A version of this article was published in TIME’s newsletter Into the Metaverse. Subscribe for a weekly guide to the future of the Internet. You can find past issues of the newsletter here.

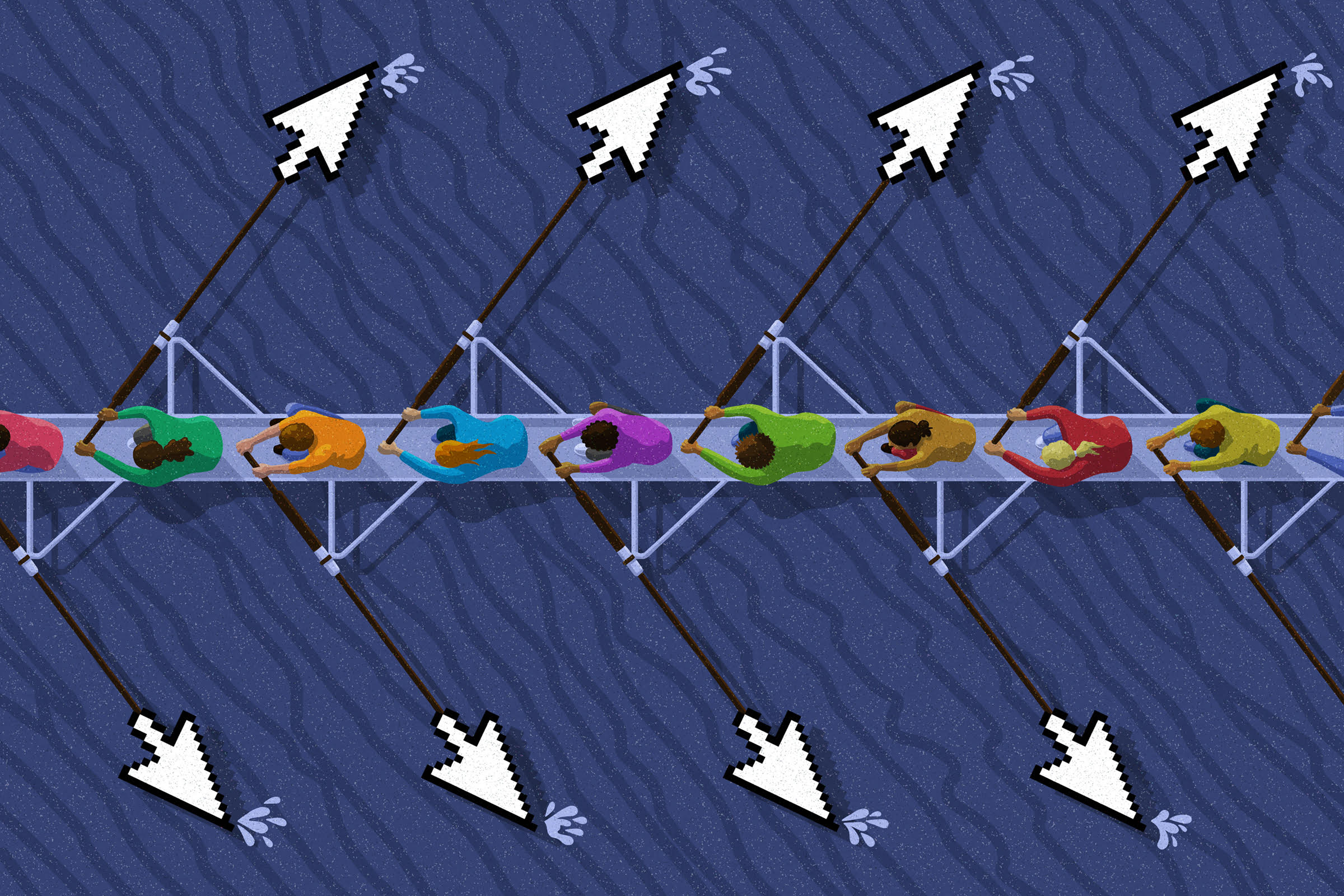

In January, many people on Crypto Twitter proclaimed that if 2021 was the year of NFTs, then 2022 would be the year of DAOs. DAOs, or decentralized autonomous organizations, are a new-ish type of organizational structure that have proliferated rapidly in the last couple years as money has poured into the crypto space. They’re an extension of the crypto world’s promise of decentralization: Instead of being owned by one person or controlled by a board, they’re collectively owned by participating members, with decisions being voted upon and rules enforced through smart contracts.

