Among the policy proposals included in the “Build Back Better” Act championed by the Biden administration and congressional Democrats is legislation the White House describes as “the largest investment in childcare in the nation’s history.” The sweeping social policies would include universal and free prekindergarten and expanded child tax credits; child care activists back the proposals to limit child care costs to no more than 7% of most families’ income.

But there is an element of déjà vu to the timing of the negotiations on a landmark childcare bill this week, and the rhetoric surrounding it—particularly when Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) denounced the bill’s child care provisions as “a toddler takeover” on the Senate floor:

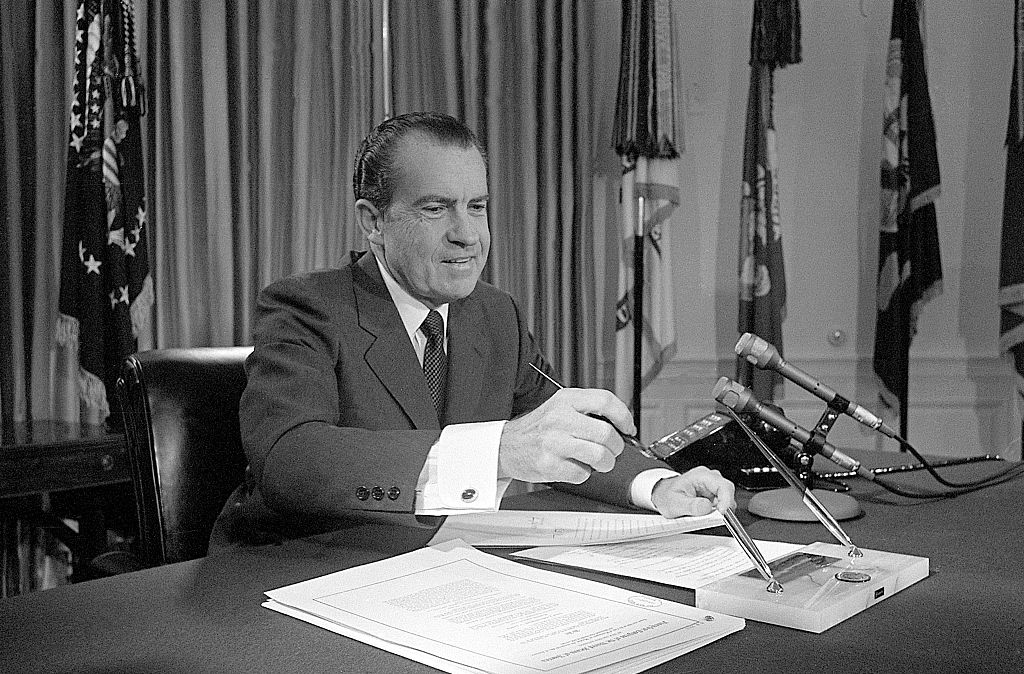

Fifty years ago on Dec. 9, 1971, President Nixon vetoed another landmark bill, the Comprehensive Child Development Act (CDA), which would have created federally-funded public childcare centers across the U.S. And scholars say the origins of childcare as a hot button political issue can be traced back to the pushback Nixon faced back then.

Nixon had initially talked up childcare as a key part of his legislative agenda. “So crucial is the matter of early growth that we must make a national commitment to providing all American children an opportunity for healthful and stimulating development during the first five years of life,” he said in a Feb. 19, 1969, statement to Congress.

Sponsored by Senator Walter Mondale (D-MN), the CDA would have provided universal childcare to three and four year olds. The poorest Americans wouldn’t have to pay at all, but the middle class and more wealthy parents would be charged on a sliding scale depending on their income. It was considered “one of the most significant social legislation” of the congressional session, TIME reported in its Dec. 20, 1971, issue.

“The CDA would have been the largest federal investment in childcare,” says historian Anna K. Danziger Halperin, an expert on the history of child care and fellow at the New-York Historical Society.

