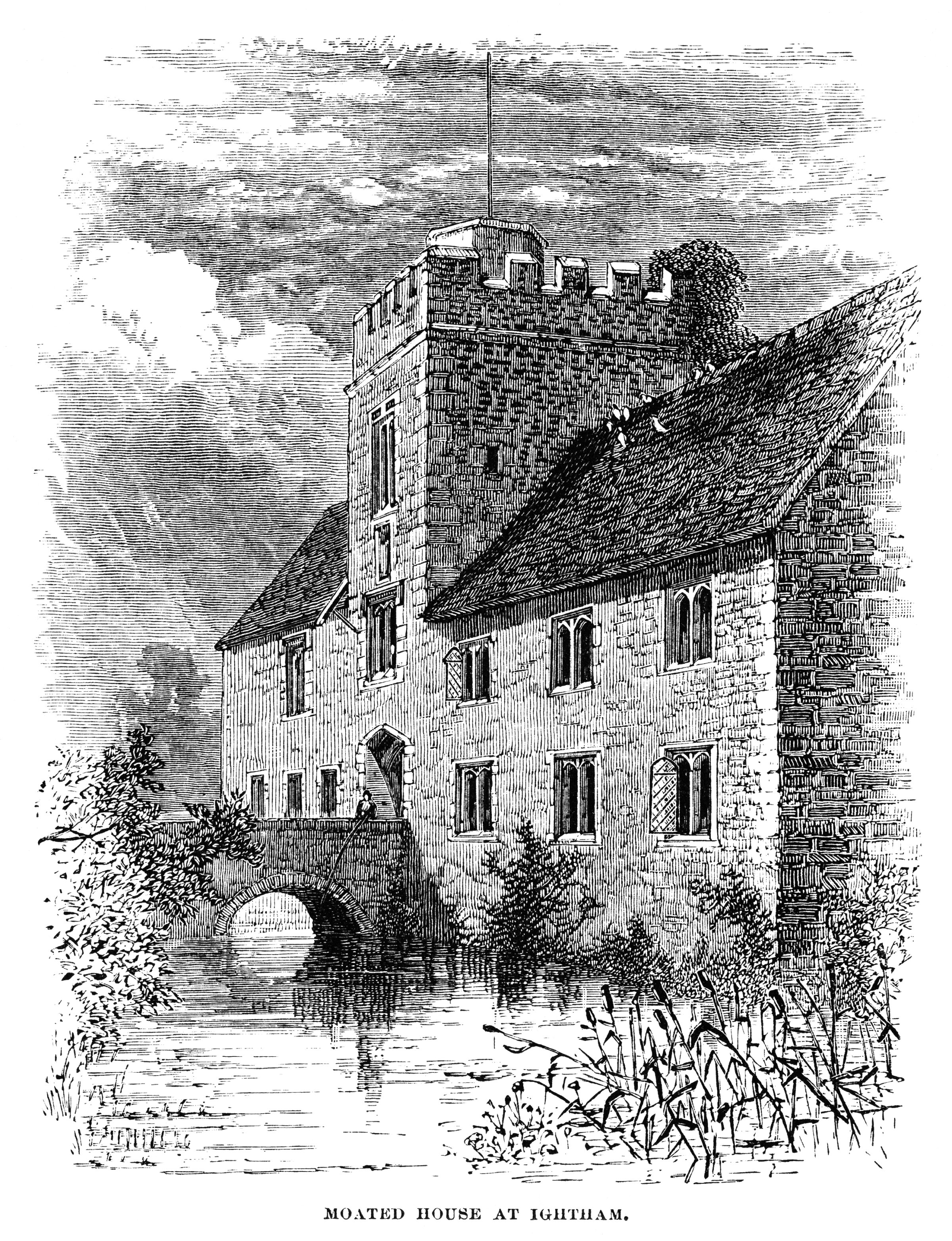

It could have been a screenplay for one of those gentle comedies that British film studios used to do so well: In 1924, a young American from Portland, Maine, was on vacation in England and strolling down the Strand when a colored engraving in a shop window caught his eye. It showed a glimpse into the courtyard of a romantic fourteenth-century manor house, Ightham Mote in Kent. Something about it intrigued him.

Some years later the same young man, whose name was Charles Henry Robinson, was holidaying in England again when he recognized a photograph of that courtyard in a copy of Country Life magazine. Ightham’s owner, Sir Thomas Colyer-Fergusson, was then opening the house to the public on Friday afternoons at a shilling a head; with time on his hands, Robinson decided to go down and see if the reality measured up to the romance.

It did.

Ightham Mote was the stuff of fairy tales. Robinson was enchanted, haunted by its charm. It was, he told himself, “the only house in England that I should ever care to own.” And he was rich enough to buy it. But Sir Thomas, who was of an antiquarian turn of mind—his favorite pastime was transcribing parish registers—had no intention of selling.

