Thousands of workers have gone on strike across the country, showing their growing power in a tightening economy. The leverage U.S. employees have over the people signing their paychecks was amplified in Friday’s jobs report, which showed that employers added workers at a much slower-than-expected pace in September. The unemployment rate fell 0.4 percentage points during the month, to 4.8 percent, the government said Friday, and wages are continuing to tick up across industries as employers become more desperate to hire and retain workers. In the first five days of October alone, there were 10 strikes in the U.S., including workers at Kellogg plants in Nebraska, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee; school bus drivers in Annapolis, Md.; and janitors at the Denver airport. That doesn’t include the nearly 60,000 union members in film and television production who nearly unanimously voted to grant their union’s president the authority to call a strike.

Jess Deyo is one of nearly 700 nurses who have been on strike as part of the longest healthcare strike in Massachusetts history. For the past seven months, Deyo has reported for duty at the hospital in Worcester, Mass. where she worked as a nurse for more than 15 years, sometimes bringing her daughters, and standing outside through the chills of spring and the heat of summer. The nurses are demanding higher nurse-to-patient ratios after a harrowing 19 months of working during a pandemic. “There’s no choice to give up on the strike,” she says. “It’s bigger than us—it’s for everyone.”

Most of these strikes aren’t counted by the federal government, which in the 1980s started only tracking strikes that involved 1,000 or more workers and that lasted one full shift or longer. There have only been 11 of those so far this year, according to government data, at places like Volvo Trucks and Nabisco.

But academics at Cornell University launched a strike database on May 1 that uses social media and Google alerts to keep track of all the strikes and protests happening in the U.S., even if they involve just a few workers. The database shows a picture of growing worker activism, of small actions that tell a story of how people at workplaces small and large are feeling after 19 months of a global pandemic, says Johnnie Kallas, a PhD student who is the director of Cornell’s Labor Action Tracker. It has documented 169 strikes so far in 2021. “Workers are fed up with low pay and understaffing, and they have more labor market leverage with employers needing to hire right now,” he says. “You are seeing a little bit more labor unrest.”

Read More: Hourly Workers Are Demanding Better Pay and Benefits—and Getting Them

Of course, compared to half a century ago, there still aren’t many strikes in the U.S. There were 5,716 strikes in 1971 alone, according to government data from when the government tracked smaller strikes. And the share of unionized workers in the U.S. is near an all-time low, with just 12.1% of workers represented by unions last year.

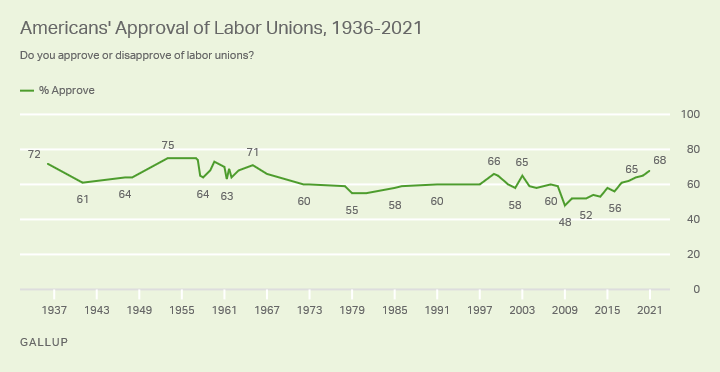

But the activism comes at a time when approval of labor unions—even among Republicans—is trending upwards—and when a low unemployment rate is giving leverage to workers who have long put up with poor conditions and pay. A Gallup poll released in the beginning of July showed that 68% of Americans approve of labor unions, higher than it had been in years and up significantly from the 48% approval in 2009 during the throes of the Great Recession. The poll also showed that 47% of Republicans said they approved of unions—the highest share since 2003—and that 90% of Democrats did.

Greater income inequality, more strikes

Part of the support of unions and organizing may come from Americans’ discontent with growing inequality, much as inequality a century ago galvanized a labor movement then, says Tom Kochan, a professor of work and employment research at MIT. There are a growing number of billionaires in America–708 as of August—with a net worth of $4.7 trillion as of August 17. That’s more than the total net worth of the bottom 50% of Americans.

