In 1958, in response to an alarming uptick in xenophobic chatter, the Anti-Defamation League asked then-Senator John F. Kennedy to write about America’s melting-pot strengths and the need for immigration reform. The resulting essay, “A Nation of Immigrants”—published as a book after JFK’s death—popularized the idealistic phrase that’s been touted by politicians ever since.

America still likes to think of itself as a nation of immigrants, but even JFK admitted in print: the truth has always been more complicated. All four of his grandparents were American-born children of Irish immigrants who confronted “the hostility of an already established group of ‘Americans’,” wrote Kennedy. “It is not unusual for people to fear and distrust that which they are not familiar with. Every new group coming to America found this fear and suspicion facing them.”

The history of immigration in America is in fact the history of its nativist foes. (Not to mention the history of colonialism, the slaughter of Native Americans, and the enslavement of Africans.) We’re reluctantly and uncomfortably an inclusive nation; we’re a nation of immigrants despite a deep, dark history of efforts to keep newcomers out—or at least down.

Take the immigrant Kennedys. JFK’s paternal great-grandparents, Bridget Murphy and Patrick Kennedy, were the first to leave their respective County Wexford families, sailing in a crowded “coffin ship” seeking safer shores across the Atlantic. Landing in 1848 at the docks of East Boston, not far from Terminal A at today’s Logan Airport (named for the son of an Irish immigrant brewer), they met, married and started a family, but quickly discovered they were unwanted refugees.

They’d been oppressed in Ireland by their homeland’s colonizer—England had banned their religion and their native language; prevented them from voting and holding office; reacted slowly and indifferently when the Potato Famine of the 1840s led to mass starvation (a million dead) and mass migration (upwards of two million fled).

But in America? It turned out that the land George Washington had envisioned as “a safe and agreeable asylum” for “the oppressed and persecuted of all Nations and Religions” didn’t really want them, either.

As part of the first large wave of (mostly poor and rural) Irish newcomers to (mostly urban) America—25,000 arrived in Boston in 1848 alone, among the million who came to North America—the Kennedys experienced many of the 19th-century low points in the nation’s tolerance for the outsider: voter suppression, anti-immigrant legislation and voting efforts, riots at the polls, plus the mid-1850s rise of the nativist Know Nothing party, its hatred aimed mostly at Irish and Catholics.

In their immigrant-crowded East Boston neighborhood, Bridget and Patrick Kennedy and their children and neighbors witnessed violent protests outside their homes, their church, their businesses. They looked out the window at parades of young men marching with faux-patriotic groups like the Order of Free and Accepted Americans, the Order of the American Star, the American Protestant Society, and the Wide Awakes, threatening the Irish with their angry chants, “Wide awake! Wide awake!” Backed by their right-wing newspapers and magazines—the Republican, the Protestant, the Spirit of ’76—their mantra: “Americans must rule America.”

Boston had been a hub of anti-slavery activism, but otherwise it was hardly a model of integration or tolerance. Take Boston artist and inventor Samuel F. B. Morse, who helped create the telegraph and Morse code. Though he later said his invention aspired to make “one neighborhood of the whole country,” Morse’s electromagnetic dots and dashes were originally designed as a secret code that could be used to defeat a rumored plot to make “Popery” (Catholicism) the law of the land.

A well-known anti-immigrant, pro-slavery activist, Morse’s 1835 book, Foreign Conspiracy Against the Liberties of the United States, called for limits on immigration from Catholic countries and for banning Catholics from holding public office. He unsuccessfully ran for mayor of New York as candidate for the Native American Party (later known as the American Party, and generally known through the mid-1800s as the Know Nothings—its members claimed to “know nothing” about it. John Wilkes Booth was an adherent, as was Ulysses Grant’s vice president, Henry Wilson.)

Morse and the Know Nothings were among many voices roaring against nineteenth-century immigrants, their words and actions eerily familiar to those of recent years. Xenophobia had become an “American tradition,” as Erika Lee put it in her 2019 book, America for Americans.

