hypersurveilled, under- and unemployed, and viewed as expendable or valueless by those with the power to marginalize and criminalize. When you wear someone down, they become more susceptible to other forms of harm.

Relisha’s disappearance occurred within a web of death-dealing practices that affects tens of thousands of Black girls every single day. She encountered gross negligence and unenforced policies geared toward ensuring the well-being of residents at the D.C. General Shelter as well as the failure of agencies such as the Children and Family Service Agency to prioritize the welfare of poor Black families over the impulse to criminalize them. Systemically, she was victimized by decades of anti-poor, anti-Black, anti-family policies that ravaged poor Black communities in the nation’s capital and across the nation via the hypercriminalization of poverty and addiction.

What we ask girls like Relisha to survive is impossible. I suppose the lessening of any of the devastating death-dealing forces in the lives of Black women and girls could have helped her. There were just too many of them extant in her life. From the day she was born, she endured unlivable living. Anti-Blackness, poverty, and misogynoir situated this bright-eyed, gap-toothed, brown-skinned girl on the margins of the margins. It was only when something spectacular occurred—Relisha’s disappearance—that a woefully small number of people even came to know all the ways we failed her.

Adapted from America, Goddam: Violence, Black Women, and the Struggle for Justice

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com