Living organisms have been colonizing the planet for nearly four billion years. They’ve taken on countless forms through assorted evolutionary and adaptive mechanisms to survive in environments where conditions are highly specific and always changing. One of the most striking aspects of animals that have evolved to reproduce by means of internal fertilization is the morphological diversity of the genital organs. Remarkably, in species with little variation in terms of general morphology, the differences between the genitals of males (which have received more attention from researchers than those of females) are considerable.

It seems that multiple reasons underlie this impressive evolutionary development, and the questions that remain unanswered are stimulating. What purpose does the penis serve? Why is it that members of one species have no penis at all, while those of another have two? Why do they vary so much in shape and size? And where do vaginas, or the clitoris, fit into all of this? What about pleasure? Does such a thing even exist in the animal world? If so, what forms does it take?

The mechanisms involved are complex. To have any chance of understanding them, we need to look at how these organs evolved. That means going back more than 400 million years, to a time well before dinosaurs walked the earth. Until this point, fertilization was essentially external: females expelled their eggs into the water, and males did the same with their semen. But when certain marine creatures emerged from the water, their bodies had to adapt to their new environment. Genitals included: external fertilization won’t work if males—and females—launch their sex cells into the air or onto the earth; the biological material doesn’t survive for long. Reproduction demanded a real innovation in anatomy so that life could thrive on terra firma. That’s where internal fertilization comes in: the female keeps her eggs inside her body, and the male adds his semen.

When it comes to passing on one’s genes, the competition is fierce, both between individuals of the same sex and between males and females. As a result, various species have developed assorted strategies for reproduction, from new organs to outright war between the sexes that culminates in the self-sacrifice of the male. The animal kingdom holds countless surprises in store. Such strategies are at the root of striking differences in genital form and function.

What follows are just a few examples of the most improbable—at least by human standards—examples of how animals’ bodies, behavior, and genitals in particular, have adapted to meet their own reproductive needs in their own little terrestrial niche.

THE WATER BOATMAN (Micronecta scholtzi)

The water boatman is a two-millimeter insect common in freshwater ponds across Europe. It is unprepossessing in every way—save for one. The males of this species attract females by singing. Fine, you might say, they’re not the only ones who do so. True, but these gentlemen do it with their penis. A penis that makes sound? Yes, indeed. The males rub their organ against the rough ridges of their abdomen to produce a powerful chirping that attracts the females. Sometimes this is called a “singing penis.” It’s quite charming. But let’s not rush to any conclusions about the origins of song in the male genital apparatus.

Attracting females in water poses a major problem: the wavelengths of sound in this element are long. For a potential partner to hear anything, mating calls need to reach a high volume to increase the range of the signal transmission. At the same time, the size of these insects’ body imposes a limit, and there’s also the danger of attracting predators. This is why male crickets and boatmen avail themselves of resonance structures that produce songs particular to each species, at a volume commensurate with their physical dimensions, which predators can’t pick up.

Despite their diminutive stature, these tiny insects can really belt it out. Their “singing penis” might be only 50 microns long, but they hold the record for the volume of sound emitted by any insect. It’s the loudest penis in the world! The chirping sound can reach 99 decibels. If you don’t know what to make of this figure, it’s as loud as listening to an orchestra from the front row. For reference, when an elephant sounds his trumpet, it’s just over 110 decibels loud—but an elephant is more than 2,500 times as large. Evidently, then, our little bug is the most effective noisemaker, in terms of acoustic energy relative to size, in all the wild kingdom.

More fascinating still, why such a powerful song has come to be is still a mystery, and the precise mechanism at work remains unclear. We must conduct more research in aquatic environments, especially on how the acoustic behavior and anatomy of these creatures have adapted to specific milieus. The intensity of their song qualifies as a secondary sex characteristic, which appears at the onset of sexual maturity—like antlers on deer, the songs of some birds, and changes in color among any number of animals. In this light, we can assume that the boatman’s song responds to strong pressure among males to find a mate: during courtship, competition prevails. The most winning sound will lure one or more partners. We need to do further work to find out how the females evaluate the relative attractiveness of singing penises. Does size—volume, that is—matter?

