In the aftermath of the insurrection a year ago at the U.S. Capitol, many leading historians drew parallels between the violence and the Reconstruction era, the period of political revolution directly following the American Civil War.

“The events we saw reminded me very much of the Reconstruction era and the overthrow of Reconstruction, which was often accompanied, or accomplished, I should say, by violent assaults on elected officials,” Eric Foner, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and author of Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, said in an interview with the New Yorker published a week later.

Scholars say studying the aftermath of the Civil War can help put in context many of the most seminal events in the U.S. in recent years, from the brutal murder of George Floyd by police in 2020 to the voter suppression laws enacted after Black voters played a big role in helping Joe Biden and Kamala Harris be elected President and Vice President in 2020. But despite the timeliness of the era in today’s climate, many students in American schools will not get a full education on Reconstruction until they get to college.

In social studies standards for 45 out of 50 states and the District of Columbia, discussion of Reconstruction is “partial” or “non-existent,” according to historians who reviewed how the period is discussed in K-12 social studies standards for public schools nationwide. In a report produced by the education nonprofit Zinn Education Project, the study’s authors say they are concerned that American children will grow up to be uninformed about a critical period of history that helps explain why full racial equality remains unfulfilled today.

(The Zinn Education Project, a website with free, downloadable lessons and articles about history topics, is an outgrowth of Howard Zinn’s 1980 A People’s History of the United States, which helped popularize an approach to studying history from the bottom-up and incorporating the often overlooked histories of people of color.)

