While a senior at Tennessee State University (TSU) in 2002, Keeda Haynes agreed to receive multiple packages for her then-boyfriend. He told her that the deliveries were for a cell phone and pager business. As it turned out, the packages actually contained marijuana.

Unbeknownst to Haynes, her boyfriend was being watched by the police. By association, she was too—and because Haynes had signed for his packages, she was arrested.

During her subsequent trial, Haynes pleaded not guilty and consistently stated she was unaware of the drug shipments. She was acquitted of conspiracy to distribute marijuana but she was convicted of aiding and abetting a conspiracy. Due to Tennessee’s mandatory minimums for drug possession, she was sentenced to seven years in prison.

After an appeal, her sentence was reduced; she spent four years in federal prison before her release in 2006.

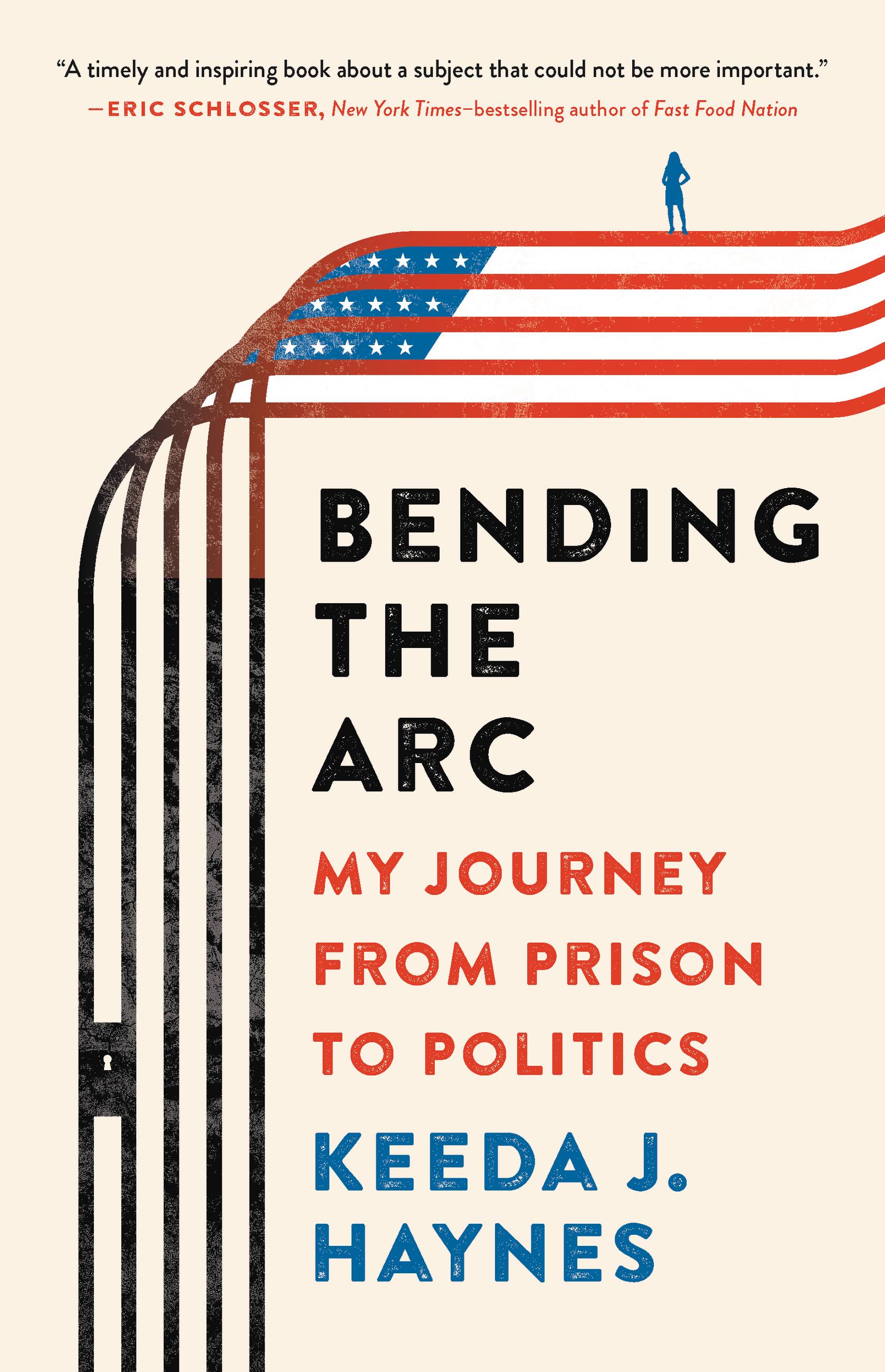

While in prison, Haynes studied for the LSAT—she had already graduated from TSU with a degree in criminal justice and psychology by the time she was incarcerated—and, after her release, went to law school. Her tumultuous journey through the criminal justice system had inspired a career change as well as a larger personal reckoning; Haynes later became a public defender. In the summer of 2020, she ran for Congress (though she did not win the Democratic primary). Haynes’ new book, Bending the Arc: My Journey from Prison to Politics, details this journey—as well as the steps ahead.

Speaking with TIME, Haynes discusses her experiences, the racial and criminal justice awakenings that happened in 2020 and where the movement for court reform goes from here.

TIME: Throughout Bending the Arc, you talk about how your experiences give you unusual insight into the criminal justice system. Why do you think that perspective is so important?

Haynes: There are not a lot of lawyers who have actual lived experience of personally dealing with the criminal legal system. I’ve experienced it being [incarcerated], and I’ve experienced it as a public defender. When you look at it from all sides, you realize that it is a system that operates one way for the white and wealthy and another way for the rest of us. It is a system that targets Black and brown and low-income communities. It perpetuates poverty, and it is designed to break you down.

How did your prison sentence change you?

I majored in criminal justice and psychology. I had done a lot of research about the world of drugs, and particularly about cocaine and crack cocaine [sentencing] disparities. But it wasn’t until I actually experienced prison myself that I really understood.

