On Nov. 9, Cuban journalist Elaine Diaz was trying to send out a newsletter to the subscribers of Periodismo de Barrio, her watchdog news site covering human rights issues on the island, when she got an error message on her screen.

The U.S.-based service she had been using, MailChimp, had suddenly and unexpectedly eliminated her account. “They did it without prior warning, for being based in Cuba,” she wrote on Twitter. “It’s not the first Cuban outlet to go through this experience. Shameful.”

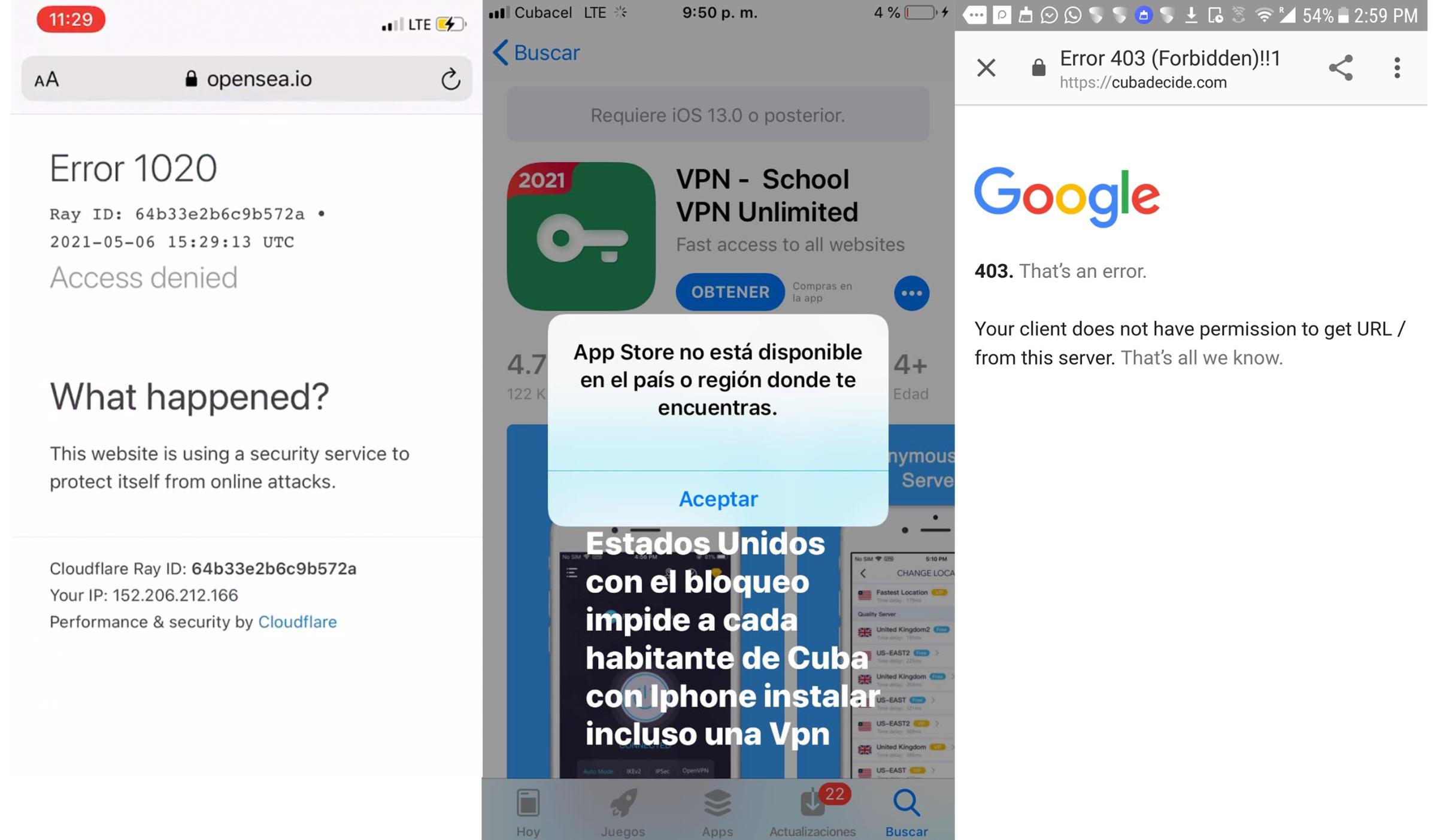

As Internet access has exploded on the island, an increasing number of Cuban journalists, activists, dissidents and artists find themselves locked out of the online platforms and services used by the rest of the world—not by their communist government, but due to restrictions imposed on American companies by the broad, 60-year-old U.S. embargo. In recent years, they have been abruptly blocked from cloud services, file transfer sites, social media managers, editing software, development apps, video calling, free education platforms and NFT marketplaces. It not only shuts them out of the global digital economy, several young Cubans tell TIME, it also makes it harder to create content and reach a wider audience.

The restrictions come on top of the Cuban government’s own tight grip on Internet access for its citizens through the state-owned telecommunications monopoly, ETECSA, which blocks news websites deemed critical of the regime. The agency also restricted access to social media platforms in the wake of historic protests over food and medicine shortages in July, with some calling on President Miguel Diaz-Canel to step down.

The two factors have combined to hit the heart of Cuba’s protest movement. The summer protests, as well as the San Isidro demonstrations that preceded it last year, were spearheaded by young artists who rely on digital platforms to disseminate information and express and organize themselves online. As a result, the blunt instrument of the decades-old embargo is inadvertently stifling the very freedom of expression and robust civil society that the U.S. government seeks to support in Cuba, experts say, as U.S. companies try to avoid running afoul of the law.

“It’s a classic case of our own sanctions boomeranging and biting us in the ass,” says Ted Henken, a professor of Latin American studies at Baruch College who has written a book on Cuba’s digital revolution. “The embargo is so ill-targeted and its enforcers know little about the island’s emergent digital civil society.”