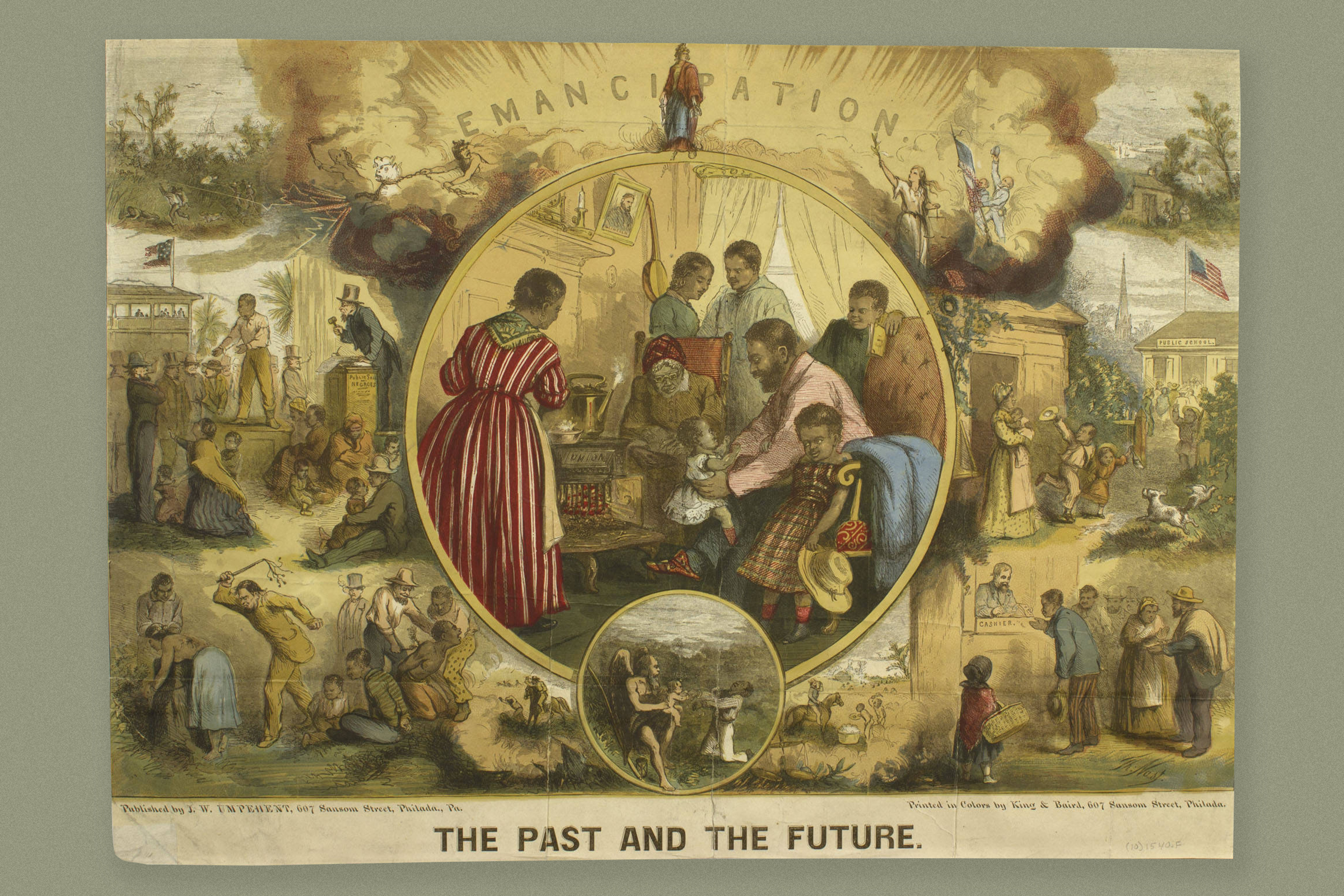

The Reconstruction era—a period from roughly 1865-1877—saw immense social, political, and economic growth as the U.S. worked to rebuild society in the aftermath of the Civil War. In this period, three constitutional amendments were ratified: the 13th Amendment (1865), which abolished slavery; the 14th Amendment (1868), designed to ensure equality before the law; and the 15th Amendment (1870), which barred discrimination in voting “on account of race.” These advances helped facilitate a rise in Black officeholders and Black voters.

But in the late 1870s, the federal government pulled out of its role helping to enforce Reconstruction policies, per a deal struck by congressmen to settle the disputed 1876 election in which Ohio Gov. Rutherford B. Hayes won the presidency in exchange for the removal of federal troops in the South. Enforcement of Reconstruction policies was left up to state and local governments, paving the way for Jim Crow-era state segregation laws that wouldn’t be declared unconstitutional for roughly another century.

Read more: How Reconstruction Still Shapes American Racism

For the Zinn Education Project’s report, historians Ana Rosado, Gideon Cohn-Postar, and Mimi Eisen evaluated state social studies standards by looking for their inclusion of noteworthy moments of the Reconstruction period. Their criteria ranged from instruction on local governments denying Black people the ability to own land to violence carried out by white supremacist terror organizations like the Ku Klux Klan.

(Among the most concerning phrasing the researchers found was in Georgia’s 8th grade social studies standards, which expect students to “compare and contrast the goals and outcomes of the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Ku Klux Klan,” suggesting a moral equivalency between the two.)

