Moulton, a Democrat, represents Massachusetts's 6th Congressional District. He sits on the House Armed Services Committee and the Select Committee on China. He served as a Marine Infantry Officer in Iraq.

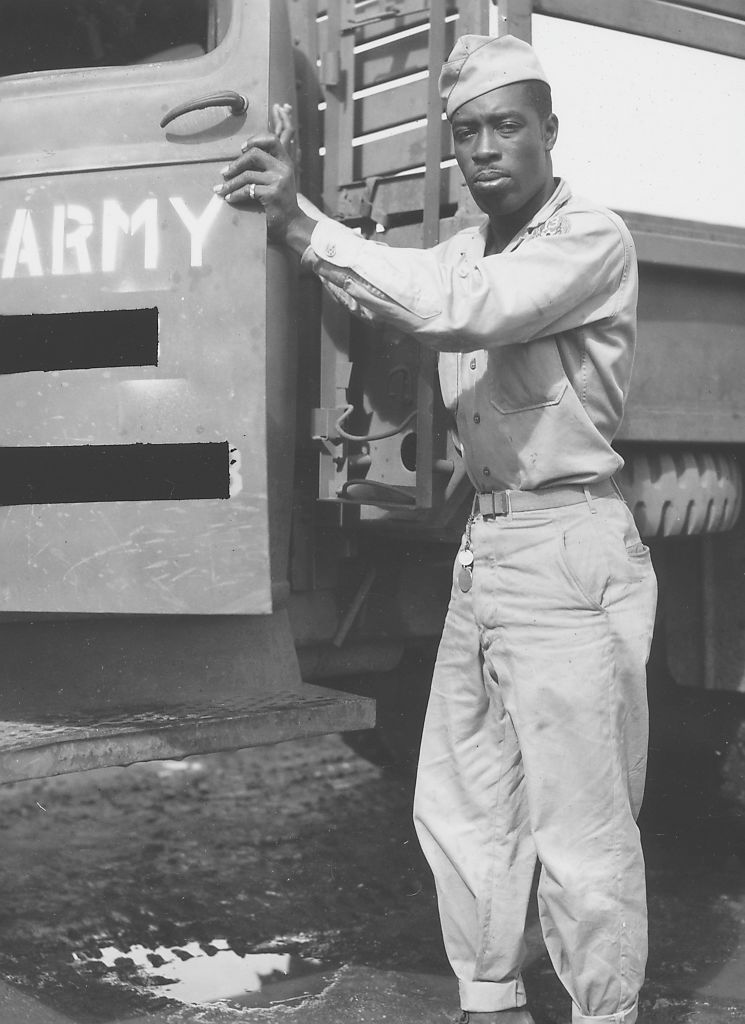

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, 1.2 million black servicemen and women were among the 16 million Americans who answered the call to defend our country and protect democracy abroad. The irony of fighting a war to defend democracy—in segregated ranks—wasn’t lost on them, but they believed in America’s promise. And they believed their commitment to the country they loved would pay off. But when they returned home, much of that promise was denied to them.

One of them, Sgt. Joseph Maddox was accepted at Harvard, but there was one problem: He was Black. So, the Veterans Affairs department denied his GI Bill tuition “to avoid setting a precedent.” Sgt. Isaac Woodard, another Black veteran, fared worse. Newly discharged from active duty and still in uniform, Sgt. Woodard was hauled off a bus on the way to his home in South Carolina by a local police chief who beat him and left him blind.

Maddox, Woodard, and thousands of Black soldiers watched as returning white soldiers enjoyed the full benefits of the GI Bill, gaining access to quality universities that led to well-paying jobs, securing loans to buy houses in the suburbs with their families, and starting businesses that grew in the postwar economy. Ultimately, white veterans gained substantial wealth for themselves and their families that has lasted generations.

At the same time, discriminatory policies and prejudiced state and local officials barred Black families from fully accessing those same benefits. Racially biased lending practices, known as redlining, prevented many Black veterans from accessing home loans. Segregation and quota systems prohibited many of them from attending well-funded, predominantly white universities. Many Black veterans instead went to segregated, underfunded black institutions and vocational schools. These systemic inequities limited their opportunity to accumulate wealth.

For example, in the summer of 1947, only two of the 3,299 VA-guaranteed home loans in 13 Mississippi cities went to Black borrowers despite Blacks accounting for half the population of the state. In New York and the northern New Jersey suburbs, fewer than 100 of the 67,000 mortgages insured by the GI Bill supported home purchases by non-whites.

The original GI Bill, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, was a race-neutral bill intended to serve both as a gesture of gratitude and a substantial economic benefit to all the brave American heroes returning from war. However, Black veterans were systemically shut out from the GI Bill and the prosperity of the postwar period. While the bill on its face did not explicitly exclude Black veterans, its implementation did; and this legacy of discrimination must be addressed.

Most Popular from TIME

The GI Bill remains one of the largest investments America has made in its millions of veterans. It is credited with building out America’s expanding middle class and boosting our nation’s economy. Two significant ways to build wealth in this country are through education and housing—two major pillars of the original GI Bill from which Black WWII veterans and their families were excluded.

As it stands today, no progress has been made in reducing income and wealth gaps between Black and white households over the past 70 years. In fact, the net wealth of a typical Black family in America is around one-tenth that of a typical white family. The simple truth is that America did not keep its promise to all of the “Greatest Generation” and it’s time we make it right.

That’s why we introduced The Sgt. Isaac Woodard, Jr. and Sgt. Joseph H. Maddox GI Bill Restoration Act of 2021, more simply known as the GI Bill Restoration Act. Introduced last month, along with our colleague in the Senate, Senator Reverend Rafael Warnock, this legislation would restore education and housing benefits to Black WWII veterans and their descendants alive at the time of the bill’s enactment. It would also create a panel of independent experts to study inequities in how benefits are administered to women and people of color.

One of us is a veteran who used the G.I. Bill to go to school after the Marine Corps and would not be a sitting United States member of Congress without it. One of us remembers the blinding of Isaac Woodard and represents communities in Congress with a significant number of families impacted by the inequitable distribution of GI Bill benefits.

Our generation didn’t commit this wrong, but we should be committed to making it right. The GI Bill Restoration Act acknowledges and makes amends for our nation’s failure to honor the promise we made to all our nation’s veterans. We look forward to leading the effort to address one of the greatest racial justice issues of our time.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com