In 2019, Jason Henrichs took 46 flights for business, traveling to cities where he stayed at hotels, dined at local restaurants, and sometimes even visited tourist attractions like the Liberty Bell.

In 2020, he took just three flights.

The traveling life has its perks—Henrichs, the CEO of Alloy Labs, a consortium of community banks, has Executive Platinum status on American Airlines, Gold Elite status at Marriott, and membership in not one but three private airport lounges. He has 350,000 miles, which he can use to fly his whole family across the world for free.

But forced to stay at home during the pandemic, Henrichs got a taste of a life where he sees his family more, and is just as effective at work. He’s even been able to convince banking colleagues who have long been averse to giving up in-person meetings to move online. The talks he once flew across the country to deliver to boards of directors are more frequently streamed online now, and so are the meetings that would have lasted in a bank over 2 or 3 days but now are spread out over short Microsoft Teams huddles over 2 or 3 weeks. And lo and behold, he and his colleagues are getting more done.

“This isn’t about just reducing expense. This is about increasing effectiveness,” says Henrichs, who says he’ll likely travel once a month, rather than once a week, after the pandemic.

Tens of thousands of road warriors like Henrichs—and their employers—are coming to a similar conclusion, which is going to cause a reckoning for the already-battered leisure and hospitality sector. U.S. companies’ travel budgets declined by 90% or more in 2020, according to Deloitte Insights. Even if the pandemic ebbs, companies looking to become more environmentally sustainable won’t likely go back to the same volume of travel as before; corporations like Zurich Insurance Group AG, Bain & Company, and S&P Global have announced plans to cut business travel emissions in the next few years, with Zurich aiming to reduce emissions by as much as 70% by next year.

This could mean big losses for airlines, hotels, rental car companies, and other industries catering to corporate travelers. Business travelers make up 12% of airline passengers but 75% of revenues on certain flights. They brought in steady revenue to hotels when they attended conferences and events and then stayed a few extra days to vacation with their families.

Some executives predict that business travel will return to 85% of pre-pandemic levels, says Lindsey Roeschke, managing director for travel and hospitality analysis at Morning Consult. She considers that an optimistic take. “Even if I’m wrong, and we do see a return to those levels,” she says, “that’s still a massive loss for the industry as a whole.”

