The last few weeks on the campaign trail have been a blur for Jang Hye-yeong, a lawmaker in South Korea’s progressive Justice Party. But amid the flurry of train rides and stump speeches to support her party’s long-shot presidential candidate, Sim Sang-jung, Jang says one moment stood out.

A former labor activist and the only woman from a mainstream party who ran in South Korea’s presidential election, Sim addressed a crowd in Seoul last week. Jang watched a young woman excitedly pull out her phone to film. But a man, whom Jang believes was the woman’s boyfriend, snatched the phone out of her hand, and dragged her away by the wrist.

Jang, 34, doesn’t know for sure what happened between the couple, but as she worried for the woman’s safety. She could also not help but see the moment, and the presidential election, as emblematic of the state of gender equality in South Korea. Modest gains by women in recent years have sparked an anti-feminist backlash, in which disgruntled young men have become vocally critical of feminism and women who speak out.

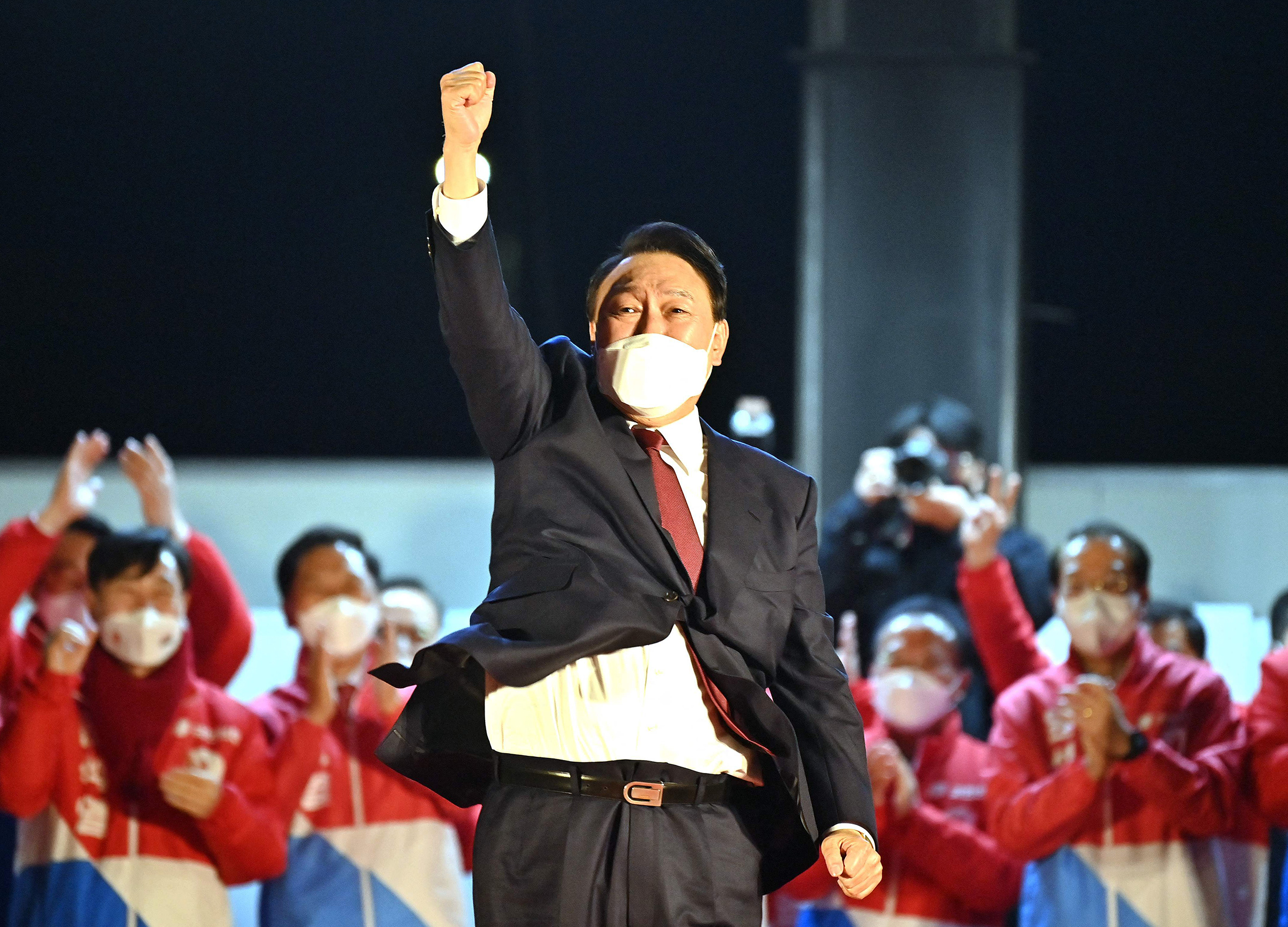

No candidate capitalized on the anti-feminist movement like Yoon Suk-yeol, who narrowly won Wednesday’s election and will become South Korea’s next leader. The populist, from the conservative People Power Party (PPP), worked to appeal to men who are anxious about losing ground to women, and helped turn a fringe online community into a major political force.

Yoon called for the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family to be abolished, and accused its officials of treating men like “potential sex criminals.” He has blamed the country’s low birth rate on feminism—saying that feminism prevents healthy relationships between men and women. He also said that he doesn’t think systemic “structural discrimination based on gender” exists in South Korea—despite Korean women being at or near the bottom of the developed world in a host of economic and social indicators.

According to an exit poll conducted by three South Korean broadcasters, some 59% of men in their twenties, and 53% of men in their thirties, voted for him. Just 34% of women in their 20s supported him.

“Anti-feminist sentiment was widely used to gain voters in the election,” says Lee Ye-eun, of the feminist group Haeil. “It was even the main strategy.”

How anti-feminism became a political force

Both leading presidential candidates incorporated at least some anti-feminist rhetoric into their campaigns in an attempt to attract young men.

Lee Jae-myung, who represented President Moon Jae-in’s Democratic Party of Korea (DPK), campaigned on a platform of fixing social inequalities through progressive policies like ensuring that at least 30% of top officials are women. In a Mar. 1 interview with TIME, he criticized Yoon’s contention that gender equality wasn’t systemic. “I think it’s very important to acknowledge the inequalities and issues of gender inequality that women suffer structurally in our society,” he said.

