Abt, a Senior Fellow at the Council on Criminal Justice, is Chair of the Council’s Violent Crime Working Group and the author of Bleeding Out: The Devastating Consequences of Urban Violence - and a Bold New Plan for Peace in the Streets. Eddie Bocanegra, a member of the Violent Crime Working Group, is Senior Director of READI Chicago. Tingirides is a Deputy Chief of the Los Angeles Police Department, where she serves as Commanding Officer in charge of the Community Safety Partnership Bureau.

Just before Thanksgiving in Philadelphia, dozens of residents gathered on a basketball court in the city’s Lawncrest section to mourn the loss of Jessica Covington. Thirty-two years old and seven months pregnant, Covington had been shot and killed a few days earlier while unloading gifts from her baby shower. Colwin Williams, a street outreach worker who has been to dozens of gatherings like this one, spoke to the group. “We can’t tolerate this,” he said. Later, he expressed what so many were feeling, “The pain is everywhere.”

Last year in Philadelphia, the City of Brotherly Love, 562 citizens were murdered—an all-time high and a 12 percent increase over 2020. Almost 90 percent of these homicides involved firearms, and the spike followed an even bigger surge in 2020, when killings were up by 40 percent. The numbers are sobering, but gun violence has been climbing in the city since 2013.

Philadelphia is not alone. At least ten other major cities lost historic numbers of residents to murder last year. Nationally, police data suggests homicides rose seven percent in 2021. And while many Americans know that 2020 was a particularly bloody year—with homicides surging 29 percent, with 77 percent of them involving firearms—few realize that gun violence has been rising across this country since 2014. Fatal shootings have increased by roughly 80 percent in the largest U.S. cities since then.

In Philadelphia and elsewhere, gun violence isn’t spread evenly. Instead, it clusters around relatively few city blocks, and among small networks of high-risk people. In Philadelphia, there are at least 57 blocks in which ten or more people have been shot in the past five years. Recent research shows that during the pandemic, marginalized communities bore the brunt of the increase in such violence. A forthcoming study shows the same is true since 2014. Most of these neighborhoods have suffered high rates of violence and poverty for generations. This suffering can ultimately be traced back to policies of racial segregation and disinvestment that began in the early twentieth century. In Philadelphia, 53 of the 57 most dangerous blocks were subject to racial redlining policies in the 1930s that denied residents of predominantly minority neighborhoods access to mortgages.

Why is gun violence rising right now?

First, violence in the U.S. has been persistent for years so we’re coming from a very high baseline. Second, COVID-19 has presented major challenges, but it’s important to note that violence, especially gun violence, actually started increasing nationally in 2014. In addition, violence has not increased in most other high-income countries during the pandemic. So it’s not only the pandemic, but our politics, that presents a massive challenge.

American politics is hyperpolarized, and the criminal justice arena is no exception. The public is consistently presented with a false choice between absolutes: it’s all about tough policing and prosecution, or it’s the police and prosecutors who are the problem. It’s #BlackLivesMatter versus #BlueLivesMatter. A few leaders push back on this frame, but this either/or construct is the dominant criminal justice conversation in the country. This us versus them dynamic is profoundly destructive to sound anti-violence efforts because everything we know about violence reduction tells us that we need law enforcement, but we need community and other partners as well. And most importantly, we know that a single approach won’t work—we need everybody to work together. Unfortunately, the current conversation makes such partnerships nearly impossible.

The fact is, we can have safety and justice at the same time. We can reduce violence and promote reform simultaneously. We can be tough when the circumstances call for it and be empathetic and supportive to achieve our goals as well. We have to reject either/or choices and insist on both/and options. We have to remember that it’s about solving a deadly serious problem, not winning an abstract argument. It’s about bringing people back together, not pulling them apart.