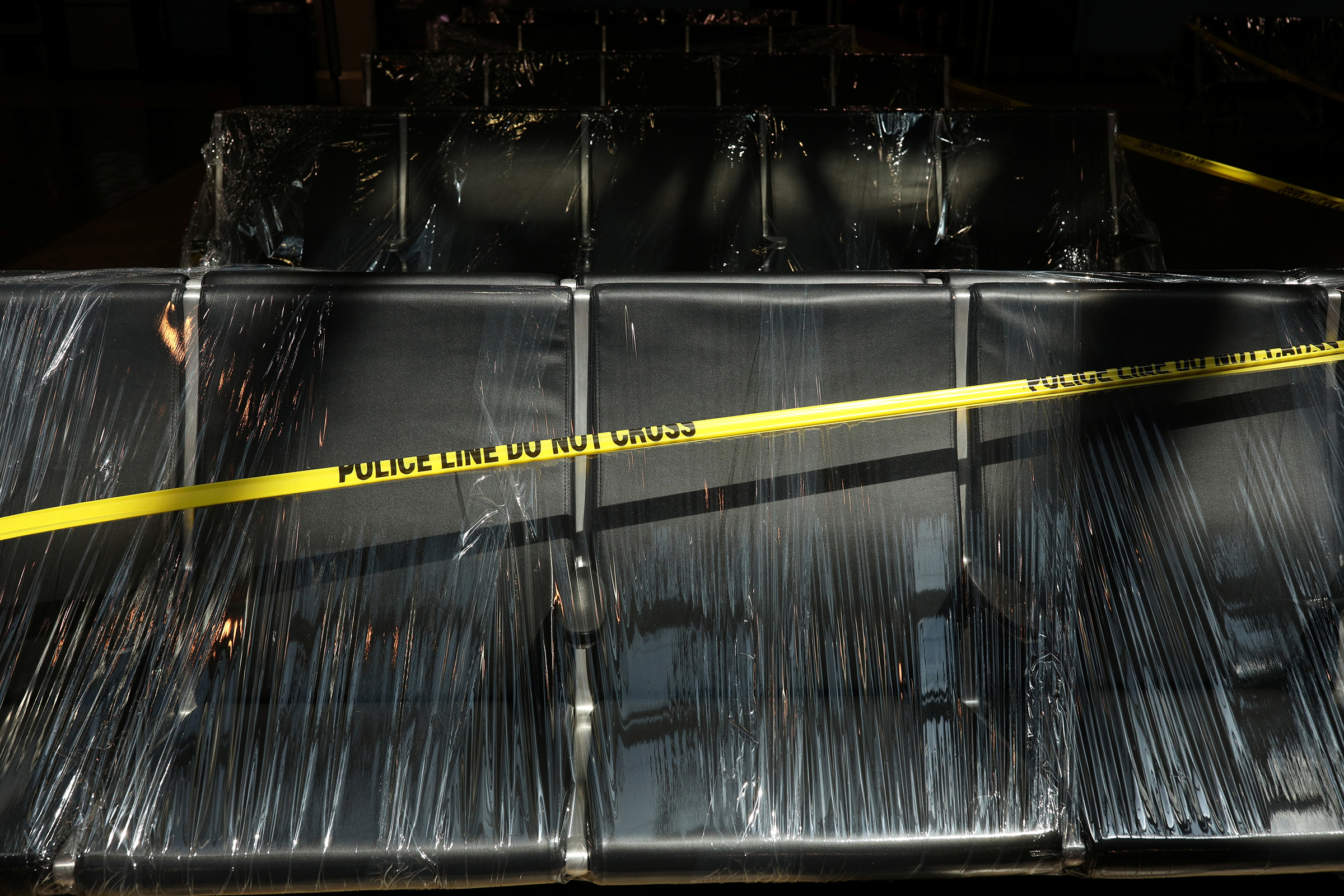

The hospitality industry is feeling it. During the pandemic, rental car companies like Hertz, hotels like the Fairmont in San Jose, and international airlines including Aeromexico, Virgin Atlantic, and LATAM all filed for bankruptcy protection. Government supports that kept the U.S. airline industry afloat ended September 30. The hotel industry is expected to earn $59 billion less in business travel revenue this year compared to 2019, according to the American Hotel and Lobby Association. Airlines are expected to lose $51.8 billion in 2021 alone.

“We’ve been burning cash for 18 months,” says Dave Harvey, vice president of Southwest Business. And now the government support has ended. “We’re all flying naked at this point in the fourth quarter.”

It can be hard to picture those losses in terms of billions of dollars. But it may be easier to picture the ripple effects—businesses closed, workers laid off, airlines canceling flights—of hundreds of thousands of Jason Henrichses traveling less.

The ripple effects of fewer business travelers

One of Henrichs’ favorite business travel destinations was Boston; he and his family lived there years ago, so he still had friends he could grab dinner with after a day of meetings. He’d stay near Back Bay, say, at the Marriott Copley Place, and wake up early to go for a long run by the Charles River before work.

He hasn’t been there since October of 2019.

Some of the places where he used to meet friends are now gone. He’d get dinner at Eastern Standard in Kenmore Square, or oysters at Island Creek, but both are now closed permanently after negotiations broke down between the restaurant owners and the real estate group that owned the properties.

He usually flies American Airlines, but since the pandemic, that airline has dropped some routes and is considering where else to cut. American is facing staffing shortages after furloughing flight attendants and offering buyouts to pilots during the pandemic; it has about 16,000 fewer employees than it did in 2019.

Henrichs stays mostly at Marriott hotels because it’s where he has elite status. Boston’s flagship Marriott, at Copley Place downtown, laid off 230 employees in September. Overall, Marriott hotels in the U.S. and Canada had a 45% occupancy rate for the three months ending June 30, compared to 80% in the same period in 2019, according to earnings reports. At least four Marriotts in New York City have closed permanently since the beginning of the pandemic.

It’s not just big companies that are struggling. Elizabeth Morales was a housekeeper at the Boston Copley Place for 26 years until she was sent home in March 2020 because of the pandemic. The company kept telling her they’d call her back when it got busier, until September of 2020, when it called her and hundreds of others and said their positions had been terminated. “It was really hard for me,” says Morales, 51, who supports her elderly parents. She applied for 30 jobs before she found a new one only a few months ago. Unite Here Local 26 organized a boycott of the Marriott, alleging the hotel is contracting out operations to companies who pay workers less.

