Julieta Silva has a lot of questions about money as she starts college this fall: How do you build credit? How do you keep a budget? What’s the best way to start investing?

“This world revolves around money,” says Silva, 18, an incoming first-year student at Northeastern University in Boston and the first in her family to attend college in the United States. “I want to make sure that I have all of the basics set.”

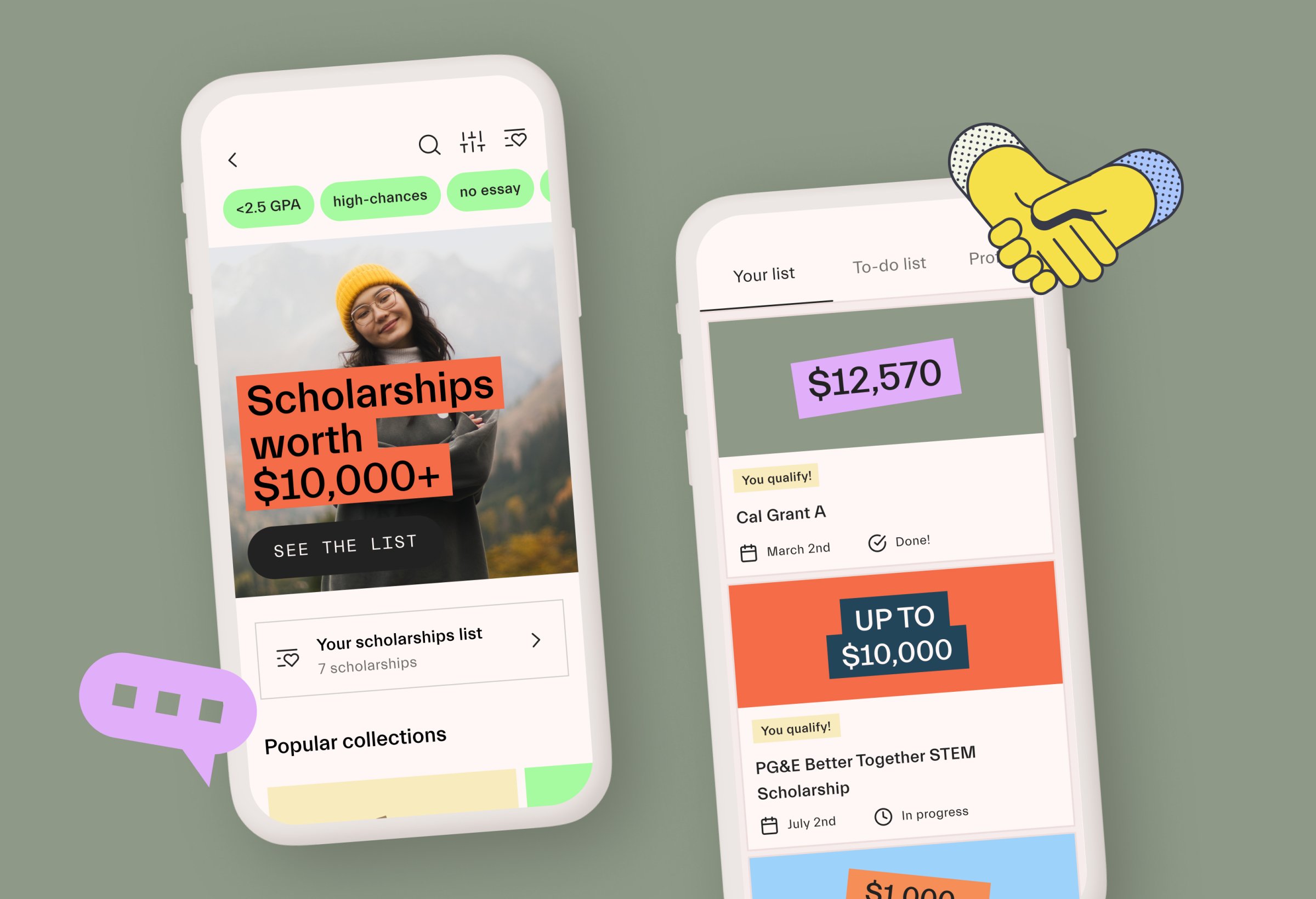

That’s a need the startup Mos is hoping to fill when it launches a banking app for students on Sept. 1. Since 2018, some 400,000 students, including Silva, have used Mos to garner an annual average of $16,430 in college financial aid. Now, the company hopes students who use its financial aid services will stick with the app to manage their savings and investments, take out home mortgages, compare options on auto and other loans, and search for jobs.