I originally wanted to be a criminal defense lawyer. [But when] I was incarcerated and heard the stories of other women and how they felt that their attorneys—most of whom were public defenders or court-appointed attorneys—did not do enough for them, I said I wanted to be a public defender. Public defenders are overworked and underpaid.

I was fortunate enough to have a private lawyer when I was going through the system. I wanted to be able to provide the same level of representation that I got to people that can’t afford that. I wanted to do everything in my power to fight for my clients; I felt like I was carrying my personal experiences of [being incarcerated] in my workspace.

When you look at everything that’s happened after the murder of George Floyd and the reckoning that has occurred around the criminal justice system, what stands out to you the most?

We’ve been talking about these issues for years. Black people have been saying these things for years. Black people have been sounding the alarm [for years]. This country was just pressing the snooze button.

With George Floyd’s murder, [more] people came to the realization that the criminal justice system doesn’t operate in a silo. It intersects with redlining and the lack of affordable housing; with Black and brown people being unemployed or underemployed; with the lack of funding for our education system, and particularly for the schools that are in Black neighborhoods. It made people realize that we needed to be dealing with all of these issues.

But in terms of criminal justice legislation, negotiations in Congress over the George Floyd Policing Act—a proposed bill to address policing practices and law enforcement accountability—fell through earlier this year. Where does the country go from here?

If we only look at this as a criminal legal issue, then I think that we’re being short-sighted. But in order to pass legislation, we’ve got to have people [in a position to address] what we are seeing in our communities. If we don’t have the voting power that we need in order to elect people into these positions, then nothing is going to change.

I really think that felony disenfranchisement is the ultimate voter suppression. You have over 5 million people in this country who can’t vote because of a felony conviction on their record. And when you really start to break down the numbers, and see who is actually impacted by the felony disenfranchisement laws, it is Black and brown people. That speaks volumes.

What keeps you motivated when change sometimes seems so far away?

This is a collective thing—a collective fight that we’re in. We can’t give up. I think as long as we continue to stay focused on what we’re trying to do—to reshape the criminal justice system—learn from our setbacks and regroup then I think we will eventually get to where we need to be, which is to move the system towards [actual] justice.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Josiah Bates at josiah.bates@time.com