Joseph Nappi is a 20-year-old Starbucks barista and Cleveland State University political science major. He’s also learning how to be a union organizer.

“My family is a union family,” Nappi says. His late grandfather was the president of the United Steelworkers of America union in Ashtabula, Ohio. “They gave my grandfather a fantastic pension that allowed him to send my dad and his brothers to school,” Nappi says. “We still get benefits from his pension now to help afford my grandmother’s memory care. If it wasn’t for United Steelworkers, I don’t know where we would be with supporting my grandma.”

Nappi has been with Starbucks since June of 2021 but moved to his current location in downtown Cleveland in September of last year. Last month, Nappi and a coworker started talking about unionizing. “One of the main motivating factors for the partners at this store to try and unionize was our partners in Buffalo,” he says. “What they’ve done out there, I think it really lit a fire under us to start the process of filing for an election and trying to become a unionized Starbucks.” Seventeen of the store’s 20 partners (Starbucks’ term for employees) signed union cards. In the age of COVID, the signatures were digital.

In December, workers at three company-owned Starbucks stores in Buffalo, N.Y., held votes and hearings in front of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and formally organized with Workers United, a Service Employees International Union affiliate. Two of the three locations voted for the union and are now unionized. Since then, more than 60 (the numbers keep changing daily) company-owned stores across the country, from Massachusetts to California, have filed for union elections, including three in New York City, according to the NLRB. Two of the companies’ three U.S.-based flagship stores/roasteries have filed; one is in Seattle, the other in New York City. Starbucks opposes the unionizing efforts and has set up a website outlining its stance. The company has been accused of union-busting efforts, including firing employees involved in organizing their stores. Employee-led marches and rallies were planned across the country for Tuesday after the company fired seven employees in Memphis, Tenn. Union organizers allege that the firing was in retaliation to their trying to organize their store.

