China promised a “simple, safe, and splendid” Beijing Olympics. While the elaborate, anti-COVID measures at the 2022 Winter Games were far from simple, organizers managed to put on a show, even amid the constrained circumstances of a global health crisis. There’s also no doubt that the event was safe.

COVID-19 has been surging around the world, fueled by the more contagious Omicron variant. On Dec. 27, just over a month before the Winter Games began, global daily COVID-19 cases hit a record 1.44 million.

Despite these daunting circumstances, Olympics organizers had recorded only 437 infections at the Games by the time the flame was extinguished at Beijing National Stadium on Feb. 20. Though more than 180 athletes and team officials tested positive after arriving in China, there were no major disruptions to events caused by outbreaks.

For China, containing the coronavirus on an epic scale is not new. The country unhesitatingly puts entire cities on weeks-long lockdown, and conducts massive testing, tracing, and vaccination operations, under its “dynamic zero COVID” policy. It can’t afford to do otherwise: some estimates show that China would have suffered as many as 200 million infections and 3 million deaths by now, if it had attempted to “live with the virus” as most countries do. Instead, less than 131,000 cases and 4,924 deaths have been recorded in China since the start of the pandemic.

In this context, it was vital that the staging of the Olympics—with thousands of participants arriving from 91 countries—not lead to a wider community outbreak. To protect its citizens, China ran the Beijing Olympics on a strict “closed loop” system: participants and venues were confined to epidemiological bubbles, strictly segregated from the city at large.

Read more: What to Know About the 2022 Winter Olympics Closing Ceremony

“They basically thought of the bubble as a similar kind of setting [to the rest of the country],” says Karen Grépin, an associate professor at the School of Public Health at the University of Hong Kong.

It worked. Participants testing positive recovered in the loop, with many continuing to compete. Speaking at a press conference on Feb. 18, International Olympic Committee (IOC) president Thomas Bach said the infection rate at the event stayed at 0.01%. He called the closed loop “one of the safest” places on Earth.

Although some athletes pushed back against the rigors of Beijing’s approach, the Winter Games demonstrated China’s capability to keep Omicron at bay—something no other country has done effectively. They reveal just how much cooperation, organization, and expenditure are required to stage a large scale international event safely. Grépin calls the Olympics “an enormous planning effort,” based on “two years of really good data and evidence in terms of how COVID-19 spreads.”

How the Beijing Olympics kept Omicron at bay

Beijing is the second city to stage the Games during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it tried to learn as much as it could from Tokyo’s infection control playbook for the Summer Olympics last year. A surge in cases occurred after the Tokyo Games ended in August. Both the IOC and Japan denied that the Games caused the spike, but this was an area that Beijing especially wanted to address.

Around 19,000 local volunteers agreed to spend up to two months away from their families to help out at the Games. It meant that they would not spend Lunar New Year—China’s most important holiday—with their loved ones. To prevent any chance of a post-Olympics outbreak, they also consented to undergo a 21-day quarantine after the Olympics before being allowed home. One volunteer said “professional psychological training” was given to help them adjust “our mental state.”