Aaron Wright, a lawyer and co-founder of Flamingo DAO, which invests in NFTs and creative projects, likens DAOs to “a subreddit with a bank account.” “The energy of the Internet is swarmlike, but there’s no real productive way to channel that,” he says. “I believe DAOs are that answer.”

Enthusiasts believe DAOs could eventually replace many traditional companies as sort of new-age co-ops. (Imagine a version of Uber where the drivers collectively own the company, for instance.) At the moment, though, most DAOs are focused on crypto and Web 3 activities. There are DAOs that collect NFTs (PleasrDAO), facilitate cryptocurrency exchanges (Uniswap), build blockchain products and tools (PartyDAO), and incubate and fund NFT artists (herstoryDAO, the Mint Fund).

But skeptics point out that many DAOs aren’t particularly decentralized and are limited in their ability to navigate the unpredictable complexities of human organizations. “Calling a DAO a revolutionary structure is smoke and mirrors: It’s just voting shares,” the video essayist Dan Olson argued in his viral YouTube video, “Line Goes Up – The Problem With NFTs.” Earlier month, the New York Times published an article pointing to some of the struggles of DAOs, including massive hacks, low voter turnout, and internal strife.

While some DAOs have flamed out spectacularly, there are others that are humming along quietly, offering an alternative model for what a workplace might look like. One of those is dOrg, one of the very first DAOs to be legally recognized as an LLC in the United States. dOrg, which was officially formed in 2019, is a software development company that helps build infrastructure for Web 3 and crypto projects. I interviewed four members of the DAO to find out what makes dOrg different from traditional LLCs, and how these differences help or hinder their work.

There is no management team, and everyone owns the company

To start from the top, dOrg has no general management positions (CEO, CFO, etc). While the software engineer Ori Shimony co-created the company, he doesn’t have an official leadership title, instead describing himself as “helping with research and development.”

Instead, roles are fluid, with people sliding into different roles depending on each project. Everyone who officially works at the company is a legal owner of its Vermont LLC, with each owner owning one share. Company decisions are voted on using tokens, which accrue as you complete projects for the company. (Accordingly, Shimony has the largest share of the company’s tokens, at about 9%, but that share has been decreasing steadily since the company’s inception and will continue to do so.)

Colin Spence, a full-time product designer at dOrg, says learning about this ownership model was a “huge wake-up call.” “At pretty much every company I’ve ever worked at, I’ve been told by my bosses, ‘I really want you to own this project.’ But it’s not actually true. Now, everything I build, I own. It totally changes how you want to manage your time.”

The company isn’t completely non-hierarchical, however. Specific aspects of projects are led by specialists (i.e. in tech, project management, etc). But, a leader on one project could find themselves reporting to their subordinates on the next one. “There’s a difference between leadership and authority,” Shimony says. “There’s no one authority to wave a wand and make a decision. But it’s really helpful to have someone, or ideally multiple people, provide advice, guidance and direction.”

Developers choose their own projects and control their own budgets

Work hours and locations are flexible and self-driven. The employees I talked to lived in three different countries, and none of them said they worked over 45 hours a week. They also talked about having a large degree of autonomy in finding projects to work on, cultivating relationships with clients, and then forming teams to execute those plans. dOrg project manager Magenta Ceiba, for example, is passionate about regenerative farming and supporting economies at the local level. When she came across AcreDAOS, an investment club focused on those issues that needed development help, she wrote a proposal that was quickly accepted by the token holders at dOrg. “The values alignment was particularly high on this project,” she says. “Many of the builders in dOrg are from Venezuela, so they have a deep understanding of what happens when economies are broken.

