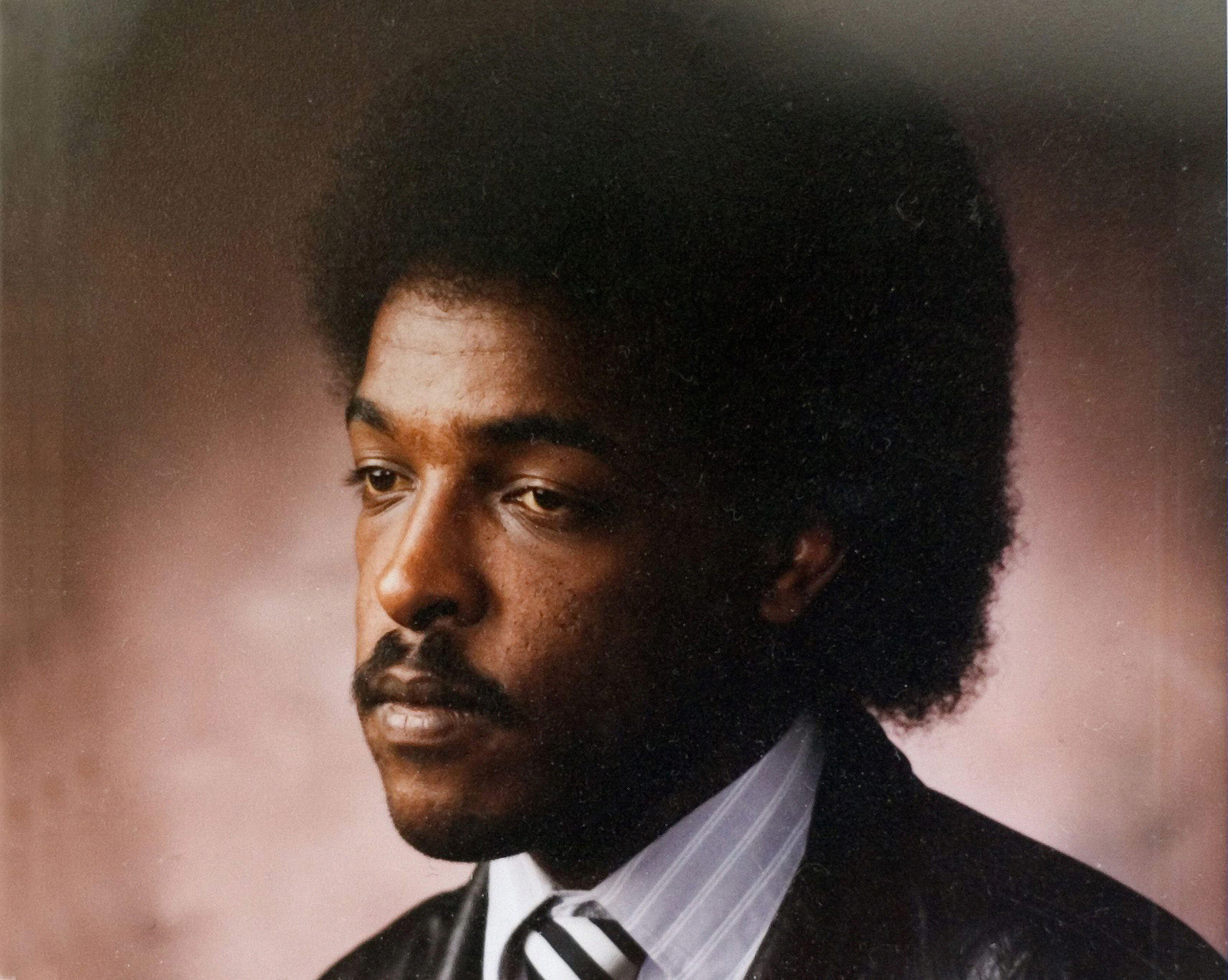

In 2001, the Eritrean government shut down the entire independent press. The Swedish-Eritrean journalist Dawit Isaak, a prolific writer and courageous journalist with Setit, Eritrea’s first independent newspaper, was arbitrarily detained, held incommunicado, and denied access to family, consular assistance, and the right to counsel—effectively, an enforced disappearance. The “crime”? Setit had published an open letter calling for democratic reform signed by fifteen members of Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki’s government.