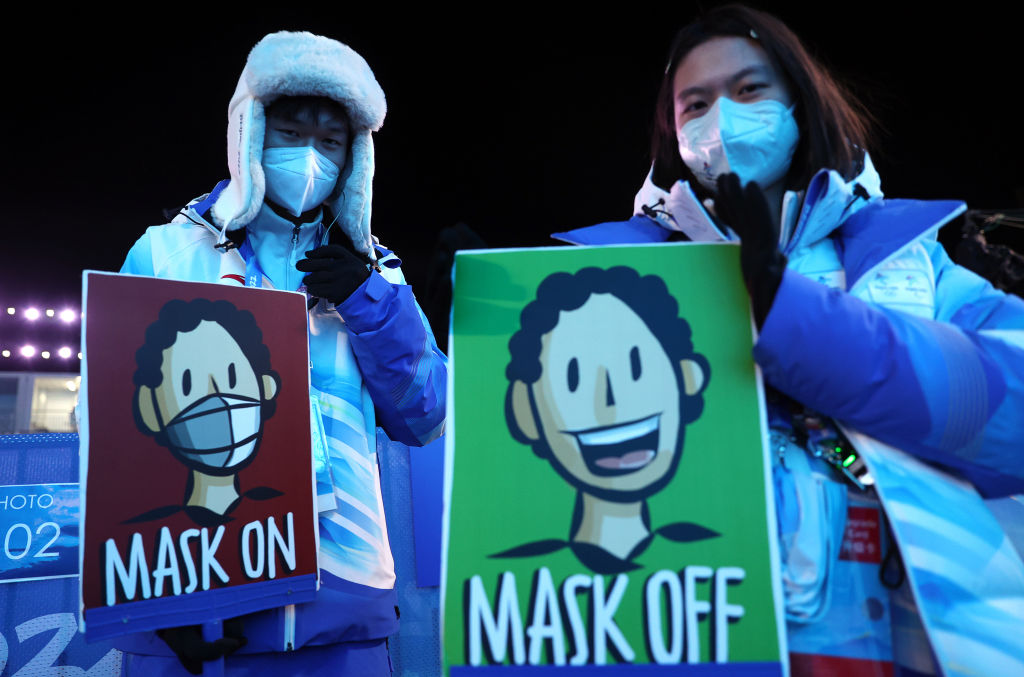

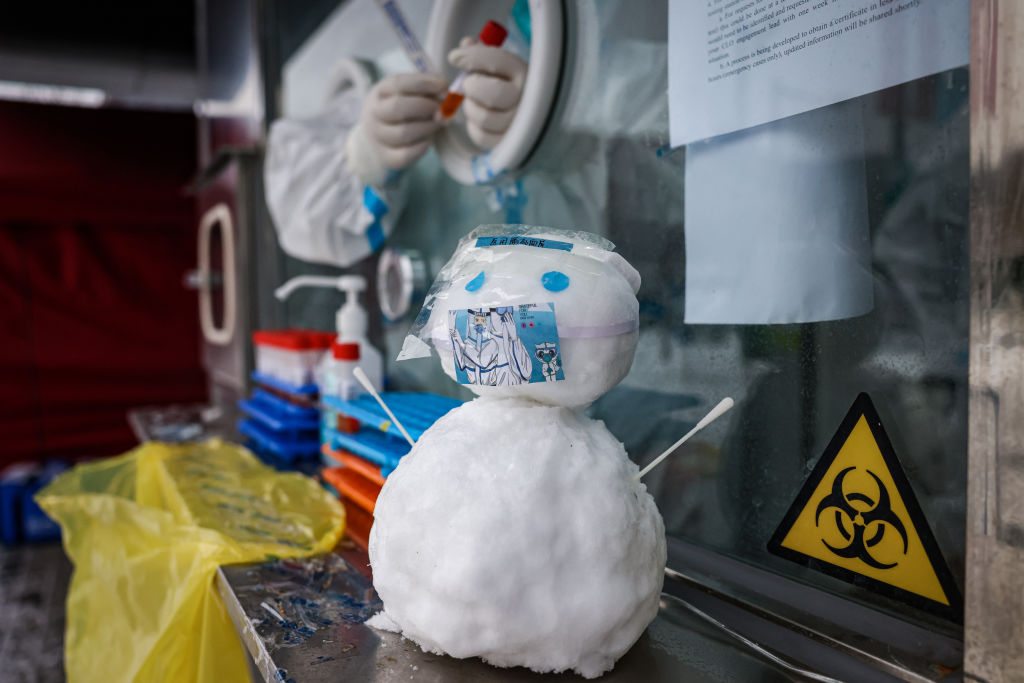

From the time Beijing’s closed loop system took effect on Jan. 23, organizers administered more than 1.8 million COVID-19 tests—at least one per day for everyone involved. Masks and contract-tracing apps were naturally mandatory. On-site spectators were kept at a minimum. As a televised and online spectacle, the 2022 Olympics were the most watched Winter Games ever. But over its 19 days, only 150,000 people saw in person the sporting events in Beijing and neighboring Zhangjiakou.

