There is absolutely nothing special about the star known to astronomers as 2MASS J17554042+6551277. It’s a nice bright star, yes—about 16 times brighter than the sun. And it’s located relatively close to Earth, as these things go—about 2,000 light years away. But it’s just one of up to 400 billion stars in the Milky Way, and until recently, nobody gave it a lot of thought.

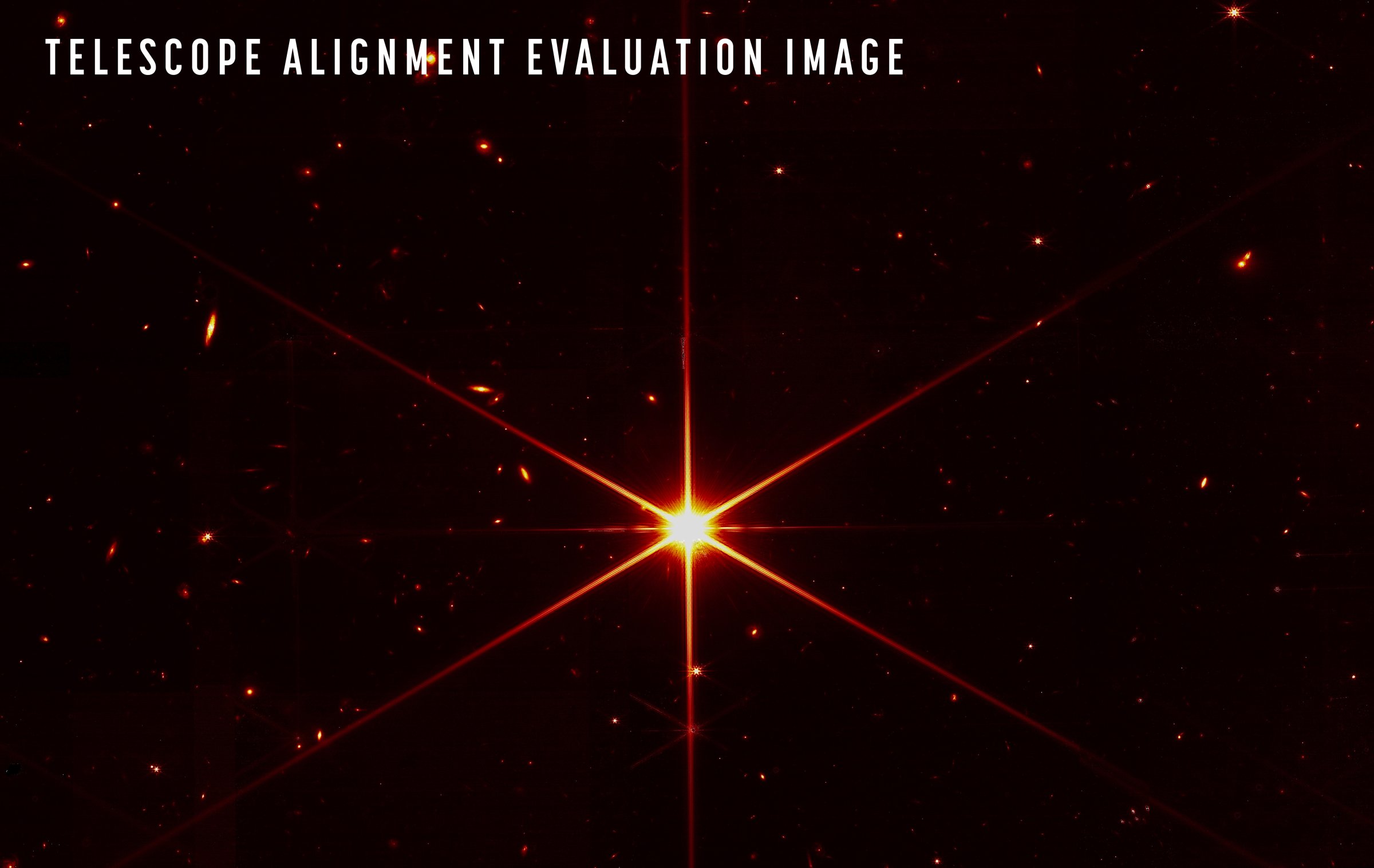

But late last week, 2MASS J17554042+6551277 became the most famous star known to science outside of our own sun. That’s because the James Webb Space Telescope—launched from Earth on Christmas Day and now located 1.6 million km (1 million miles) away—chose the ordinary star to take an extraordinary picture: its first image with its 18 hexagonal mirror segments in near-perfect alignment. As NASA, Inverse and others report, Webb captured the star with a red filter to enhance its brightness, and could see not only the stellar target itself but also stars and galaxies in the background.

“More than 20 years ago, the Webb team set out to build the most powerful telescope that anyone has ever put in space and came up with an audacious optical design to meet demanding science goals,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, a NASA associate administrator, at a press conference on March 16, the day the image was released. “Today we can say that design is going to deliver.”

Capturing the image took some doing. The 18 segments that make up the Webb’s 6.5 m (21 ft., 4 in.) diameter mirror are driven by actuators that allow them to move in seven axes. Each segment works as its own independent mirror—meaning that, left to themselves, they would capture 18 hazy images of a single body instead of one extraordinarily sharp one. Ground controllers have been working for months to align the segments to within a few nanometers—or billionths of a meter—of one another. The image of 2MASS J17554042+6551277 was taken when the mirrors had completed what NASA calls the “fine-phasing” stage of their alignment. That is close to the final stage of focusing, but not yet quite there yet.

Finer still adjustments will be taking place over the next several months, with the mirror segments still being tweaked at least through May. It will then take until the end of June or early July before all of the $10 billion telescope’s other instruments are calibrated and brought online. Only then will an observatory that has been in development for the past 25 years at last be ready to truly go to work.

“We are excited about what this means for science,” said Ritva Keski-Kuha, deputy optical telescope element manager for Webb, during the agency press conference. “We now know we have built the right telescope.”

This story originally appeared in TIME Space, our weekly newsletter covering all things space. You can sign up here.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com