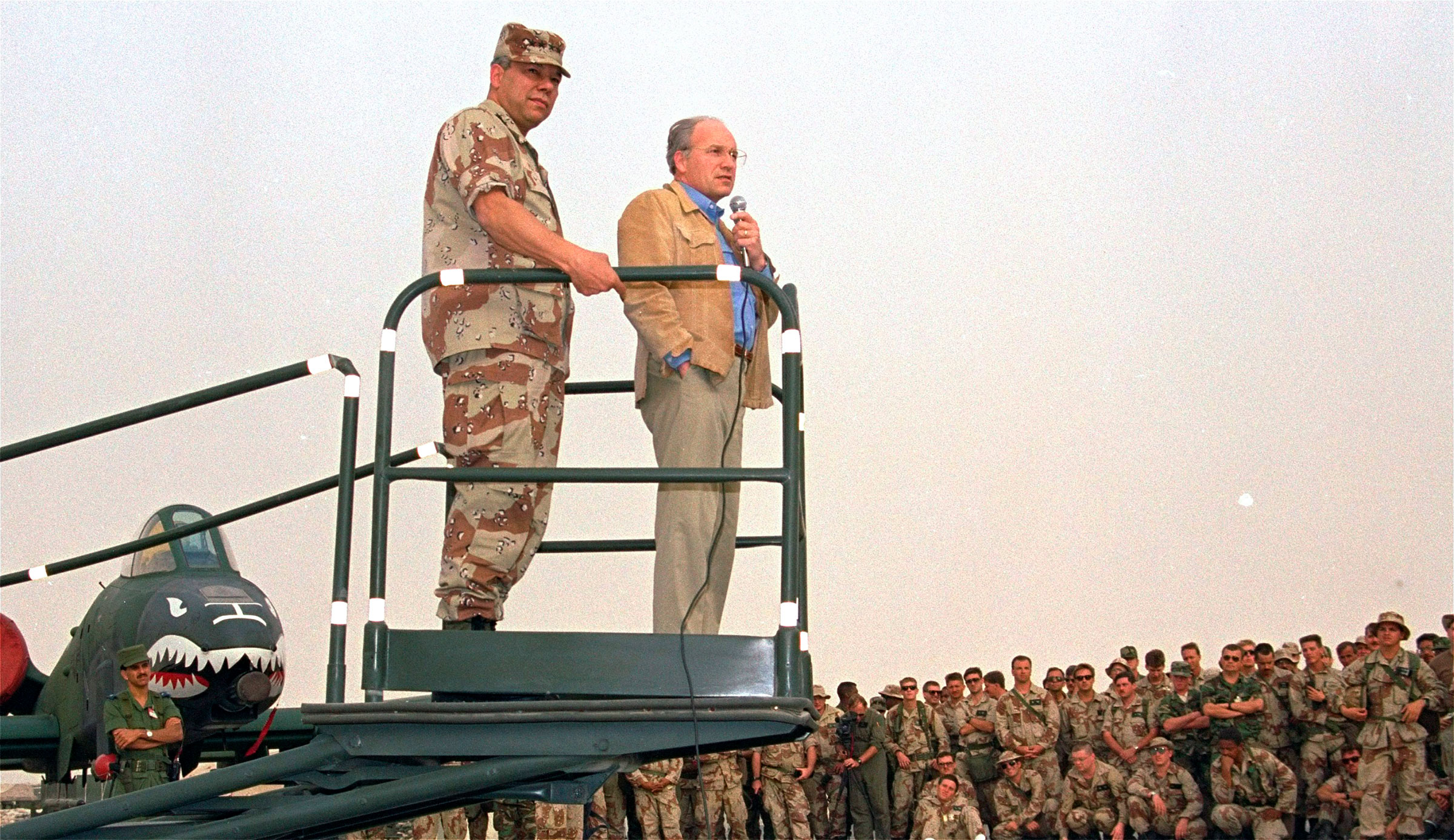

General Collin Powell died on October 18. His legacy, as Philip Elliott writes, was complicated, and the General knew it. TIME interviewed Powell in 2012, on the occasion of the publication of his book on leadership It Worked For Me: In Life and Leadership. The interview was edited and condensed at the time, but to mark his passing, we are publishing a fuller version that illustrates in more detail how he felt about the huge events of his life.