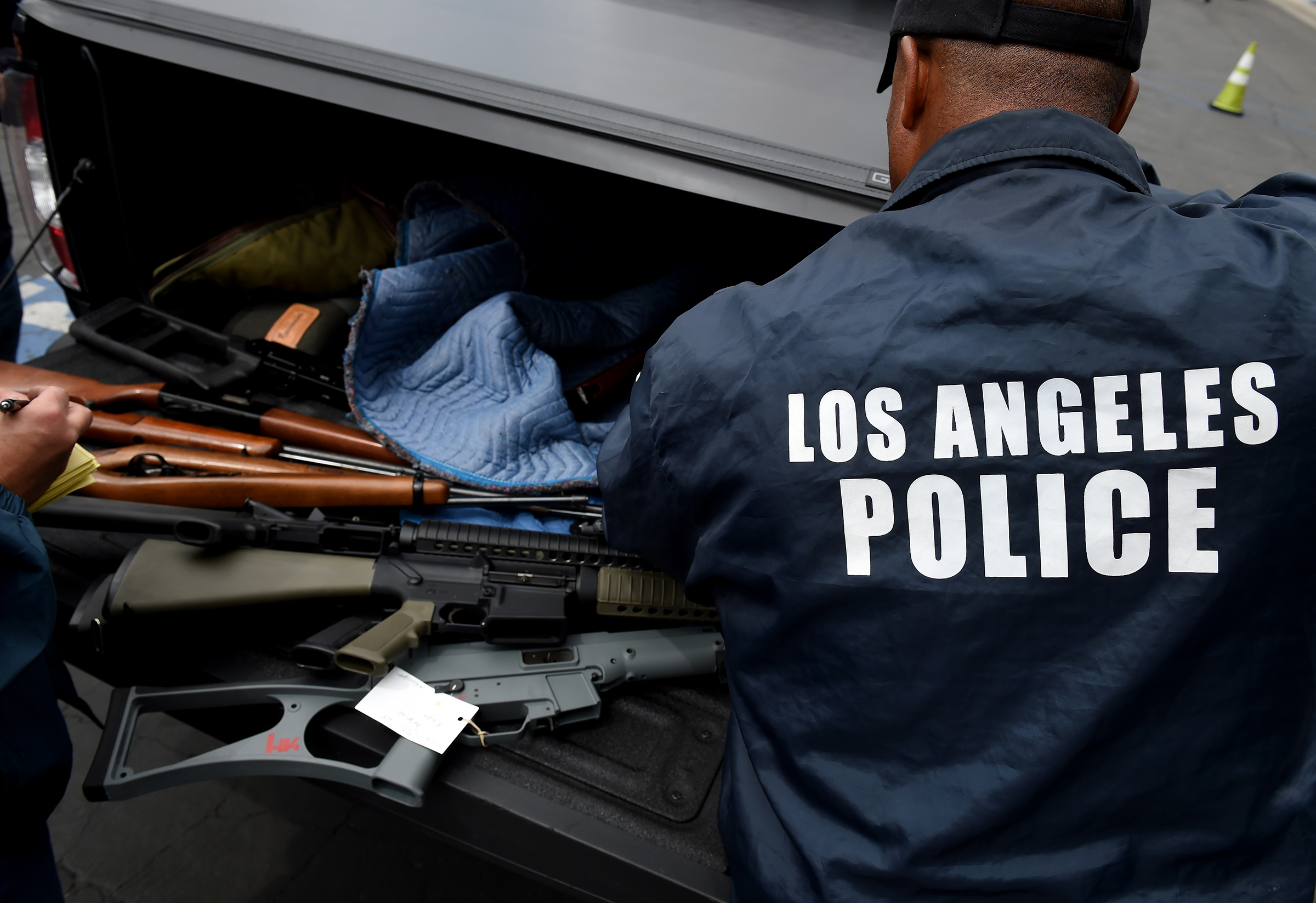

Our politics is also the main impediment to another uniquely American aspect of the challenge: millions of guns, many of them falling into the wrong hands. Although the majority of Americans support reasonable restrictions on the right to bear arms, Congress and many state legislatures have been unable to pass such legislation. This isn’t about bans; it’s about adopting some of the same commonsense requirements we all meet to drive a vehicle—minimal training, a permit indicating we’re in good physical and mental health, and so on. If anything, many states are moving in the wrong direction: last year, six more states (now 21 in total) passed “permitless carry” laws, undoing requirements that citizens secure a permit before carrying a concealed firearm in public.