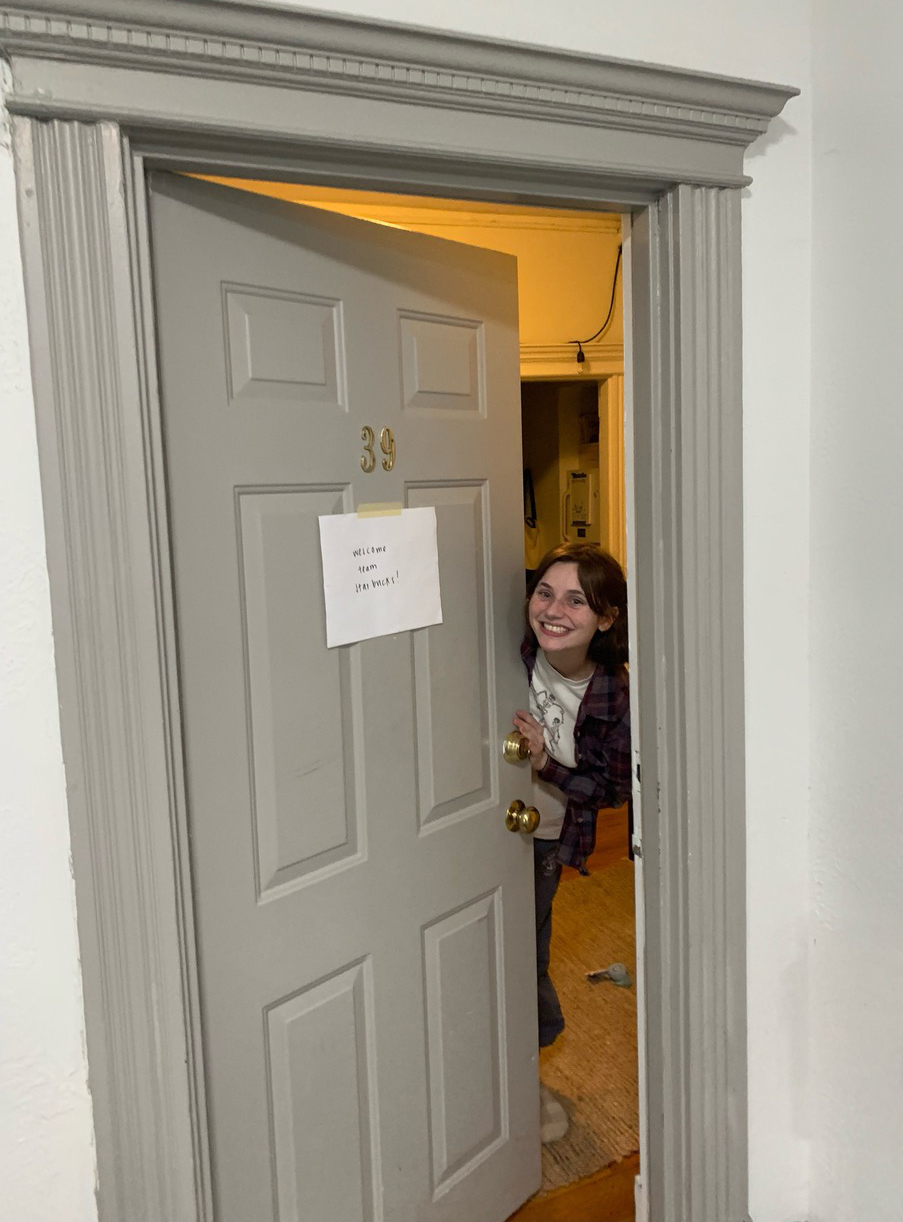

This union organizing has a very different image than the picket lines and factory floors of previous generations. Many of the Starbucks organizers are in their 20s—the average age of a barista is 24—and are tweeting their calls to unionize, running Zoom onboarding meetings for other would-be organizers, and holding organizing get togethers in their living rooms or at local bars.

Nappi says that most people think of traditional union jobs as steel workers, teachers, or construction trades. “But we live in this new time, during what’s been called the Great Resignation,” he says. “It’s really turned everything upside down. Workers are finally realizing that they have this right to organize and that they can demand more from their employers. That’s what we’re doing at Starbucks. We don’t want to be part of the Great Resignation because we like our jobs and we want to keep working at Starbucks. But we want to make Starbucks a better place to work for all of us.”

In Buffalo, N.Y., Cortlin Harrison echoes that sentiment. When the 25-year-old was looking for a job last fall, he started blanketing local Buffalo businesses with his resume, hoping to get a response. For most of the jobs, he simply uploaded his resume to a career website and hit send. But he took a lot more time and care with his Starbucks application, he says. He had heard about the many benefits the company provides, and about his neighborhood store possibly becoming the first one to unionize.

Harrison says that as a teenager, he worked for numerous fast-food companies: McDonalds, Burger King, and Subway. “None of them really cared about the workers, so I felt no loyalty to them,” he says. And none of them offered the benefits Starbucks does; Harrison was especially interested in college tuition being covered. “But even with all the benefits, at the end of the day, it comes down to pay,” he says. “It’s great that they offer health insurance and they offer to pay for my school, but if I can’t afford my rent, what does any of that matter?”

Harrison signed his union card his first day on the job.

“It’s exciting,” he says. “I’m working at the first American store to unionize. It’s a big deal. I think what we do here sets the tone for what other stores can accomplish. I think that all the eyes are on us right now.”

Some of the older workers, who have worked for the company longer, were behind the initial push for the union. Michelle Eisen, 38, works at the same Buffalo store as Harrison and has been working at Starbucks for a little more than 11 years, both part time and full time. In her 20s, she took the job because her other job as a production stage manager didn’t have benefits. “I needed a job that would provide those benefits for me. And I’d heard really great things about Starbucks as a company and how flexible they were and the benefits they provided,” she says. “They really were that company when I started with them.”