Although Mailchimp ultimately reinstated Diaz’ account after she went public, that was a rare exception, according to Cuban artists and activists who spoke to TIME. (A Mailchimp spokesman told TIME the service “operates in compliance with all applicable laws and regulations” but did not clarify how Diaz’ circumstances changed.) There are at least 107 popular tech sites, software and web services restricted from being used in Cuba, according to a compilation by Cuban programmers on Github, a site for sharing code. These services list restrictions on users in Cuba, Iran, North Korea and Syria on their websites, citing U.S. law.

“As time goes by, more and more websites and services are being blocked for Cubans,” says Gabriel Guerra Bianchi, a Havana photographer and artist. Like many Cuban artists and activists who had started to build a community around digital art, he was frustrated when OpenSea, a popular website for selling digital items, blocked Cuban users in May citing the embargo, locking them out of one of the largest marketplaces for non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

“Sometimes one doesn’t even know where these [blocks] are coming from—whether from here or from there,” Bianchi said. He says he doesn’t blame services like OpenSea, which he said expressed regret to their community of Cuban users. “It’s not out of bad faith from these companies, but rather it seems to be part of their security protocols to avoid future problems with the U.S. State Department.”

Cubans have lived with the impact of the U.S. embargo for generations. President John F. Kennedy imposed a near-total trade embargo on the country in 1962 after Washington’s failed attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro, citing “the subversive offensive of Sino-Soviet Communism” the regime was aligned with. As a result, Cuba, which depended heavily on trade with the U.S., became reliant on the Soviet Union, and later Venezuela, for economic and military aid.

But the embargo’s restrictions on U.S.-based services have gained new urgency as web access has expanded to more Cubans. Internet usage in Cuba grew dramatically in the wake of the historic détente in 2014, when President Barack Obama and Raul Castro agreed to re-establish diplomatic relations, leading to the easing of many restrictions on business with and travel to Cuba, as well as an influx of U.S. dollars. Although Cuba only allowed full Internet access on mobile phones in 2018, more than four million citizens on the island—over a third of the population—now access the web on their smartphones.

The relationship between the two countries deteriorated again under Trump, who promised to reverse Obama’s measures and toughened the embargo by imposing over 240 sanctions during his four years in office. President Joe Biden, despite vowing during his presidential campaign that he would restore Obama-era policies of engaging with the Cuban regime, so far has not moved to ease the restrictions.