In It Worked for Me you write that the two months that you spent mulling a run for president were the most difficult of your life. Why?

I never had had any political aspirations. I’m a career soldier; I never really belonged to a political party. I had views about things but I never spoke about them. Even when I worked for President Reagan, I was an active-duty officer and I had to be careful of what I did and I did not do. But then I leave the army and suddenly my [first] book comes out and there’s this enormous interest in my running for office and so I had to think about it.

It was something of a guilt trip that I felt on top of me. People said, ‘You have to do this,’ and I felt obliged. A soldier always wants to do what he’s supposed to do. It was a very difficult time as I worked my way through this and I kept running into obstacles that said to me, ‘Are you sure? Are you sure?’ After spending that time and frankly losing weight—it was really tough—it became very clear because there was not a single morning that I woke up and I put my feet on the floor and said, ‘This is right for me. This is what I want to do.’

I didn’t want to do it, and my family didn’t want me to do it. I said I’ll find other ways to serve the country and there are many people who do want to campaign and run for political office. It’s not for me. I think you might detect from the book that I try to learn all I can about an issue but then at the end of the day I have to go with my instinct, what I think is right, and I think that was right. I’ve been asked many times since, ‘Do you have any regrets?’—I’ve been asked for the last 17 years, and the answer is no. No regrets, because I continue to find other ways to serve the country.