But even Lee has said that he opposes “discrimination” against men. Although he is against Yoon’s plan to abolish the gender equality ministry, he has called for the government agency to be revamped.

Women say they worry that the anti-feminist language used by such high profile figures will normalize the movement—and further marginalize women in South Korea.

A combination of rampant economic inequality, slowing growth, and some of the most patriarchal social dynamics in the developed world managed to turn gender equality into a polarizing election issue. “[The main candidates] are kind of messaging their whole campaign to speak to this very disgruntled population of young men who feel like they’re being left behind,” says Sharon Yoon, an assistant professor of Korean studies at the University of Notre Dame.

At a polling station in Incheon, a city of three million just outside Seoul, Seo Jae-sang, 28, told TIME that gender equality was only third or fourth on his list of political priorities. First was South Korea’s increasingly unaffordable housing market—the average price of an apartment in Seoul has more than doubled in the last five years, to about $1 million. But he agrees with Yoon Suk-yeol that the gender equality ministry should be dismantled because it is “escalating gender issues.”

READ MORE: The South Korean Presidential Hopeful Who Believes His Childhood Can Help Him Heal His Nation

Some experts caution against attributing too much of Yoon’s victory to his anti-feminist campaign promises, especially given the razor thin margins. Yoon claimed 48.6% of the vote, and Lee won 47.8%. The campaign was also marked by mudslinging and misconduct. Lee’s wife allegedly used his staff to run personal errands, and Yoon has faced questions over his unscientific beliefs, including the use of a shaman and an anal acupuncturist (which he has denied). Many voters were also frustrated with Moon, who is barred from running for a second term by the constitution, for failing to curb surging property prices. His term was also beset by corruption scandals, including local officials using insider knowledge to invest in real estate.

The Notre Dame professor Yoon says that it appears from exit polls that both men and women in their twenties were more concerned about picking a candidate who would improve their economic standing, than gender issues. “The sharp divide among men and women in their twenties is striking,” she says. “It is unclear whether men voted for Yoon because they resonated with his anti-feminist rhetoric, or because they were concerned about the real estate scandals that have tainted Moon’s legacy.”