The complicated web of regulations, trade restrictions and sanctions that comprise the embargo forbid U.S. companies from providing any type of service to Cuba. While there are exceptions for some telecommunications services that expand actual Internet access on the island and “directly benefit the Cuban people,” according to the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), this does not include most web services, which would only be able to provide services to Cuba under a special license. Confusion over how to interpret these regulations has led many U.S. platforms and companies to abruptly pull their services in recent years, rather than risk violating the embargo.

Read more: Food Shortages, COVID-19, and Instagram: The Driving Forces Behind the Cuba Protests

Access has been tightening for years. In 2014, Coursera, a California-based online education platform that offers free classes, suddenly blocked users from Cuba as well as other sanctioned countries from logging into their accounts. The company said in a statement at the time that while export control regulations for educational services had “been unclear,” they had received information from the State Department and OFAC that allowing users in these countries to access their services was in violation of U.S. law. Similarly, link-shortening website Bitly suddenly stopped working for Cuban users in 2016, leading to a wave of broken links across Cuban websites.

In 2017, Cuban human rights activist Rosa María Payá saw an error message for her website “Cuba Decide,” an initiative calling for a national plebiscite on free elections. She found that the site had been blocked not by the communist government but because it was using Google’s Project Shield, a DDoS protection service that works with journalists, human rights organizations and elections monitoring sites. In a tweet, Payá called it “the error with which Google joins censorship in Cuba.” Google said at the time the site was being blocked due to compliance with the U.S. embargo. “I would like to know what provision of the embargo forces Google to block an initiative to promote freedom of expression?” Payá asked the Miami Herald.

Four years later, the list of web services used to create and disseminate content and organize online communities has only grown—and with it, the sudden errors that Cuban users encounter. Google blocks access in Cuba to a variety of services that might run afoul of the embargo, such as Google Cloud, Google Developers, Google One and Google Play, according to the list compiled by Cuban programmers. Some of the other apps that are blocked are Adobe, Android Developers, Gitlab, IBM software, Intel, Java, Oracle, Zoom, and a host of payment apps that are necessary to participate in much of the digital world.

PayPal, for instance, which will allow transactions that mention the words “bomb” or “cocaine,” will block any transaction with the word ‘Cuba’ in it. (When a TIME reporter tried to send another user in the U.S. $1 with the note “Cuba Libre” on Nov. 17, PayPal immediately restricted their account and put the transaction under review.) Paypal’s terms of service note that its services may not be used by residents or nationals of “any country subject to United States embargo or UN Sanctions.”

One day last June, Claudio Pelaez Sordo, a Cuban photo and video-journalist who works for independent news outlets, woke up to find himself no longer able to access WeTransfer, a file transfer service that had become indispensable among many Cuban artists and content creators. Unlike Google Drive, it didn’t require users to register for an account, and allowed them to send files up to 2 GB.

“The U.S. government prohibits the provision of certain products and services to specific countries. What this means is that regrettably we are unable to provide our services to you,” the error message read. Although headquartered in Amsterdam has offices in New York and Los Angeles. WeTransfer did not respond to TIME’s request for comment.

“This adds itself to the long list of sites and platforms that [we] can’t access as part of the economic blockade against Cuba,” Pelaez Sordo posted on Facebook on June 10. But “if there’s something the Cuban government has taught us, it’s how to always find a way around it,” he wrote, adding the hashtag #righttolivewithoutblockade.

Read more: Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, one of the leaders within Cuba’s San Isidro movement

Young Cubans have increasingly relied on VPNs to work around these restrictions, in order to access everything from news websites blocked by the Cuban government to online services and apps blocked by U.S. sanctions. But low-cost VPNs tend to work slowly, according to people who spoke to TIME, forcing Cubans to spend their money on expensive ones if they want to access or use services that are free to access in the rest of the world.

This has especially frustrated some young artists as Havana has become an unlikely hotspot for crypto art in recent months. Cuban artists have launched several art collections through NFTs, which not only open up new sources of income in their devastated economy but serve as outlets of protest and expression.

“Oh come on!!!! Really!??” tweeted Bianchi, the Havana photographer and artist, when OpenSea blocked him in May. “Cuban artists can’t have access. We are creators! Give us a break!” (An OpenSea spokesman acknowledged to TIME the service had been blocked for Cuban users due to the U.S. sanctions). When sympathetic followers from around the world suggested VPNs to bypass the block, Bianchi explained the reality: even many slow, cheap ones are out of reach for many Cubans.