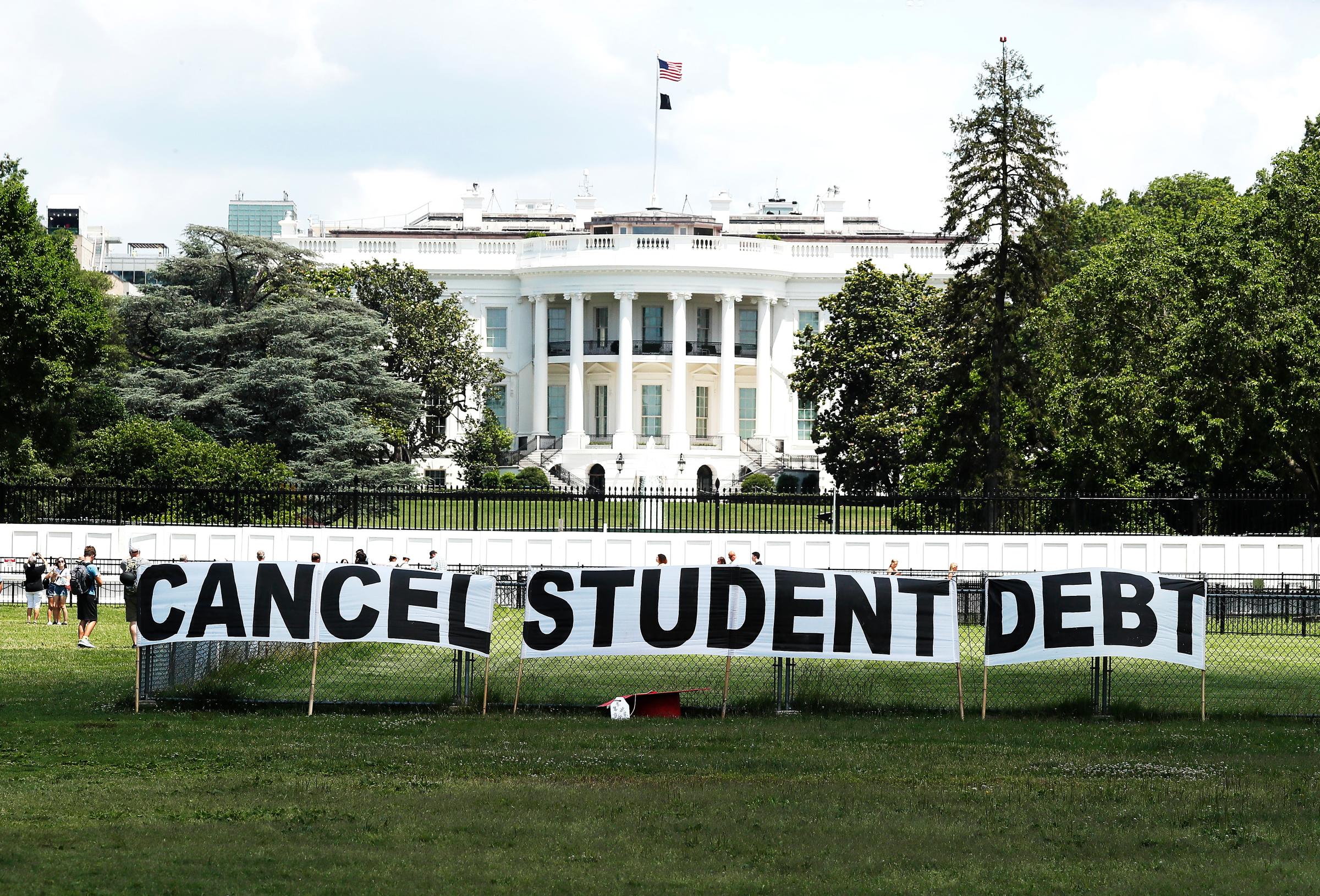

“The goal is not to just become a student bank. The goal is to be like a financial super app,” says Amira Yahyaoui, Mos’s founder and CEO. Yahyaoui, 37, knows how it feels to be a young person struggling to master the often-confusing hurdles of personal finance. The Tunisian human rights activist fled her country as a young adult and lived in exile in France for years without access to a bank account or steady work. (The name “Mos” comes from the Star Wars city of Mos Espa, which was filmed in the Tunisian village where Yahyaoui is from.) “I understand the frustration of not being allowed in because you can’t afford it,” says Yahyaoui, whose goal is to help prevent students like Silva from being dragged into the United States’ $1.7 trillion student-debt crisis. “We are working and targeting and interested in solving the first years of adulting,” she says.

In the face of rising college costs, soaring consumer debt and less confidence in banks since the 2008 financial crisis, Mos is one of several fintech startups that see a need to reimagine banking for a younger generation.

I understand the frustration of not being allowed in because you can't afford it.

Much of Generation Z, born from 1997 to 2012, endured the financial stresses of the pandemic while trying to enter college or the workforce and now face rising education, housing and health care costs. Yet just 21 states require high school students to take a course in personal finance before they graduate, according to a 2020 survey by the Council for Economic Education. That has created an opening for entrepreneurs more in tune with the needs of people like Silva.

The market for digital-only banks or challenger banks—new companies trying to compete with larger, more traditional banks—is projected to grow to $471 billion by 2027, up from $20 billion in 2019, according to a 2020 report by Allied Market Research, along with the rise of digital banking and the closure of more brick-and-mortar bank branches.

“Every single financial product and every type of financial institution is going to be reimagined for Gen Z,” says Anish Acharya, general partner at Andreessen Horowitz who previously worked at Credit Karma, because “they just face much bleaker prospects” than older generations. “Yes, banks offer student loans, but where are the products that help Gen Z to save and to invest, and actually, you know, make an intelligent decision about what loans to take on?” says Acharya, who is not an investor in Mos, but who has advised Yahyaoui.