Ironically, cuts like this could also make travel less pleasant for everyone when they return to travel. Business travelers subsidized other travelers, to some degree, so as they disappear, airlines are figuring out how to cut costs. They’re cutting routes to cities that people visited primarily for business, routing more flights through hubs, and talking a lot about efficiency. These cost savings also mean fewer available pilots and other flight crew, so weather delays and maintenance issues can trigger a huge chain of delays, as they did last week when Southwest canceled about a quarter of its flights after weather problems in Florida disrupted its network. Other airlines may see similar issues, especially if travel gets busier during the holidays. “We’re concerned about the holiday travel season—they say we’re going to fly more during the winter than we did in the summer, but we’re worried they don’t have the ability to fly that many planes,” says Capt. Dennis Tajer, a spokesman for the Allied Pilots Assn., which represents American Airlines pilots. (American did not return a request for comment, citing the quiet period before the company reports earnings on Oct. 21.)

Henrichs has already noticed the changes. On a recent trip to Harrisburg in August, Henrichs was told on a Friday, after weather delays and mechanical issues had grounded his plane, that the airline couldn’t get him home until Tuesday. (American cut a number of flights this summer because of weather, mechanical issues, and staffing shortages.) Rather than wait around, he rented a car and drove to Philadelphia, where he hoped to get on a plane the next day, only to find that Marriott’s website had crashed and the hotel where he thought he’d made a reservation was actually sold out. He went door to door until he found a vacancy at the Homeaway Suites, but by then it was 11 p.m. and there were no nearby restaurants open, so his dinner was a Bud Light and a bag of chips. He got home the next day. “The system has become less resilient,” he says.

Some companies still think business travel will return

Some hospitality companies contest the idea that business travel won’t come back. “We are optimistic that we’ve turned a corner,” Anthony Capuano, Marriott’s CEO, said on an August earnings call, although special corporate bookings were down 45% compared to the same period in 2019. On a recent earnings call, Delta said it expected business travel to be back to 60% volume by the end of this year, and potentially 80-100% by the following year.

Southwest Airlines has actually doubled down on business travel during the pandemic, adding 18 airports, dozens of sales staff, and making it easier for corporations to book flights through their own travel systems

“There’s a pent up demand for face-to-face business meetings, conferences, events, networking—people are just starved for that,” says Harvey, of Southwest Business. Southwest is hoping to capture those travelers by attracting companies who want to pay lower fares but still want to travel, he says. He also argues that since companies have more remote employees now, there’s a new class of business travelers who have to fly to headquarters a few times a year.

But even people who have spent decades on the road say that the pandemic has made them realize that technology has finally made it feasible to have good communication without traveling. Tina Perkins, who has worked for Epic Systems, a Madison, Wisc.-based electronic medical records company, for 20 years, says she loved traveling to a new city once or twice a month to help hospitals implement Epic software. But “I have been sort of shocked at how we have been able to adapt,” she says. “We are as effective in this hybrid world, which was surprising having done some things one way for such a long period of time.” She says she’ll likely travel once every 4-6 weeks going forward, rather than once every 2-4 weeks. Other Epic travelers have made the switch too; employees now take, in total, about 1,000 trips a month, down from 3,500 before the pandemic.

The hotels and airlines that figure out how to make their model work without business travelers are going to be in the best position going forward, says Anthony Jackson, the U.S. Airlines Subsector leader at Deloitte. During the last recession, airlines expanded their premium economy seats to attract economy travelers who were willing to pay for an upgrade but not first class, and cost-conscious business travelers. Now, airlines will likely further expand premium economy, in part to give travelers still worried about COVID-19 a way to pay for more elbow room, says Alan Lewis, managing director for L.E.K. Consulting. Delta said October 13 that it actually made a profit in the three months that ended Sept 30, and that premium cabin seats drove much of that recovery. Business travel is still less than 50% recovered, the company said.

Like airlines, hotels are going to have to think up new ways to attract traveler money, says Roeschke, of Morning Consult. They might decide to try and lure digital nomads who don’t have to pay rent anymore and are traveling around the country as they work. Or they may offer “bleisure” – business leisure – packages to people who want to work and vacation all in one trip.

That may attract travelers like Henrichs, who still has to make some work trips. On his last business trip before the pandemic, Henrichs attended a weeklong conference of the American Banking Association in Orlando. Since his in-laws live near-by, he used miles to fly his wife and kids down to Orlando, too. They rented an Airbnb near the conference, and he commuted back and forth via Lyft. Still, the American Banking Assn. is holding the same conference this year in Tampa, but neither Henrichs nor his family are attending.

There is a silver lining to Henrichs traveling less frequently though; he says he’s spending more locally. He and his family are going out to local restaurants and checking out neighborhoods and businesses he would have been too burned out to try back in the days when he was always on the road. He hopes this will lead to a resurgence of stores on Main Street, the type of places that business travelers might not have deigned to visit.

“Normally, I travel so much that by the time I get home, I want to eat at home,” he says. “Now, I’m home plenty. So eating out can be fun again.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com