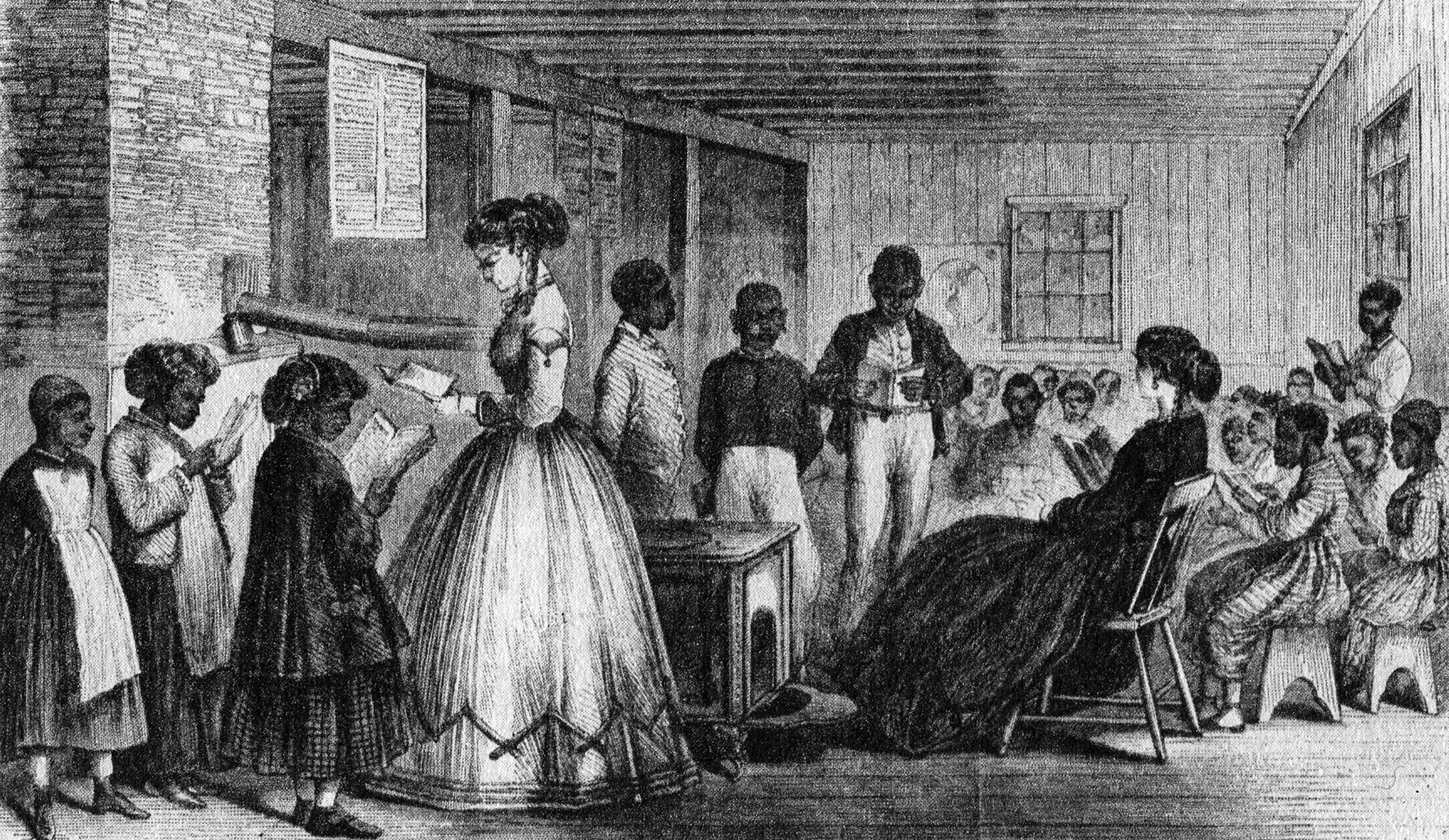

They were looking for mentions of the Freedmen’s Bureau, formed to provide aid to the 4 million formerly enslaved people after the Civil War; for stories of Black people mobilizing for political participation and the establishment of clubs like the Union Leagues; for discussion of Northern industrialists’ power in the South and Black struggles for land ownership and labor rights. And they wanted to see the legacies of Reconstruction addressed, such as Reconstruction-era schools as a basis for public education today to the more sobering, like Jim Crow-era racism’s legacy in policing and prisons and disparities in health, wealth, and housing.

Overall, the researchers found K-12 social standards didn’t cover most of these topics. In interviews, teachers said they had barely learned about the period themselves and would need more professional development to feel comfortable teaching it in-depth. Educators were also concerned that the recent spate of state laws prohibiting the teaching of “divisive concepts” will limit instruction on the full history of racism in America.

Read more: From Teachers to Custodians, Meet the Educators Who Saved a Pandemic School Year

“The message is more that the education system in this country across the country is failing to teach Reconstruction sufficiently and that everyone can do better,” says Eisen. “We’re hoping to encourage readers to advocate for more attention to Reconstruction and K-12 curriculum in the classroom.”

While many states expected students to know why Reconstruction failed, the report found less of a focus on the era’s successes—or efforts to help ensure Black Americans could be full citizens. The scholars say viewing Reconstruction only by its failure is problematic. The researchers also found the standards tended to focus on events on the federal level, presidential and congressional actions, which can skew teaching towards the actions of white people at the expense of stories of Black Americans’ resilience, whether at the community level—with the building of mutual aid organizations and church communities—or with regards to individuals like Octavius Catto of Philadelphia who fought against segregation in baseball and was shot to death in 1871 after helping organize voter registration drives.

Jesse Hagopian, a high school teacher in Seattle and Zinn Education Project staffer who helped develop the report, says Black progress during Reconstruction is key to imagining a more equitable future. As he explains the report’s significance, “If children don’t grow up learning the incredible strides forward that were made in that time period, then it’s hard to imagine freedom today. And so that’s what I think we lose when we don’t teach it properly.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com