Read more: Erasing Student Debt Makes Economic Sense. So Why Is It So Hard to Do?

Mos is among a handful of recent startups aiming to capitalize on Gen Z’s combined need for banking services and financial guidance. In May 2020, it raised $13 million in Series A funding, backed by the venture firm Sequoia Capital, with other investors including NBA player Stephen Curry and Zoom founder Eric Yuan.

Greenlight, a kid-friendly debit card that serves 3 million parents and children, hit a $2.3 billion valuation in April with its latest fundraising round. The company promises to help parents “raise financially-smart kids” and includes an educational component where kids can learn about spending and investing. Current, which offers a teen debit card and checking accounts with no overdraft fees up to $100, boasts more than 2 million users and a $2.2 billion valuation.

Akhil Reddy is currently raising seed funding for Bloom, a digital, fee-free bank targeted at Gen Z users, aiming to launch in 2022. The 25-year-old co-founded Bloom with his former college roommate in April, seeing a market in young people frustrated by overdraft fees and by the process of trying to build credit.

“There’s only a few milestones in someone’s life that they will look to change banks. And I think college is a great opportunity,” says Reddy, who got his own bank account for the first time when he started college. “I think Gen Z is starting to realize that if they want to have financial well-being, they need to get on top of their finances and learn how to save, budget and invest.”

Yahyaoui envisions Mos growing as its Gen Z users grow up and turn to it for help paying for college, landing their first jobs and buying their first homes.

Banks made an estimated $31 billion on overdraft fees in 2020. Mos—which is providing banking services through a partner bank, Blue Ridge Bank based in Virginia—is promising not to charge any fees, even after students graduate. Instead, it plans to make money by charging lenders to advertise loans in the app, companies to post jobs or internships and colleges to recruit students.