Read more: The Child Care Crisis

And yet, conservatives mobilized to kill the CDA immediately. Their arguments reflected Cold War anxieties. Many were opposed to Nixon’s planned trip to China in 1972, so they were quick to call the bill communist. Though the bill’s programs like day care facilities, night-time childcare, and psychological services were voluntary, conservatives feared such social services were akin to the government raising children and trying to control families. Conservative Democrat from Louisiana John Rarick called it “the most outlandish of the Communist plans,” according to Elizabeth Rose’s The Promise of Preschool: From Head Start to Universal Pre-Kindergarten. When the CDA passed in the House, conservative pundit James Kilpatrick wrote, “Child Development Act—To Sovietize Our Youth.” Several parent groups sprouted up on the grassroots level such as Parents of New York United, which criticized the effort to “federalize America’s children,” while Iowans for Moral Education leaflets asked “Whose Children? Yours or the State’s?”

The CDA’s opponents were successful. The bill passed the House and the Senate, but Nixon vetoed it on Dec. 9, 1971. Nixon’s advisers deemed the veto necessary to ward off a 1972 primary challenger.

“For the Federal Government to plunge headlong financially into supporting child development would commit the vast moral authority of the National Government to the side of communal approaches to child rearing over against the family-centered approach,” Nixon said in a statement explaining the rationale behind his veto, singling out Title V, its child development programs. “Though Title V’s stated purpose, ‘to provide every child with a full and fair opportunity to reach his full potential’ is certainly laudable, the intent of Title V is overshadowed by the fiscal irresponsibility, administrative unworkability, and family-weakening implications of the system it envisions. We owe our children something more than good intentions.”

In fact, that same month, he signed the 1971 Revenue Act which essentially facilitated the system that exists today relying on private child care arrangements, with tax deductions to help the middle and upper class families and often inadequately-funded public child care supports for the poorest families.

“That was a moment when we could have had a national childcare system, and it failed,” Rose tells TIME, arguing that Nixon’s veto in turn galvanized “the emerging conservative movement’s focus on ‘family values.’”

(Former Indiana Congressman John Brademas, a CDA co-sponsor, said as much in a 1997 interview looking back at the early 1970s conservative opposition to national childcare. “Those attacks poisoned the well for early childhood programs for a long time—indeed, ever since.”)

Fifty years later, childcare activists in the U.S. are still fighting for larger government childcare subsidies and higher wages for childcare workers, many of whom live on the poverty line.

Childcare needs have only increased as the rates of women in the workforce have increased; between 1975 and 2019, the rate of women with children under 3 participating in the labor force nearly doubled. Now women make up the majority of the workforce at 50.04%, and America spends less than 1% of its GDP on child care. Low income parents spend more than a third of their income on child care costs, and more than half of families live in a “child care desert.”

“Nixon might as well be in the office,” says C. Nicole Mason, president and chief executive officer of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. “It might as well be 1971 because the arguments, the rhetoric around childcare—not much has changed, unfortunately.”

Read more: The Rise of the ‘Carebnb’: Is This Home-Based Model the Future of the Childcare Industry?

The CDA came at a time when women were increasingly entering the workplace and at the height of the women’s liberation movement. Voicing support for the legislation in congressional hearings, leading feminist activist Rep. Bella Abzug reminded her colleagues that the bill was not only a “children’s bill” but also “a woman’s bill.”

“For the past half a century women have been paying the price for a veto that was grounded in fear mongering,” Melissa Boteach, Vice President for Income Security and Child Care at the National Women’s Law Center tells TIME. “The state of childcare today in the United States is completely unsustainable and ridden with gender and racial inequities.”

What’s new about the current conversation about childcare amid COVID-era work-from-home setups is that more people across racial and class lines are seeing how much the system needs to be overhauled. As Halperin puts it, “There hasn’t been a strong social movement pushing for child care since the early 1970s, but as more people become attuned to how absolutely essential it is for child development, women’s equality, and the economy as a whole, perhaps we’ll see that change.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com