“This $10 dollars a month is a 10-day salary in Cuba,” he replied on Twitter. “Not only that, we don’t have credit cards in Cuba to pay, or bank accounts.”

The complicated web of U.S. trade restrictions under the embargo, as well as the whiplash of the recent opening and closing of U.S.-Cuba relations during the Obama and Trump administrations, has deterred American companies and platforms from trying to find a way to operate in Cuba, experts say.

“I’ve worked with a lot of clients over the years who take a very conservative approach and decide they don’t want to run that risk,” says Doreen Edelman, a partner at Lowenstein Sandler who chairs their global trade and policy practice, adding that this is especially true for the start-ups who run many of these services. “They’re not going to want to pay for legal fees for stuff like this, so they’ll just follow the embargo and be done with it.”

But while the blanket Cuba embargo dates back 60 years, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control has recently been “much more surgical” in its approach to sanctions, says Laura Fraedrich, senior counsel at Lowenstein Sandler’s global trade and policy team. She points to sanctions against certain people and specific activities in countries like Russia and Venezuela. “It’s targeted at people who are in or have been in the government, and you really wonder why we couldn’t go to something like that for Cuba to mitigate some of these secondary and tertiary effects.”

Unsurprisingly, the Cuban government has used the blocking of these services as part of their broader criticism of the U.S. embargo. In a report to the U.N. Secretary-General last year, it outlined how the embargo’s impact on online communications had resulted in Cuban representatives having trouble accessing or participating in virtual U.N. meetings related to the COVID-19 pandemic, since digital platforms like Zoom and Microsoft Teams are restricted in Cuba. (The State Department referred questions to OFAC, which did not respond to TIME’s request for comment.)

It’s a rare point of agreement between the communist regime and some young Cubans. “Solidarity or just appearances?” Rubén Martínez Rojas, who lives in Havana, wrote in a Facebook post in August. “It would be interesting to know how it is possible that the U.S. is so interested in a free access internet for Cubans but prevents us from accessing digital platforms such as WeTransfer, OpenSea, Adobe and dozens of others that are accessed by the rest of the world, adding obstacles to our human development.”

Though a group of Republican politicians, including Florida’s Gov. Ron DeSantis and Sen. Marco Rubio, have been clamoring for the Biden Administration to do more to facilitate Internet access in Cuba to promote democratic values on the island, Rojas pointed out that goal is at direct odds with the impact of the embargo.

The U.S. restrictions are preventing Cubans from creating iCloud accounts or installing applications from the App Store, necessary for anyone wanting to use an iPhone, forcing them to pay for expensive workarounds, he wrote. “No U.S. senator is worried about resolving these issues caused by this decades-long blockade which affect every inhabitant of Cuba.”

Lawmakers who have called for expanded Internet access for Cuba placed the blame squarely on the Cuban government. “The U.S. sanctions specifically do not apply to telecommunication,” a Rubio spokesperson told TIME. “It is the regime that is blocking access to it and reporting otherwise is to parrot their propaganda.” His office did not respond to the fact that many of the services in question cite the embargo as the reason for their restricting service to Cuba.

Both U.S. technology policy towards Cuba and the general policy under the embargo are beset by the same internal contradictions, says Henken, the professor at Baruch College. While their aim is to isolate or target the Cuban government, they often impact the people they are designed to support and empower, working against U.S. interests in the country, he says. “The irony is that the same U.S. politicos that support granting free and uncensored access to the internet for the Cuban people also support an embargo which puts those connections in legal and financial jeopardy,” he says.

He cites the example of Cuban opposition group Archipelago, which was behind an attempted Nov. 15 protest and relies on online activists. The November demonstrations were largely suppressed by the government, but could have easily been affected by the U.S. embargo, he says.

“Just imagine if a group like Archipelago would have had one of its essential social media accounts canceled right during the planned protest, due not to the Cuban regime’s internal blockade on the free flow of information but due to the ham-handed and woefully imprecise U.S. embargo.”

—With reporting by Abby Vesoulis

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Vera Bergengruen at vera.bergengruen@time.com