Fast forward to the 1950s. Sir Thomas was dead and his heir had moved quickly to sell the estate. Most of Ightham’s contents went in a three-day sale in October 1951, but the house itself failed to make its reserve price at auction. In a last-ditch attempt to save it, three local businessmen formed a syndicate to buy Ightham and thirty-seven acres, paying around £5,500 (approximately $15,400—or just over $162,000 by today’s currency standards) for the freehold with the intention of keeping it safe until a suitable buyer could be found. But there was no sign of a savior. Unoccupied, the house began to deteriorate.

But Robinson hadn’t forgotten his pre-war visit to Ightham; in the spring of 1953, on another of his regular trips to England, he went down to see what had become of the place—and he was appalled at what he saw. “Sinister and cynical, crumbling into its moat,” he wrote later. “It was like some old person, abandoned and embittered, that needed a little affection, care and security.” So he met with the members of the syndicate and suggested he might buy it himself.

What would he do with it? Robinson was a bachelor in his early fifties, and his business interests lay in America. It would cost a small fortune to put Ightham right, and he would have to do it from across the Atlantic. Sailing home on the Queen Mary a week later he had second thoughts, and wrote from the ship to tell the syndicate the deal was off. But when he went to post his letter, the Queen Mary was already approaching New York and its library, which also served as its post office, was locked. The letter was never sent.

Instead, Robinson talked things over with relatives when he got home—they all urged him to buy the house. “I would like to see you spend some money,” said one nephew, “because you know if we kids get it we’ll spend it anyway.” So Robinson bought Ightham Mote and saved it. When he retired he moved in, declaring that “a house like the Mote belongs to the ages. One does not possess it, rather the opposite: one acts as a temporary protector or guardian.”

Robinson’s involvement with Ightham Mote stemmed from two time-honored traditions which have been pursued by prosperous white Americans for years: stately home tourism and a desire to acquire a piece of the Old Country. The story of British nobility and its undignified scramble to marry American money has become part of the folklore of Edwardian landed society. But mid-Atlantic romance continued long after bartered brides turned into cultural clichés.

Americans have always come to Britain as sightseers, marveling at its culture and complaining about its cuisine. The British, meanwhile, patronized their American guests, stereotyping them and constantly reminding them that theirs was an inferior culture. But Britain needed tourism dollars. And the nascent stately home industry was eager to cash in, relentlessly courting Americans and directing its marketing efforts towards America.

In postwar Britain the most famous Anglo-American love affair remained the marriage of the Duke of Windsor and Wallis Simpson. But a glance through the 1947 edition of Debrett’s, the annual directory of peers, baronets and knights, shows that of the then-901 Lords Temporal (hereditary peers in the U.K. Parliament’s House of Lords), forty-five—or almost one in twenty—were married to or had been married to American citizens. In fact, one or two had been wedded to several: the 8th Earl of Carrick, having married Marion Caher Donoghue of Philadelphia in 1930, married Margaret Power of Montana eight years later; at that same time Donoghue became the wife of the 4th Lord Chesham. Helen Zimmerman of Cincinnati, who was a duchess for more than thirty years through her marriage to the 9th Duke of Manchester, exchanged that title for another when she became Countess of Kintore in 1937, giving up her first husband’s three country houses for her second husband’s ancestral seat in the far north of Scotland.

Just as significant were Americans who established another tradition by settling in Britain and buying country houses of their own. The list of American émigrés who played a role in country house life before the Second World War is a long one. William Waldorf Astor, who moved from New York in 1891, became a British citizen in 1899, and bought Hever Castle in Kent four years later, is one early example. There was Lawrence Johnston, a keen amateur gardener whose mother married a Winthrop and bought her son the estate of Hidcote Manor in the Cotswolds; Huttleston Broughton, whose British father had married the daughter of an American oil tycoon, who presided over Anglesey Abbey in Cambridgeshire from 1926 until his death forty years later; Chicagoan Henry “Chips” Channon, whose marriage to heiress Honor Guinness enabled him to buy Kelvedon Hall in Essex in 1938.

To what extent did they have an impact on country house life? They had no wish to import American cultural values. Quite the reverse, in fact. Lawrence Johnston took British citizenship in 1900, when he was twenty-nine, so that he could fight for his adopted country in the Boer War. Huttleston Broughton sat in the House of Lords as Lord Fairhaven; so did William Waldorf Astor as the 1st Viscount Astor. His son Waldorf was a Member of Parliament (MP) before ascending to the House of Lords as 2nd Viscount Astor, at which point his wife Nancy Astor took over his parliamentary seat, becoming the first woman to sit in the House of Commons. Chips Channon was also an MP from 1935 until his death in 1958. He may not have found the peerage he longed for—and how he longed for it—but he at least received a knighthood from Prime Minister Harold Macmillan’s government in 1957. (Channon, who famously described himself as “riveted by lust, furniture, glamour, and society and jewels,” was so anglicized that even his male lover was described as “a classic English queen.”)

So we shouldn’t look for the Americanization of the stately home, for cultural clichés like ketchup bottles at dinner and Stetsons in the gun room. By the 1950s most of the Americans and Anglo-Americans who had acquired country houses were more British than the Brits.

Excerpted from Noble Ambitions: The Fall and Rise of the English Country House After World War II by Adrian Tinniswood. Copyright © 2021. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com