Isaak and his colleagues are the longest detained journalists in the world today. Eleven of the open letter’s signatories were detained along with them, and some have already died in prison. No independent media has operated in Eritrea since Isaak’s arrest. The World Press Freedom Index has ranked Eritrea last out of 180 countries for more than a decade, behind China and North Korea. In 2019, the Committee to Protect Journalists designated Eritrea the most censored country in the world.

While we have reason to hope that Isaak is still alive, his present location and condition are unknown. In 2008, there were unconfirmed reports that he was transferred to a maximum security prison where he became seriously ill and was admitted to a hospital in the capital Asmara. Isaak is likely being held in the Eiraeiro prison camp, one of a network of secret prisons where thousands of political prisoners are held in what Amnesty International calls “unimaginably atrocious conditions.”

Isaak’s case offers a looking glass into President Afwerki’s domestic repression, and his government’s systematic and widespread gross human rights violations of its own Constitution. It is also a case study of the global assault on media freedom by authoritarian regimes that have enjoyed an impunity that has intensified under the cover of the pandemic.

There is incontrovertible evidence, as documented by the U.N.’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), of the Afwerki regime’s culture of corruption and criminality, including patterns of enforced disappearances, arbitrary arrest and detention, inhumane prison conditions, and crackdown on dissent.

Last year, the OHCHR confirmed that Eritrean armed forces massacred scores of civilians, including children as young as 13 in the town of Axum in Ethiopia’s Tigray region. More recently, the U.S. Treasury sanctioned Eritrea’s military leader in connection with serious human rights abuses in Tigray.

The culture of impunity has found expression in the Afwerki regime repeatedly ignoring every petition and relevant ruling for Isaak’s release, including a final and binding ruling by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ (ACHPR) in 2016.

European citizenship should provide leverage, but Isaak’s Swedish citizenship has not produced effective action by Sweden, five complaints imploring the Swedish Prosecution Authority (SPA) to open an investigation having been rejected so far. The latest was filed on October 28, 2020 by Isaak’s Swedish lawyers, Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF) and eleven prominent international lawyers.

The SPA has refused to open an investigation on the grounds that, among other reasons, it could have a “negative effect” on Swedish-Eritrean relations and “diminish the possibility” of securing Isaak’s release. Yet, astonishingly enough, the SPA had already made the determination that “there is reason to assume that at least crimes against humanity have been committed against Dawit Isaak.”

The Swedish prosecutors’ ongoing refusal to investigate Isaak’s case appears to have undermined the rule of law, infringed upon the Swedish government’s prosecutorial duties and responsibilities, and may also be said to indulge, if not incentivize, impunity.

Nor is there evidence that diplomacy is working. Across two decades, nine Swedish foreign ministers had been unsuccessful in securing Isaak’s release. The Swedish Parliament early next year is to present the findings of a long-awaited independent parliamentary commission of inquiry set up to review and evaluate the government’s efforts to secure Isaak’s release.

According to an RSF report, rather than hold the Afwerki regime accountable, Sweden lobbied the UN Security Council to lift sanctions against Eritrea, and advised the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency “against providing financial support” to Radio Erena, Eritrea’s only independent radio station, which broadcasts from France. As the report put it, “wary of jeopardizing Dawit Isaak’s freedom, Sweden has essentially been made to dance to Eritrea’s tune.”

When democracies act together, even authoritarian regimes can be shamed into responding. The levers are there, including invoking the Declaration Against Arbitrary Detention in State-to-State Relations (endorsed by 67 states, including the United States and Sweden) and imposing targeted Magnitsky sanctions against the senior Eritrean officials involved in acts of corruption and rights violations against Isaak and his colleagues, a move advocated last month by an international coalition of leading NGOs and human rights organizations, experts, advocates and journalists. Hold U.S. House and Senate hearings underlining the global assault on media freedom. Support the call of UN experts for the urgent release of Isaak. And finally, refer the case to the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, pursuant to the 2016 recommendation of the UN Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Eritrea.

Twenty years is beyond outrageous. Every day that Isaak remains in prison, the authoritarians of the world take another lesson in what they can get away with.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com