Clearly, not much has changed over the centuries. We’ve always tried to prevent immigrants (and minorities) from access to the ballot (and to citizenship, and to power).

Today, the street corners of the Kennedys’ East Boston neighborhood are anchored by bodegas and Latin markets. Those startup businesses, many run by immigrants from Brazil and Mexico, replaced the Italian delis that in turn had replaced the Irish grocery shops like the one JFK’s great-grandmother Bridget ran for twenty years after the Civil War—and the Irish saloons like those that helped launch the late-1800s political career of Bridget’s son, P.J..

A microcosm of newcomer entrepreneurism, East Boston continued to reflect an increasingly immigrant rich nation. Recent census data shows that while 2021 had the slowest population growth in U.S. history, growth attributed to immigration contributed to an uptick in the percentage of Americans born elsewhere. Immigrants now represent 14.1 percent of the U.S. population, inching closer to the all-time high of 14.8 percent, which was reached in 1890.

Then as now, immigrants came despite the efforts of men like Henry Cabot Lodge, a longtime Massachusetts statesman who through the 1890s called on voters to “guard our civilization against an infusion which seems to threaten deterioration.” Lodge railed against “hyphenism,” preferring “100 percent Americanism” to Irish-American or Italian-American designations.

When Lodge ran for the U.S. Senate in 1892, his support for strict immigration limits and a proposed federal literacy test for newcomers helped him defeat Irish Congressman Patrick Collins, whom Lodge decried as “hard-drinking, idle, quarrelsome, and disorderly.” Many of Lodge’s nativist ideas, including the literacy test, were later incorporated into the Immigration Act of 1917.

On the Fourth of July, 1895, the American Protective Association, an anti-Catholic group, paraded through East Boston ranting about Irish “aliens” and “enemies of the state.” Riots ensued and shots were fired and an immigrant longshoreman was killed, dying on the steps of P.J. Kennedy’s saloon. P.J. invited his friend, the newly elected Congressman John F. Fitzgerald, to come to East Boston and calm things down. At a fundraiser for the murdered longshoreman, Fitzgerald addressed the “intense hatred of everything Irish and Roman Catholic” that persisted, and blamed radical, secretive men’s groups for trying to “monopolize all the Americanism in this country.”

“We are one people and owe the same duty to our country,” Fitzgerald told the crowd. “Why, then, this desire to set one class of people against another?”