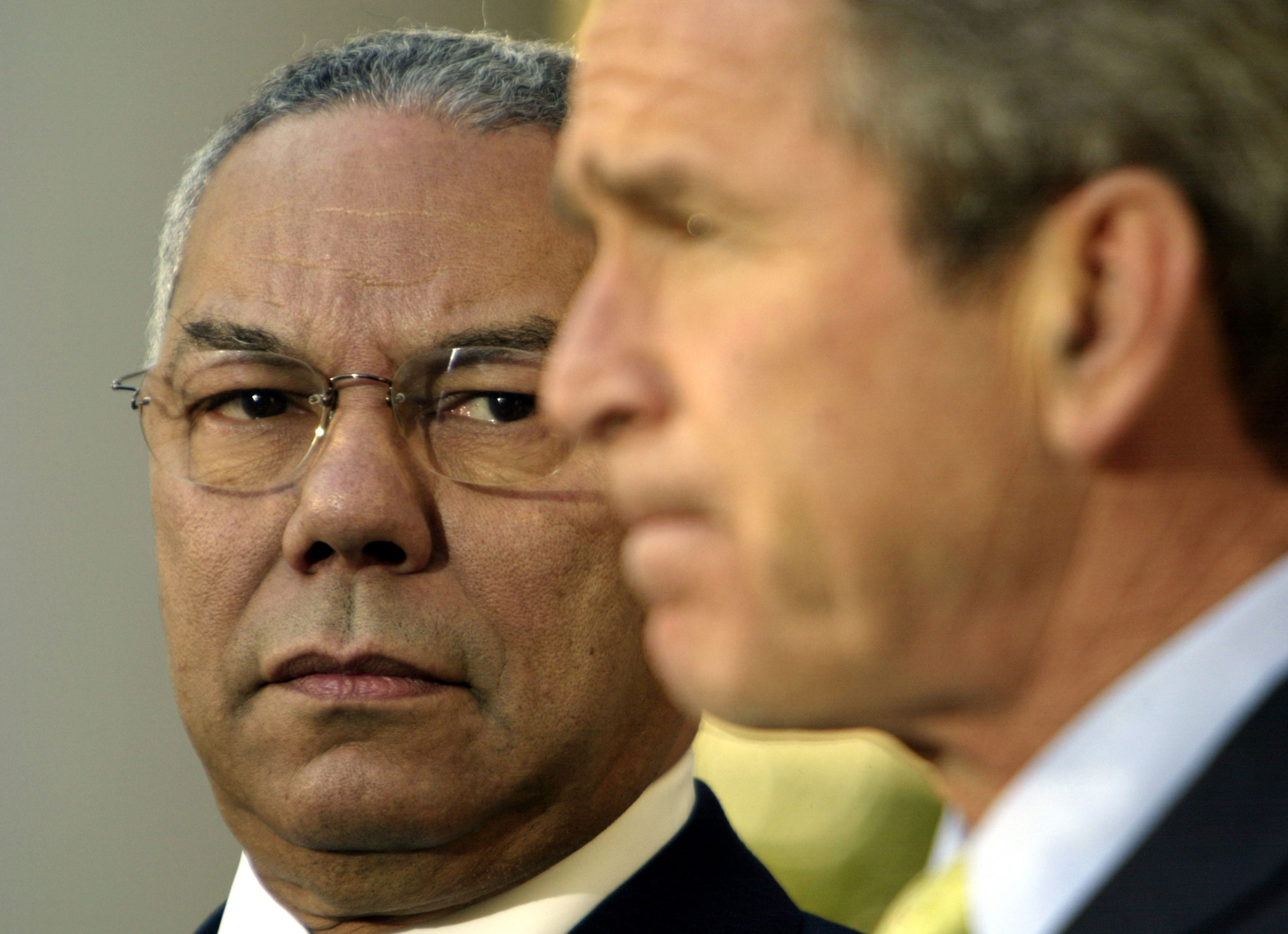

In Chapter 2 of your book you talk about doing hard jobs and seeing them through, and the end of your term as Secretary of State. Do you think you timed that quite right? Do you wish you had gone sooner or do you wish, knowing what happened later, that you left it a little bit longer?

Excellent question. I always had planned to stay one term. I was getting on in years and I wasn’t looking for an eight-year job. And President Bush pretty much understood that. So when we got into the beginning of the last year, early 2004, I reflected with the President on what had been going on, and there were tensions within the team, as have been well documented. And I said to the President I thought it was best that I leave as planned at the end of the fourth year and he thought yes, that is a good idea. And so there was agreement, no-unpleasantness agreement. I think he should have perhaps made more radical changes within his Cabinet, but he chose not to, and I left.

You also talk about how you think members of Congress stay on a little longer than they should.

We need congressional experience. We need people who know how the system runs, but it seems to me that it really is not necessary to stay there for an entire career. This really wasn’t what the Founding Fathers had in mind, for you to stay there for your entire life, although it’s not a new pattern. It’s happened in the past. I think after awhile you become so embedded, so satisfied with the way things work here that you might lose your edge. It’s like we do in the Army: move on, and let some new people come in and come up and make the way clear. It’s harder and harder to get new people to come in if the positions that they would want to come in for are frozen because of incumbency. In the military, they make you get out. There’s a story in the book you may have tripped over. When I was made a three-star general, at the same time that I was congratulated, I was told ‘Two years from now to the day, if we haven’t given you another job or promoted you, we expect your resignation, your retirement papers, on our desk.’ That’s not bad. Make room for young people coming up.

Do you still consider yourself a Republican?

I consider myself a Republican. I live in a state where you really don’t have to register, but I’ve always been inclined towards Republican views on foreign policy, Republican views toward national security. I am fairly moderate on social issues, more moderate than the party has become in recent years. And so people would say, ‘Well, is he really a Republican or is he just sort of a RINO, a Republican-in-name-only?’ They can speculate all they want. What I am is an American citizen who tries to make the best judgments about the issues and not just be trapped in a political ideology that has an identity to it as a Republican or a Democrat.

You are Episcopalian. In the Old Testament, God tells King David that he cannot build the temple because “Thou has been a man of war and has shed blood.” Do you feel that having been a man of war has cut you off from—I’m not talking about job opportunities—but other opportunities? Would there have been a different Colin Powell if you had not gone into the ROTC?