“Tomorrow, they will get their first job through Mos, first internship through Mos,” Yahyaoui says of her future customers. “They will understand saving, thanks to Mos. They will build credit.”

Silva found Mos when she was beginning the process of applying to college in 2020 and her TikTok feed was flooded with college-going videos.

While she’s a U.S. citizen who attended high school in Brownsville, Texas, her parents live and work just across the border in Mexico, and those foreign taxes complicated the process of filling out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). “My parents didn’t go to college in the U.S., so they don’t know what the college application is like,” says Silva, who sought answers online and on social media.

This world revolves around money.

She stumbled upon a TikTok video posted by Mos about how to apply for financial aid if your parents aren’t from the U.S., which answered many of her questions. It’s one of dozens of TikTok videos Mos has shared with tips about avoiding common FAFSA mistakes, applying to college for free and comparing financial aid offer letters.

From there, Silva paid to use the platform’s financial aid service and was connected with an adviser, who helped her find scholarships that matched her interests and who assisted her in appealing for financial aid from Northeastern. The university granted Silva a financial aid package covering nearly full tuition. She’s now among a group of students advising Mos on what they’re looking for in a bank, and she says she plans to open a Mos bank account.

Silva is one of many students who had little to no financial literacy education in high school. Nearly half of college students say they don’t feel prepared to manage their money, and only 11% of Gen Z students say they have the information they need to repay their college loans, according to a 2019 survey by the insurance company AIG and the online education provider Everfi. In response, lawmakers in 25 states have introduced legislation this year to expand financial education, according to a tracker by Next Gen Personal Finance.

“If [traditional] banks aren’t filling that void, if schools aren’t filling that void, then that’s an opportunity for fintech companies to come in, and that’s what we’ve seen,” says Mark Williams, a finance lecturer at Boston University’s Questrom School of Business, who teaches a class on financial technology and co-founded the nonprofit FitMoney to teach financial literacy to K-12 students in Massachusetts.

Read more: Applying to College Was Never Easy for Most Students. The Pandemic Made It Nearly Impossible

Others argue that financial literacy is an overly simple solution to much larger problems, including the high cost of college in the U.S. “We have a real problem with access to funds for low-income people to attend college. It’s not just that they don’t know what to apply for,” says Timothy Ogden, managing director of the Financial Access Initiative at New York University, who has criticized efforts to require financial literacy courses in high schools. He thinks consumers would be better served if financial education were provided by community nonprofits instead of a bank or a university financial aid office: “Let’s not pretend the banks don’t have motives.”

The most effective kind of financial education, he says, gives people specific information right at the moment they need it to make a decision — targeting high school seniors with lessons about student loans, for example.

That’s something 24-year-old Metztli Uraje could have used when she first entered a four-year university after high school and took out about $3,000 in student loans to pay for it. She later transferred to a more affordable community college to earn an associate’s degree instead and prioritized paying off those loans, squeezing in early-morning and late-night retail shifts around her class schedule.

She resorted to Google to answer all her questions about money — What is interest? When should she sign up for a credit card? What’s required on a FAFSA form? “I think with people that come from first-generation families, it’s really hard to ask for that kind of help because you might not know how to ask, or people in your life don’t know how to do it,” says Uraje, a first-generation college student.

Now a junior at California State University, Dominguez Hills, she is using Mos to apply for financial aid and scholarships, and she wants to avoid taking out student loans again. “A lot of people really don’t know how these forms work, how banks work,” says Uraje, who is hoping a Mos account will offer her more guidance than a traditional bank. “When I first started doing this stuff, I felt like going into it without anyone really helping me.”

While Silva, in Boston, is just beginning her college journey, her interest in personal finance has a lot to do with her post-graduation plans. “I want to travel, I want to enjoy the world. I think that’s a very Gen Z thing to say. But I really, really want to experience that first and then settle down,” she says.

She hopes her newfound wisdom about budgeting, investing and building credit makes that possible. “I don’t want my personal finances or lack thereof to affect that dream that I’ve had since I was little.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Katie Reilly at Katie.Reilly@time.com