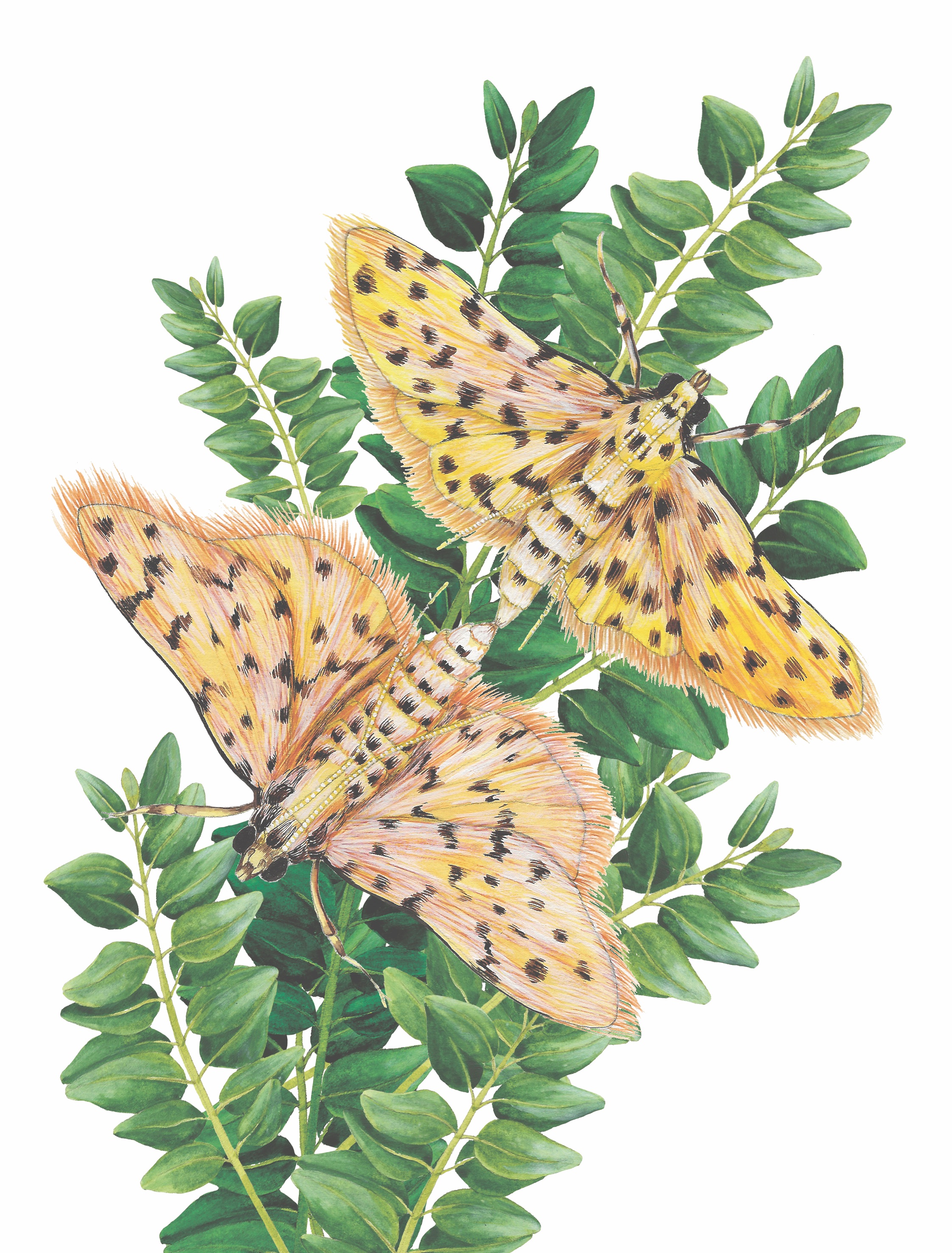

THE GRASS MOTH (Syntonarcha iriastis)

The water boatman is not the only animal out there with a penis that comes equipped with a sound system. Take the grass moth, a small insect of Indo-Australian origin. Males perch on trees and bushes, spread their wings, and expose their genitals. Evidently, this exhibitionistic display—their reproductive organs comprise files, scrapers, and resonance zones (among other things)—engages the mechanism that brings forth ultrasonic frequencies. Using a device originally designed for bats, researchers have detected the sounds at a distance of twenty meters. Needless to say, one assumes they’re calling on the ladies to mate.