See, I would characterize myself as a man of peace, who, when it becomes necessary to fight war, knows how to fight a war, and has a pretty good sense of how you are successful in a war. I had a debate with a former archbishop of Canterbury in early 2003, just before that war began in Iraq, and he asked me, ‘Why don’t we use soft power? Why do we always have to go to war? Why do we always use hard power?’ My answer to him was, ‘I agree with you. I always prefer soft power. I’m known as a reluctant warrior. But you know it wasn’t soft power that got rid of Hitler. It wasn’t soft power that saved the United Kingdom. It isn’t soft power that got rid of the Japanese imperial army and stopped that war finally.’

So I’m all for soft power, but it isn’t always the answer. America has always been a nation that seeks peace, seeks diplomatic ways to solve a problem. But when war becomes necessary we’re going to do it and we’re going to do it as best we can and as quickly as we can and do it right. America is unique in that every time we have gone to war, when the war is over, we tend to build up the nations we defeated. We did that with Germany. We did that with Japan. And then my last sentence to the archbishop was, ‘You know, the only thing America’s ever asked for, particularly after World War II, was no land, no empire, just give us enough land to bury our dead. That’s all we ask for.’ I’m not sure he was satisfied with the answer.

You write in Chapter 35 that the date February 5, 2003, is burned on your brain as much as your birthday. It’s the day that you presented the case for war to the United Nations. If it had not been for you, do you think we would have gone to war?

You have to remember that three months before I made my presentation to the U.N., the Congress had overwhelmingly passed a resolution based on the same intelligence information that said to the President, if you feel it necessary to do this, then we support your going to war. And so the predicate had already been laid by the Congress. By the time Feb. 5 came around, the President in his own mind had already decided that the only way we can dissolve this problem is not through diplomacy but through military action.

And so my presentation was to present the case for military action. If something didn’t happen in the next few weeks, then the President was going to take military action. It was pretty clear by then that Saddam Hussein was not going to comply and he was not going to make full disclosure of what he had. So we were on a path to war then, and it was my task as Secretary, properly, to present to the United Nations the reasons that we saw it was going to be necessary to go to war.

Do you find a lot of people say that they were uncertain about the war until they heard you, because of who you are?

A lot of people said that. And that was the purpose of the presentation. It was to give a case to the American people and to the international community of what we believed to be the reality on the ground—that there were weapons of mass destruction. And everything I said could have just as easily been said by the President, and many of the things I said he had said earlier in the State of the Union address. These were things that were being said by our commanders, by the Secretary of Defense, by the Vice President, and by the National Security Advisor, because we all believed there were weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.

Everybody remembers my presentation because it was so vivid. They forget that the basis for my presentation was a national intelligence estimate that had been given to the Congress months earlier before they voted on the resolution for the President.

You write in your book that you were dismayed then to see so many in the intelligence community backpedaling from that national intelligence estimate reasonably soon afterwards.

Well, I was quite surprised when it started to fall apart. You know, ‘Well, there aren’t three sources; it’s really one source.’ What? And then suddenly a number of members in the intelligence community at fairly senior levels started writing books saying, ‘Well we knew [the source of the intelligence] was flaky.’ You did? What a minute. His flakiness was in the President’s State of the Union address. The President talked about weapons of mass destruction and biological events. So where were you? And then suddenly they start saying ‘Well we tried to tell the senior levels but it didn’t get through.’ Well, you didn’t try very hard. There were people who knew that the source was flaky and they didn’t step forward. That was annoying.

So even though people remember you as the guy who made the case for war, you are not personally responsible for the fact that America went to war on grounds that are false?

With respect to the weapons of mass destruction, not totally. I mean this was a man who had them in the past, had used them in the past, and had the capability to develop and use them again. The error was we thought he had them, and he did not. And while I was making the case on Feb. 5, that case was being made by members of Congress, by the President, by all the Cabinet members, by our military commanders, but mine is of course the most vivid presentation of the case.