But Eisen says she has noticed a “pretty big decline” the last four years with the cost of benefits going up while the coverage goes down, among other changes. “It has been a pretty clear shift from partners to profits,” she says. “It’s very much, ‘Get a body in there and get them to produce as much as they can produce in whatever time period they’re able to give you.’ And then whatever happens to them doesn’t really matter. It’s been very disappointing to see this change.”

The problems only magnified under the pandemic, she says. “Starbucks really capitalized on the fact that, because they remained open throughout all of this as a company, it represented to their customers and the public the last ditch of normalcy: no matter what was going on in the world with COVID, you could still get in your car and drive to your local Starbucks and get your caramel macchiato,” she says. “It began this push within the company to not only produce at the rate we were producing pre-COVID, but to exceed those expectations, at any cost, in my opinion.”

The changes felt too big and unsafe for Eisen, so she planned to leave in fall 2021, after her next stock vesting period. “But then, suddenly, this opportunity to organize and form a union and have some sort of voice where we felt like we didn’t have one presented itself,” she says, “And that’s what brought me to this cause.”

The action in Buffalo struck a chord with young baristas across the country, like Nappi in Ohio. “When I first started thinking about organizing, it had been after seeing what was going on in Buffalo, and the swift corporate reaction,” says Kylah Clay, 24, who works at a store in Boston, Mass. “It was a very slow process of very discreetly speaking with people to get a gauge on how they feel about it and then eventually forming a small committee and a lot of logistics from there.”

Before the union drive, Clay and Tyler Daguerre, 26, had never met, just lived parallel lives: working at different Starbucks in the Boston area while going to law school. But when both of their stores decided to unionize, the first two in Massachusetts, they quickly became the de facto leaders and began helping people at other stores do the same. Now the two talk like friends who have known each other for years, laughing simultaneously and finishing each other’s sentences.

For Daguerre, it has been nonstop activity since his Brookline store filed paperwork back in December. “It has actually been crazy. We were just doing another onboarding meeting with someone yesterday who was a partner for seven years. We have another partner who’s been with Starbucks more than 10 years who wanted to do it. But then I also got a message today from someone who has only been working at Starbucks for a week and is asking how they can get involved and how they can get their store on board,” says Daguerre.

The majority of organizing is virtual and all of the onboarding meetings are conducted via Zoom, says Clay. While this approach poses some challenges, it allows organizers to communicate and collaborate with baristas across the nation, she says. “We’re helping the organizers by essentially onboarding them and giving them all the information we have. They don’t have to reinvent the wheel. We are helping them through the process and kind of streamlining things so that way, once they feel ready, they don’t have to go through all the hoops and logistics.”

When a worker emails Clay’s team wanting to learn more, they set up an initial meeting via Zoom and run through a broad overview of unionizing. Then she follows up to focus on the step-by-step details. “Once they’re ready, our team in Massachusetts prepares starter kits with union signing cards, shirts, and buttons so they can get the process kicked off,” says Clay. “I help them gather everything for their petitions and provide this information to the union attorneys for filing.”

Clay has already helped onboard 10 stores. “At first, we’d get connected to baristas interested in unionizing their store through coworkers,” she says. “Now, we’ve been doing outreach and visiting stores to spread the word and help them get connected to our team.”

Grant Graves, 22, has been carefully watching unionizing efforts like Clay’s in Boston and others elsewhere via social media at his barista job at a Starbucks in Gainesville, Fl. The University of Florida senior has been working at Starbucks on and off since 2016.

“Before the union success in Buffalo, most partners did not think unionization was possible within Starbucks,” he says. “Now, I think many more are hopeful that unionization could become a reality.”

But Graves isn’t so sure his store–or others in Florida, even the one in Tallahassee that organized last month–will be successful. “To be perfectly honest, here in Florida, I think it is more likely that my fellow partners and I will be fired for trying before actually achieving union representation, but I think it is worth trying anyways,” he says.

When customers have asked about union prospects, he has had to tell them he is not allowed to discuss it while on the clock. But he has definitely felt the support in subtle and not so subtle ways.

“One [customer] changed the name on their mobile order to ‘Union Strong,’” he says.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com