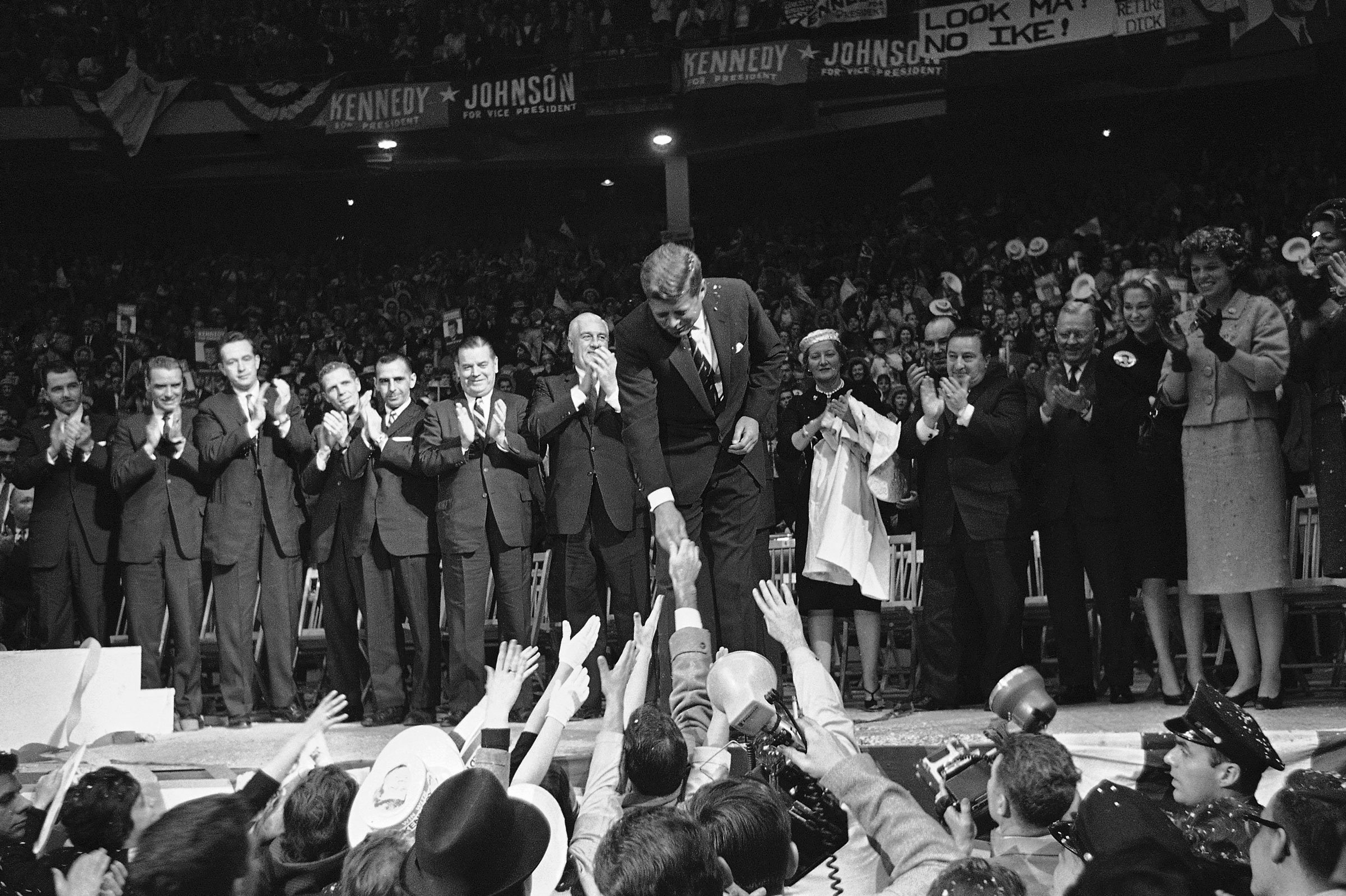

Decades later, the grandson of P.J. Kennedy and “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald defeated the grandson of Henry Cabot Lodge, and midway through his Senate term JFK penned his hopeful views on the subject of Americanism: “There is no part of America that has not been touched by our immigrant background,” he wrote. Kennedy also lobbied in A Nation of Immigrants against a quota system that favored the Northern and Western European countries of his ancestors, and discriminated against immigrants from Asia and Africa. (That national origins quota system was ended by the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965.)

The 35th president clearly had very different views than those of the 45th president, the son, grandson, and spouse of immigrants, who infamously declared his preference for more immigrants from “places like Norway” and fewer from “shithole countries.” (And whose influence led to the removal of the words “nation of immigrants” from the mission statement of the U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services.)

Champions of immigration have always faced the build-a-wall fervor of former President Trump’s base. As Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz put it her 2021 book, Not A Nation of Immigrants, the ideology of JFK’s “nation of immigrants” premise is flawed—and under constant assault.

The fear-mongering of the Morses, Lodges, and Trumps of America will continue to try to shout down the hopeful words of its Kennedys and Obamas. “In no other country is my story even possible,” the nation’s first Black president once said, echoing the optimism of George Washington, who wrote: “I had always hoped that this land might become a safe and agreeable asylum to the virtuous and persecuted part of mankind, to whatever nation they might belong.” Then again, America’s first president was a slaveholder whose ideals on asylum clearly didn’t apply to enslaved Africans. It’s complicated.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Introducing the 2025 Closers

Contact us at letters@time.com