Other political commentators say that the victor’s anti-feminist tactics backfired. “It seems like women who would have voted for Sim [a third-party candidate] might have voted for Lee,” closing the gap between Yoon and his closest rival, says Young-Im Lee, who specializes in gender and elections in East Asia at California State University (CSU), Sacramento.

The ‘feminism reboot’ has that challenged South Korea’s patriarchy

Although a record 57 women were elected to parliament in the last election in April 2020, they still make up a woeful 19% of lawmakers. (The U.S. Congress currently has 27%). In the business world, women hold few positions of power on boards, and the country has the highest gender wage gap among wealthy countries—with women earning 31.5% less than men. More than half of homicide victims in South Korea are women—one of the highest gender ratios in the world (the global average is about 21%). Sex crimes are rife. In the recent “Nth Room ” case, at least 74 victims, including underage girls, were blackmailed into uploading explicit videos of themselves on Telegram by a man nicknamed “God God,” who then sold the images.

But, women are increasingly fighting back. The 2016 murder of a 23-year-old woman in the ritzy Gangnam neighborhood—in a random attack by a man who said “he hated women for ignoring him”—sparked an outpouring of rage and the so-called “feminism reboot.” The surge of interest in gender equality for women set the stage, in 2018, for South Korea’s #MeToo movement, which brought a wave of women speaking out against film directors, politicians, and actors. Under banners that read: “My Life is Not Your Porn,” women also took to the streets en masse to protest the use of spycams prompting a crackdown on the use of illegal cameras in public places.

But the increasing visibility of feminism and the fight for gender equality has been met with a growing backlash from some men who think the movement has caused “reverse discrimination” and that #MeToo is a witch hunt. In a June 2021 poll, 84% of Korean men in their twenties, and 83% in their thirties, said they had experienced “serious gender-based discrimination.” (In a survey March 2019 U.S. survey by the Hill-HarrisX, 38% of Democrats and 56% of Republicans surveyed said men faced discrimination).

“The unemployment rate is high, housing prices are really high. So, men in their twenties start to feel like ‘we are the victims,’ says Lee at CSU. “They need something to blame those problems on and anti-feminism is a channel to vent their frustration.”

In an early sign of how polarized the debate over gender equality was becoming, the 2019 movie adaption of the bestselling book Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982—which details the every day gender discrimination faced by an average South Korean woman— led couples to argue, and some to break-up, according to media reports.

The anti-feminist movement has incubated in online forums, where some men have been radicalized. “Spy cam? It has to be punished sternly by law. But the Republic of Korea is now going crazy, scrapping the principle of benefit of doubt by letting men be branded as sex criminals without any evidence just because women say so, due to the feminist establishment,” Bae In-gyu, a central figure of the anti-feminist group “New Men on Solidarity,” wrote last month on Facebook, where he has more than 15,000 followers. (Bae did not respond to TIME’s request for an interview).

Jang, the South Korean lawmaker, faces vicious trolling online. She tries not to read the online attacks against her, but “as a politician I can’t just cherry-pick people’s reactions, so sometimes I have to read these things. Sometimes it makes me need a drink,” she says, laughing.

But her smile fades as she talks about how the anti-feminist sentiment has become so extreme that she worries about her physical safety. She says the abuse has impacted her mental health. Bae’s group has held numerous protests against feminists. Several feminists TIME spoke to said they receive frequent threatening phone calls, and have been physically attacked, including having water thrown on them merely for having short hair. “After anti-feminism gained traction, more people are beginning to accept violence against feminists, like, ‘they’re feminists and they deserve it.’ This is gravely dangerous,” Jang says.

Anti-feminists have targeted women across South Korean society. Olympic archer An San won several medals at the Tokyo Olympics, but she received online abuse at home for her short hairstyle. “We didn’t train and feed you with tax money so that you can commit feminist acts,” one man posted.

A suicide prevention website aimed at young women, whose suicide rates jumped by more than 40% during the pandemic, even went down temporarily because of attacks by hackers who said it disregarded men’s lives.