Is it because of who you were, because you were always such a reluctant warrior that people thought, ‘Well if Colin Powell says it…’?

Yeah. I acknowledge that openly.

Even though it is not your personal responsibility, do you feel guilt over the war, the lives that were lost in this fruitless search for weapons of mass destruction?

I feel bad about any loss of life on either side of the conflict, but it was a case where the intelligence information we were getting made it quite clear at the time. The CIA stuck with that assessment long after we didn’t find anything. They still believe that their judgments at the time were correct. We based our case on those judgments and what we were hearing from others. Then the President made the decision and I think at the time it was a justified decision based on what we knew. How the war was fought and whether it was fought correctly is another issue entirely.

One of the great images in your book is this image of you leaving your command and you angle the mirrors on the car in a certain way so that you don’t, I think you say see your ideas being put in the garbage bin…

That’s why you turn the radio up loud, and roll up the windows.

How do you angle the mirrors on that day, on Feb.5, 2003?

I’ve been asked about it almost every day for the last nine years. I get asked about it almost every day, almost every speech, and what I say is I made the best presentation that I could make, which was expected of me and which was my job, of the intelligence we had. The intelligence turned out to be wrong, and there are a lot of people that can be examined as to why it was wrong, how did it get in the President’s speech, why was everybody using it, why were members of Congress standing up in the Congress and making the same case that I subsequently made, why did Congress vote for a resolution?

That’s all interesting, but has nothing to do with the burden that I carry. I did it, as I say in the book, and I had to move on. I was still Secretary of State. I couldn’t go in a corner and go fetal. I had to carry on. And my pattern throughout my life is when things go not quite the way you want it, you have to learn from the experience and then move on. And that’s what I mean by that little story of when you give up command, it’s over for you. You’ve got to move on. Always be looking through the front windshield. Reflect on what’s behind you, but always be looking ahead or you can trap inside yourself in a bubble that is destructive.

Some neo-conservatives have taken credit for the Arab Spring, people from your era, saying that the example of democracy in Iraq and Afghanistan started the ball rolling for the rest of that area. Do you agree with that assessment?

I think that is probably one of the factors, but I think the real factors were disappointment finally, on the citizens of the nations of the Arab Spring. They’re watching television, they’re online. They’re seeing that there’s a different world out there and they’re wondering, ‘How come we can’t pick our leaders? Why don’t we have an economy that’s functioning? Why do we have leadership that’s corrupt?’

Remember how it all started, with a street vendor in Tunis who just wanted to get permission to sell his wares, his fruit, his vegetables. And he couldn’t get it. He was fed up with government, fed up with the corruption. And he self-immolated, and killed himself. So the most driving force I think for the Arab Spring was the desire for jobs, a better life, non-corrupt governments and representative governments. And as they were looking around, looking at Eastern Europe that came out from behind the Iron Curtain, looking at China that came out from the Cultural Revolution, looking at Latin America, where all those nations got rid of their generals, and they simply said, ‘It’s our turn.’

I always trace it back to the Helsinki Final Act of 1975 that Jerry Ford signed with many other nations that essentially said people should have the right of self determination… That they should pick their own leaders. And I think that was the spark that lit the fuse that brought the Soviet Union to an end, that brought the Warsaw Pact to an end that freed Europe and continued moving. And finally the spark hit the tinderbox down in the Arab world.

You say that you were in Peru on 9/11, and you were in Asia when some of the key decisions were made about CIA black sites. And you urge Secretaries of State to stay home a little more. Do you think the Secretaries who followed you traveled too much?

No. I didn’t say that. I said you have to make your own decision as to what proper travel is. I was taking issue with some of the folks who like to criticize me cause I didn’t travel enough. I think you have to balance where you should be, and on a number of occasions while I was secretary I found that I wish I was home while this was going on.