Given all this, some might suggest that nothing can be done, but that is not the case. In fact, rigorous research as well as lived experience tells us just the opposite. One of us is a Deputy Police Chief in Los Angeles. One of us runs a major anti-violence initiative, READI, in Chicago and spent much of his youth in a street gang. And one of us is a former prosecutor and justice official who now researches gun violence. All of us have witnessed what is possible when people put politics aside and concentrate on saving lives by stopping violence, and our experiences are backed up by data.

In Los Angeles, Community Safety Partnership (CSP) officers work in collaboration with community stakeholders in some of the city’s toughest neighborhoods. They work tirelessly to connect residents with public and private resources and form alliances with public health professionals, prosecutors, community advocates, gang interventionists and educators. CSP’s immediate goal is improved public safety; its long-term vision is thriving and healthy communities. It’s working: a recent report shows that CSP reduced crime while improving relationships with residents.

In Chicago, the Rapid Employment And Development Initiative (READI) works with those at the highest risk for gun violence to help them stay safe, free from incarceration and able to support themselves and their families. READI uses cognitive-behavioral techniques such as practical exercises and activities to help participants recognize problematic thinking and behaviors, and then supports them with subsidized employment and other services. Despite participants’ criminal backgrounds and deep histories of trauma, an early analysis indicates that READI is substantially reducing arrests for shootings and homicides among program participants.

Across the country, there are dozens of strategies like these with documented success in reducing gun violence. Oakland Ceasefire is a celebrated police/community partnership that confronted high-risk individuals and groups with a double message of empathy and accountability and cut firearm homicides in that city by 31 percent. The well-known Advance Peace effort in Richmond used conflict mediation, intensive mentorship, case management and life skills training to reach people at the highest risk for violence, reducing firearm crimes by 43 percent. The famous Cure Violence approach uses community-based outreach workers to mediate potentially violent conflicts, reducing gun injuries in two neighborhoods in New York City by 50 and 37 percent, among other places. Even Philadelphia has received national recognition for an innovative approach by its Horticultural Society that reduced gun violence by 29 percent by “cleaning and greening” vacant lots and buildings.

Unfortunately, we’ve learned over time that no single strategy, whether led by police or community members, can stem violence all by itself. While certain anti-violence programs can succeed in isolation, violence citywide typically remains stubbornly high because no intervention is strong enough to resolve it on its own. For large, sustained declines in violence, cities need a collaborative effort that leverages multiple strategies at once. And because of the toxicity of our politics, many cities struggle to mobilize—and sustain—a multi-dimensional response that depends heavily on collaboration.

How we move forward

Articulating and then translating a city’s anti-violence vision into action requires clear and consistent leadership to put all the pieces together in a coherent way. Leaders must agree on a framework that identifies what to prioritize and shows how each key player will work together. Last summer, the independent Council on Criminal Justice created a Violent Crime Working Group to help cities do just that. We are three of the group’s 16 members, and we are releasing our final report, which outlines ten essential actions every city can take to reduce gun violence right now. Here, we will preview just a few.

First, city leaders must recognize the devastating human and economic costs of gun violence. Perhaps this sounds obvious. But when the numbers pile up, individual lives sometimes become obscured. Every lost soul is priceless, and a single gun homicide costs as much as $17 million in economic terms, ranging from the costs to those directly impacted to criminal justice and medical system expenses and also the monetary costs of increased fear and avoidance. And that is just the price of a gun murder. The human and economic costs of all gun crime runs far higher.