Athletes, upon arriving in China, had to mostly stay in their rooms when not training or competing. Not all were up to the challenge. U.S. snowboarder Jamie Anderson—who won gold in 2014 and 2018 but failed to medal in Beijing—told USA Today that most of the U.S. snowboard team was “tired of the pressure,” and “a little bit tapped out.” Some athletes testing positive complained about the lack of training equipment and the quality of the meals in quarantine, although gripes do seem to have been eventually addressed. Belgian competitor Kim Meylemans briefly made headlines with a tearful Instagram video after she tested positive for COVID-19 on arrival in Beijing and was sent to an isolation facility, even though subsequent tests were negative. She was brought back to the Olympic Village a few hours later.

Read more: What Happens if an Athlete Gets COVID-19 at 2022 Olympics?

“Such kind of isolation is a challenge for everybody, but for the athletes, it’s the heaviest to bear,” Bach told media. But he said that while the isolation facilities in Beijing “did not work perfectly,” Olympic officials made efforts to fix issues that came up.

Many athletes actually welcomed the infection control protocols. American freestyle skier Aaron Blunck said that China did a “stellar job” with the COVID-19 measures. Britt Cox, a four-time Olympian, told Australian state-funded broadcaster ABC that regular testing inside the bubble gave her “a lot of peace of mind” and allowed her to focus on competing.

Canadian figure skater Keegan Messing missed the team skating sporting event after testing positive for COVID-19 before his flight to Beijing, but recovered just in time to travel to the Olympics and skate in the men’s single’s category. While he “had not seen anything of Beijing, other than a bus, my room or the rink,” he lauded what he thought was a “great” atmosphere in the Games. As for the restrictions, Messing told TIME that athletes had already have been dealing with COVID measures for most of the season: “So how strict Beijing is, it’s just really another competition for us.”

Among athletes testing positive, only a few were unable to actually compete. Vincent Zhou had to withdraw from the men’s figure skating competition after testing positive, but that was after he helped the U.S. win silver in team figure skating. (No other team members tested positive.) Neither did a positive test end the dream of making the podium. Three-time U.S. bobsled medalist Elana Meyers Taylor recovered from infection in Beijing—and bagged silver for the inaugural women’s monobob event.

Learning from Beijing’s ‘closed loop’ system

Lessons on how to stage a virus-free international event can be learned from the Beijing Olympics, experts say, even in countries that don’t follow zero-COVID policies. “You might receive some resistance,” says Dr. Huang Yanzhong, senior fellow for global health at the Council of Foreign Relations, “but I still believe that is doable.”

Grépin agrees, saying that Beijing has set a new benchmark: “It’s sort of a gold standard that isn’t necessarily what other places that are not striving for zero COVID will need to put into place.”

Read more: Don’t Expect China to Ease Its Zero-COVID Policy Soon

It may be premature to call the closed-loop system a total success. The system will still be in place until the end of the Paralympics in March, and only when volunteers re-enter the community will its effectiveness be truly known. “When they dismantle the bubble, we’re going to have to test and see what will happen,” says Grépin.

But putting together tens of thousands of people in a closed loop, with many flying in from countries currently being ravaged by Omicron, and managing to keep a highly contagious disease at bay, is a feat that can’t be denied to China.

“This is a great achievement,” Bach told reporters. “It may send the message to the world that if everybody is respecting the rules in solidarity, and if everybody’s contributing, then you can even have such a great event like Olympic Winter Games under the terms of such a pandemic.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com