Now Secretary Rice and Secretary Clinton traveled a lot more and they found that to be the best use for their time. So I was just making a case that you really should look carefully at how you use your time and whether you’re using it in the best possible way, and I thought I was trying to use mine in the best possibly way, and the two distinguished secretaries that followed me will certainly use theirs in the best possibly way as far as they’re concerned. I was not so much criticizing as I was making the point, where you are on the battlefield is important and you should always be where you can influence the action and where you can be at the decisive place at the decisive time.

Do you think things would have different had you been in America on 9/11?

It wouldn’t have been any different on 9/11. I was blessed to have a good staff and a deputy who was jumping into action while I was flying home.

What about black sites?

There were some things that took place with respect to interrogation policies and detention policies that didn’t get full discussion and maybe would have had that full discussion had I been here and could have pushed it or participated in it.

Yesterday John Brennan, who is the administration’s counterterrorism advisor, spoke publicly about the President’s use of drones for the first time, and I guess that is a sign that the administration is trying to make covert operations a little more overt. Is that something that you are in favor of as a policy?

I’m in favor of what Mr. Brennan said yesterday, in that we know there are enemies out there. They’re hiding. They are not a state enemy that is easily identifiable as in other wars, but it is a war. And if we have the capacity to identify these people and are sure we know the target and what danger that target presents to us, then as Mr. Brennan said, it is within the law for us to go after these individuals before they go after us, whether it’s covert or overt.

So you don’t have a particular view on whether or not covert operations are in America’s interest as a policy?

Well, covert operations is a very large term, and you may recall I was National Security Advisor and Chairman and I was deeply involved in many, many covert operations as part of my job. And sometimes covert—the drones don’t seem to be that covert anymore. There are other operations that are very, very covert, meaning that they take special authority from the President and generally you don’t hear about them.

In your book you explain how you evaluate people for leadership. You have this sort of 50/50 rule, 50% on what they’ve done and 50% on how you feel they’ll perform in the future. Do you sometimes wonder, have you ever given thought on why it is you got to the top?

I worked like a dog for most of my life. I’ve always tried to do my best, and the army invested a lot of time in my education: war colleges, graduate school to get an MBA. They made quite an investment in me hoping that that would improve my performance and increase my potential. But as to why I got a particular job or a particular person to take an interest in me, you’ll have to ask that person. But you know a lot of the things that happened to me were quite surprising. I didn’t think I was about to become Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff until Mr. Cheney called me out of a conference to talk to me about it, and it happened. So I’ve always tried to just do my best in every job and I hope that comes through clearly in the book and things will happen or they won’t happen. I’m not owed anything by the army or the government.

Do you never try to turn the chessboard around to see what was it that people were seeing on that side?

No, that’s looking in the rearview mirror. I just say look, I’m doing my best. If my best is enough to move me up? Fine. But I know a lot of guys, friends of mine, close friends, who are also doing their very, very best, and they were just as good as me, but the opportunities didn’t present themselves to them, and those opportunities presented themselves to me. And so I have been very, very fortunate. A lot of it is luck. A lot of it is people seeing things in me. And the majority of it, I think, is I work hard. One line I have is that I came into the army to be a soldier, not a general, and any time they had told me, “You’ve been a soldier for long enough. You can go home now,” I would have gone home happy. I found satisfaction throughout my army career and I didn’t need promotions to give me the satisfaction of being a soldier.

Do you ever use Sir Colin?

Only in the United Kingdom. It wouldn’t be considered appropriate here, and my British friends would not consider it appropriate for me to use it here. It’s honorific, and when I received my knighthood from Her Majesty it was done in a very low-key manner in her private office, only three of us were in the room, myself, my wife and Her Majesty. And she simply came across the room and picked up the beautiful box and, “Sir Powell, Mrs. Powell, good to see you again. Here, thank you for everything.” And we sat down and had a nice conversation and that was it. So I’m very, very proud of it. My parents were no longer with us at that point. They were British subjects, very proud British subjects.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com