For any city facing high rates of crime, preserving life by preventing lethal or near-lethal violence must be at the top of the policymaking agenda. Progress should be measured in clear, concrete terms: fewer homicides and non-fatal shootings. And despite what their political consultants may say, leaders should commit to tangible reductions in these measures. Annual reductions of 10% are an impactful yet realistic goal.

To achieve this, law enforcement agencies must keep a consistent focus on preventing violence, not just making lots of arrests for minor infractions. Effective management also means rewarding officers for outcomes like reduced victimization, rather than outputs like the number of pedestrian or car stops they make. Similarly, non-enforcement partners such as community-based service providers should maintain a focus on anti-violence outcomes, not outputs such as services delivered.

Next, city leaders must remember that gun violence concentrates among small sets of key people, places and groups, and must focus their engagement on them. They should begin with a rigorous problem analysis like the one completed in Oakland, using police and hospital data to map out the locations and social networks where violence clusters. Analyses like these are critical to creating a shared understanding of a city’s violence challenge and guiding collaborative efforts.

Based upon the analysis, city leaders must create a strategic plan for engaging key people and addressing key locations. Supports and services must be offered so disconnected, at-risk community members have something better to say “yes” to, but it must also be made clear that further violence will not be tolerated. Police can disrupt cycles of violence to cool identifiable “hot spots,” but such short-term actions must be supplemented by investments to change the nature of these violent locations and the communities in which they are located.

In communities impacted by gun violence, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder can be more common among residents than among veterans of the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, or Vietnam. Because of this, it is crucial for city leaders to emphasize healing with trauma-informed approaches. Agencies working with victims and survivors should be careful to deliver services in ways that do not retraumatize their clients. Law enforcement officers also experience trauma and can benefit from such approaches as well.

Also, without clear and consistent buy in from city leaders, plans tend to stay on the shelf, and the deadly toll mounts. To avoid this, every city suffering from high rates of violent crime should have a permanent office dedicated to violence reduction operating inside the mayor’s office, with senior leadership reporting directly to the mayor. These units, such as the Office of Gang Reduction and Youth Development (GRYD) in Los Angeles, should act as the hub for a city’s anti-violence efforts. The office leader must report directly to the mayor, as anything else will significantly diminish performance and long-term viability. These units must also be sustainably staffed and substantially funded in order to be successful.

Finally, cities must hold themselves fully accountable using rigorous research and reliable data. Whatever strategies are chosen, they should be backed up by evidence of effectiveness. Then, those strategies must be monitored to see if they actually stop violence and save lives. Leaders must embrace a learning culture that is able to recognize when strategies are not working and shift course—without starting over from scratch. Data must be gathered and research partners should be engaged early to assess performance, working in close consultation with police and community partners. Without this careful, continuous and honest evaluation, even the best-intentioned effort can go off track, and everybody loses.

We don’t have to sit on our hands and wait for the legislative impasse in our statehouses and in Congress to break—what matters most happens in our cities and communities. If we can push past our toxic politics to collectively embrace the actions outlined above, progress on gun violence is not just possible, but likely. In the cities that demonstrate courage and commitment, shootings and killings will wane. But we can’t stop there.

While saving lives begins with curbing violence, it also requires us to address the ugly legacies of segregation and disinvestment that lead to violence in the first place. As we work to help impoverished communities achieve a measure of safety and stability in the short term, we must also help them thrive with investments in education, employment, health, housing, and transportation over the long run. We must bring opportunity back to these neighborhoods—not just to restore peace, but because it’s the right thing to do.

On January 3rd in Philadelphia, Councilmember Kenyatta Johnson released a statement about the record-setting violence of last year. He offered many good ideas, but no firm plan. He concluded, “Enough is enough. We must do better.” We must all do better, and we can, if we put politics aside and follow the right roadmap.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com