But it is possible that these songs serve a different function altogether. Some of them strongly resemble the bursts of echolocation that insect-eating bats use to locate prey. Researchers have no doubt that imitating the sounds made by bats is a trick. The exact purpose of doing so is more enigmatic. Does it happen so that the female, sensing a predator’s approach, will freeze and stay put—making her available for suitors? It’s not out of the question.

Another hypothesis holds that the sounds emitted by this moth serve to scramble the sonar of the bats, making it harder for them to locate their prey. Once upon a time, I wouldn’t have been inclined to believe that noise made by genitals could be used to send predators down the wrong path. But nothing that goes on in the animal world surprises me now—especially since there’s no evidence that the females of the species are drawn to these ultrasonic transmissions at all.

Finally, scientists have proposed a third hypothesis, which was developed by studying the yellow peach moth (Conogethes punctiferalis). This time, competition between males is the issue. It would seem that they can shoo off rivals with a series of short impulses and woo females with sustained notes. Indeed, staccato emissions resemble the sounds bats make, while long ones prompt interested ladies to lift their wings as a sign of welcome. Dulce et utile, as classical wisdom would have it.

THE FOSSA (Cryptoprocta ferox)

A 25 lb. predator related to the mongoose, the fossa is the largest carnivore in Madagascar. Primatologists know the creature as a major predator of lemurs. Like lemurs, fossas are threatened by the dramatic decline in biodiversity on the island they inhabit. But that’s not why I mention these magnificent animals here; what I’m interested in is their extraordinary sexual adaptation. The fossa is one of the rare mammals among whom females, while still immature, undergo a passing phase of masculinization. What’s this, you ask? For a certain period, they make others think they’re male. This trick is quite handy for communicating false information and thereby ensuring the females’ own safety. So how do they do it, and who—or what—are they protecting themselves from?

For the phase in question, the clitoris grows in size; then the extended organ develops spikes that make it look as if it belongs to an adult male of the species. It seems that the girls deck themselves out with this feature to avoid aggression on the part of guys looking to mate; the thorny clitoris acts as a deterrent. In brief, transient masculinization enables young female fossas to avoid sexual harassment and improve their prospects for survival. Unwelcome attention from males, after all, can lead to injury or even death. The fact that mature females aren’t always around and the annual estrus cycle doesn’t last for long makes males try to mate quickly and frequently—hence their aggressive behavior. Juvenile females are especially vulnerable because they’re small and have just left home, as it were. The disguise effected by clitoral transformation enables them to escape detection by males. Plus, genitals like this would pose a barrier to coition. Quite the radical solution!

At the same time, masculinization serves to protect juvenile fossas from others of the same sex. Danger is everywhere. While males seem somewhat territorial—data from radio tracking are limited—mature females have areas they consider entirely their own. At the age when they are just starting to leave the home, young lady fossas haven’t yet found their place in the world and risk unfortunate encounters with older females. An enlarged clitoris helps avoid confrontation.

Whatever the reason for morphological and behavioral differences in animal sexuality, they surely exist. The most widely credited theory is that distinct reproductive organs developed to discourage mating between different species; that said, such a precaution seems unnecessary, since encounters between different kinds of animal, when they take place at all, produce only sterile offspring.

At any rate, diversity clearly thrives at all levels: social interaction between males and females (competition, monogamy, multiple partners), modes of seduction (building bowers, offering gifts, a new coat or plumage, tricks), parade techniques (dancing, singing), mating itself (on the ground, in flight, in various positions), and setting and circumstances (out in the open, in the forest, with predators nearby or absent). There’s no reason, then, why morphology shouldn’t display comparable variation. Nothing has been set in stone. Human beings haven’t come up with anything new. Humility is in order here. “Sexodiversity” existed long before we ever came along. As always in the animal world—no matter which aspect—a world of discovery awaits.

This essay is excerpted from Sexus Animalis: There is Nothing Unnatural in Nature. Copyright © 2022 by Emmanuelle Pouydebat, translated by Erik Butler. Used with permission of the publisher, MIT Press.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com