“I think the accumulated effects of the loss of good jobs in manufacturing, stagnant wages, growing inequality, and the growing disparity between executives and managers and the workforce—all of that is fueling increases in organizing,” he says.

Some of this labor activism was happening before the pandemic, Kochan says, when even the government’s strike tracker showed an uptick in unrest. Teachers in states like Arizona and Oklahoma started striking in 2018 because of low pay and a lack of public funding. In 2020, NBA athletes walked out of a playoff game to protest the shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisc.

The year 2019 saw 25 work stoppages involving 1,000 or more workers, the most since 2001. In 2017, 48% of non-unionized workers said they would vote to join a union if given the chance, higher than the share who said that in 1995 (32%) and 1977 (33%), according to Kochan’s research.

The pandemic worsened working conditions for thousands of workers like Deyo. Kellogg workers at a plant in Battle Creek, Mich., told the local news that they were lauded as heroes for working 16 hour days, seven days a week during the pandemic, and rather than reward them, the company recently decided to offshore some of their jobs. They went on strike on Oct. 5. Musicians at the San Antonio Symphony say they voluntarily accepted an 80% pay cut last season, and that the symphony then proposed first to permanently cut their pay by 50% and then to cut the number of full-time members from 72 to 42. They went on strike on Sept. 27.

Do strikes work?

For their part, employers say that they’re being fair, and that workers are being unreasonable. Kellogg provides workers with benefits and compensation that are among the industry’s best, a company spokesman, Kris Bahner, said in a statement. The company says it has not proposed moving any jobs from the Ready to Eat Cereal plants, which are the plants where the workers are striking, as part of negotiations.

The San Antonio Symphony said, in a statement, that the union and the symphony agreed to a 25% reduction in weekly salary for the 2020-2021 season, but that because there were fewer performances and because fewer musicians could fit on stage because of social distancing guidelines, some musicians did make 80% less than they would have made in a normal season. The symphony needs to make “fundamental changes,” a spokesperson said, and it cannot afford to spend more than it makes through ticket sales and donations.

Carolyn Jackson, the CEO of St. Vincent’s, where Deyo and hundreds of other nurses are striking, says that the nurses are trying to push a 1:4 nurse to patient ratio that Massachusetts voters rejected by a large margin in 2018. The hospital has done research and decided its staffing is appropriate, and that its staffing ratios are in fact better than most other hospitals in the state, she says. Ryan says the hospital announced it was hiring 100 permanent replacement nurses in May during a COVID-19 surge, and that the striking nurses are insisting on getting their old positions back.

That the hospital is not budging speaks to the fact that despite this increase in worker activism, workers may not gain much more power in the long run. Over the last 40 years, the government has made it much more difficult for workers to both form unions and to strike, says Heidi Shierholz, the president of the Economic Policy Institute, a progressive think tank. Amazon was able to effectively interfere in a union vote among its workers this spring, she says, preventing the union from succeeding.

Of course, a hearing officer at the National Labor Relations Board has recommended that the board throw out the results of the Amazon election and do it over, which speaks to a resurgence of government support for labor. President Joe Biden said he wanted to be “the most pro-union President leading the most pro-union administration in American history.” Labor has support at the state and local levels too: California Gov. Gavin Newsom recently signed a packet of pro-worker bills, including one that prohibits companies from imposing quotas on warehouse workers that prevent them from following health and safety law, and another that prohibits employers from paying workers with disabilities less than the state’s minimum wage. And in January, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio signed a bill that forbids fast food restaurants from firing workers unless the employer has just cause, making New York City the first jurisdiction in the country that essentially ended at-will employment.

But even that support may not be enough to force a widespread change of working conditions in an economy where employees haven’t had much leverage since before the Great Recession, or earlier. Even some of the recent strikes haven’t led to workers’ desired outcomes. A five-week Nabisco strike recently ended with many of workers’ demands met, for instance, but the company still won the ability to pay weekend workers less than they do currently.

As for Jess Deyo and the Worcester nurses, many have been forced to move on. After Deyo’s unemployment benefits ended and her health insurance premiums spiked, she decided she needed to find another job so that she could support her family. She’s a single mother. She found a job working as a nurse at a doctor’s office, where she says she feels more appreciated than she’s ever felt at work. The hours are better and she finally feels respected. But she makes $13 less an hour.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com