Nestor Amesty, a tech lead who is himself from Venezuela, says that the developers handle budget allocation themselves. “We co-audit ourselves,” he says. “If someone is abusing the budget—which has definitely happened in the past—his or her peers will have the responsibility to raise their voices if they see something they do not agree with. We have a clear structure on how to proceed if conflict arises.”

Conflicts are mediated and then voted on.

Without having a central authority to rule on spats, employees first abide by the company’s guidelines for “decentralized dispute resolution.” Sometimes a People Ops specialist (essentially an HR worker) serves as a mediator. “That’s been working pretty well recently,” Magenta says. “We have a culture of being direct and forthcoming with each other.”

It’s not uncommon for Shimony himself to be overruled. He says that when he wanted dOrg to issue a public token—so that investors could buy a quasi-stake in the company—the idea “died in committee” after being discussed over several calls. “I argued with them; the decision went the other way and I’m glad it did,” Shimony says. “dOrg is what it has become.”

If decisions aren’t resolved in discussions, then the DAO members vote on the blockchain. Spence says the company used to vote on nearly every decision, which led to an “information overload and a constant barrage of needing to feel like you needed to keep on everything that was being proposed.” While this process was perhaps the most inherently democratic system, it hampered forward progress, so the company began to delegate decisions to smaller and more specialized groups.

The company outsources health benefits

For now, dOrg is partnering with Opolis—which sells health care for digital workers and freelancers—to provide health insurance for its U.S.-based members. Ceiba, who lives in California and is on state insurance, says she is interested in advocating for the company to explore its own insurance options now that “we’re starting to have a healthy enough treasury to revisit that.”

Salaries are transparent

When it comes to pay rates and finances, dOrg aims for “radical transparency.” All salaries and budgeting are publicly maintained on the blockchain; payout logs are visible to each member.

And employees are paid according to their skillset no matter where they live in the world. Amesty, who moved to Madrid from Venezuela after joining the company, says that when he previously tried to work for Latin American agencies, “they usually strong-armed developers to work for lower wages, because they know that Venezuela is in a very hard situation. After I started to work with dOrg, feeling my nationality didn’t matter—it was my work and what I was delivering.”

In another interesting wrinkle, employees who work on specific projects can elect to either get paid in cash, or in tokens that represent an ownership stake in those projects. If they choose that latter option, they are sacrificing immediate spending money in favor of the idea that the valuation of the tokens will increase as their projects mature.

For instance, Amesty helped build the development platform Polywrap and says he chose to get paid almost exclusively in tokens, which will vest after 4 years. “I truly believe that [Polywrap] has a lot of potential to grow in the coming years, and want to be a part of that,” he says. “It also motivates me to want to make things as good as possible, since I have skin in the game.”

Skill-building is still a work-in-progress.

A hierarchically flat company could theoretically lead to worker stagnation, in which employees feel unmotivated to build skills or advance. To combat this, the dOrg’s handbook places an emphasis on “upskilling” and creating a collaborative structure in which employees with different skills learn from one another. “When people form teams, the senior developers will encourage more junior developers to take on a bigger chunk or a new skillset,” Ceiba says. Workers with more expertise, or additional skills, then get paid more.

Spence hopes the self-improvement process will become more formal, with a guide to skill sets developers need to master in order to achieve higher pay grades and status within dOrg. He envisions a system where developers can sign up to build various skills on each project, which are then peer-reviewed by collaborators. “So there’s this constant mechanism of evaluating a builder’s performance and ensuring they’re actually building the skills they need,” he says. Spence says he has proposed this idea in the past and hopes to help it get implemented over the next year.

Until then, the dOrg will keep taking on projects, voting on new proposals and trying to streamline technical processes. “A lot of things just started as experiments, and there are things that need ironing out,” Amesty says. “But it works. And I hope I can be around for a long time.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Home Losses From L.A. Fires Hasten ‘An Uninsurable Future’

- The Women Refusing to Participate in Trump’s Economy

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Dress Warmly for Cold Weather

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: No One Won The War in Gaza

Contact us at letters@time.com