In August 2021, Bae reportedly dressed as the Joker and harassed women’s rights activists from the feminist group Haeil at a rally for a video for social media. “I heard that there were f—king feminists here; I’m going to murder them all,” he reportedly said.

READ MORE: How #MeToo Is Taking on a Life of Its Own in Asia

‘A lonely time’ for feminist politicians

Although women across South Korean public life have reported regularly being the target of misogynistic attacks, female politicians come in for some of the worst abuse. The Justice Party’s Ryu Ho-jeong, 29, is South Korea’s youngest lawmaker, and a fierce advocate for workers rights. But she has also spoken out on gender equality issues, and in August 2020 she wore a casual summer dress to the National Assembly, sparking national media coverage and drawing criticism from social media users and even some politicians.

Ryu highlighted some of the most vitriolic comments she’s received with a Facebook post in May 2021, the one year anniversary of her term, including 18 full-page screenshots of online abuse.

“You piece of s— b—…live stream your t—s, you dirty feminist b—,” read one comment. “Is this a lawmaker or someone working at a bar, LOL,” another wrote, in response to a photo of Ryu wearing a dress that would be considered perfectly respectable in most other countries. Others called her a “call girl.”

“The trolling, the attacks—of course, it doesn’t make me feel good, but there are a lot of women I represent that suffer worse harassment or discrimination than I do. There are people who I should stand up for. That’s what makes me keep going,” Ryu tells TIME, while on a train from the city of Daejeon to Daegu. She’s also been campaigning non-stop for the past few weeks for the Justice Party’s Sim.

Jang also faces vicious online trolling. Although she’s best known for her work on disability rights, she publicly identifies as a feminist. She says that as the result of the backlash against feminism, it’s hard to find other politicians who will talk about feminist issues or label themselves as a feminist. “It’s a rather lonely time,” she says. “A friend of mine told me that I have to stand like a bulwark. ‘No matter the weather or how many harsh waves hit you and try to tear you down, you need to stand strong against this backlash.'”

But she worries that anti-feminism may have serious implications for her political career. She cares deeply about things like rights for disabled people and climate change, but she fears that being positioned as a feminist politician in a “male-centric and deeply patriarchal political environment” is the “new glass ceiling in politics.” “Whatever you say is considered to be just another feminist plot,” she says.

A president who espouses anti-feminist sentiments

Even before the election, the possibility of a Yoon presidency had some women worried about what their future might look like. Kim Ju-hee, one of the co-founders of Haeil, thinks Yoon’s tactics are similar to those used by former U.S. president Donald Trump, who stoked hatred to win voters—except that Yoon is targeting women instead of immigrants. She worries that attacks on feminists will get worse like attacks on minorities did in the U.S.

“After Trump’s election, immigrants were in more danger. I worry the same will happen [to women] in South Korea after a conservative victory,” she says.

One woman in her early thirties, who asked not to be named because she didn’t want to publicly share her voting preferences, tells TIME after Lee conceded the election Thursday, she was “super devastated.”

She had stayed up all night watching the election results roll in with a group of friends. “[Yoon] is the definition of hatred and it’s not only about gender equality. He won this election based on hatred against all kinds of minorities, not just women.”

She told TIME that gender equality was the number one issue for her heading into the polls. She loves the Justice Party’s candidate Sim and initially planned to vote for her despite the fact that Sim had no shot at victory. (Like the U.S., presidential politics in South Korea is dominated by two main political parties, and third-party candidates don’t stand a chance of winning the election).

But the woman had noticed that Lee has been more vocal about women’s issues recently, and she wanted to do what she could to keep Yoon from getting elected. “I can’t live in this country with a president that doesn’t think structural discrimination exists.”

No matter the result, many women say that the anti-feminist rhetoric that has defined this election campaign has made South Korea a worse place for them. “It’s really detrimental to South Korean politics,” says Jang. “I believe that the citizens’ lives are worsening as anti-feminist rhetoric is being explicitly accepted in the public sphere, including politics.”

—With reporting by Subin Kim/Incheon, South Korea and Charlie Campbell/London

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Putin’s Enemies Are Struggling to Unite

- Women Say They Were Pressured Into Long-Term Birth Control

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- Boredom Makes Us Human

- John Mulaney Has What Late Night Needs

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Amy Gunia at amy.gunia@time.com