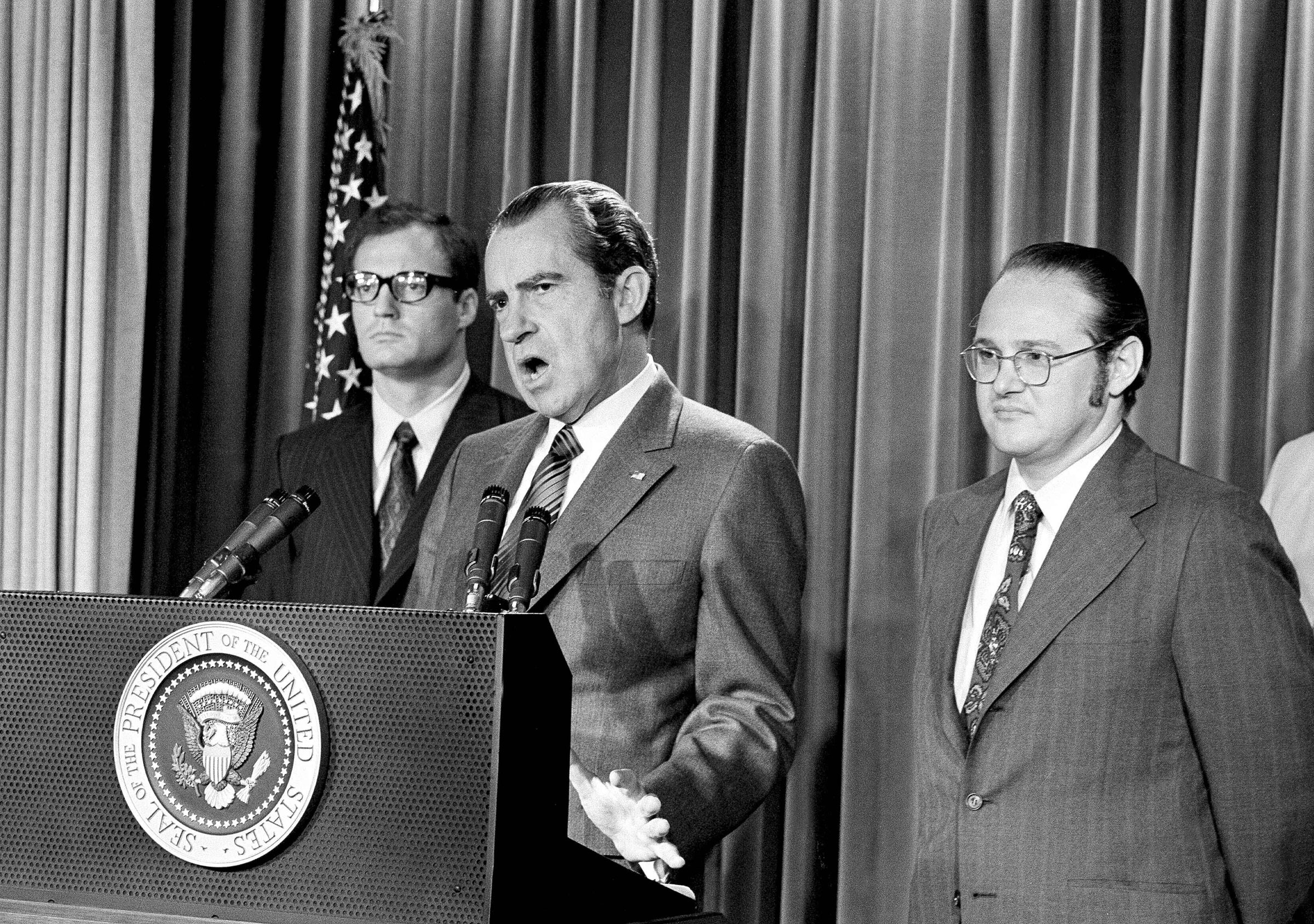

Over fifty years ago on June 17, 1971, President Richard Nixon declared to the Washington press corps that America had a new enemy—narcotics. “America’s public enemy number one,” Nixon claimed, “is drug abuse.” To fight it, it was necessary “to wage a new, all-out offensive.” Within days, U.S. newspapers took up the metaphor. The U.S. was now engaged in a “war on drugs.”

Nixon’s speech marked the beginning of a new era of American drug policy. His announcement would lead to the mass imprisonment of domestic drug users from the 1980s onwards. But the real effect of Nixon’s speech occurred abroad. Here, rhetoric became reality; metaphor got real. Nixon’s speech let drug cops off the leash. And it sparked off a wave of extreme violence, which many drug producing countries in Central and Latin America are still living with today.

Nowhere was this militarization of the drug effort felt more than in Mexico. By the end of the 1960s, the country produced around 90 per cent of the booming marijuana industry. And after the French police raided the heroin factories of Marseilles in 1972, Mexico’s traffickers moved into producing heroin for a growing market of returning Vietnam vets and post-hippy addicts.

From 1971 onwards hundreds of American drug agents descended on Mexico’s border smuggling hubs. First, they came from the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD). And when that folded in 1973, they were agents for the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). They often teamed up with Mexican soldiers and federal police officers (PJF), now flush with money and equipment paid for by the American government.

For fifty years we have known little about this initial campaign or its effects. Most U.S. and Mexican reports were classified. Neither the American agents nor the Mexican drug cops were keen to brag about what they were doing. Yet, over the past eight years I have tried to piece together the reality of this first stage of the war on drugs. My investigation has taken in new declassified documents, the oral testimonies of former cops, drug traffickers and Mexican farmers, and an extraordinary transcript of a 1975 grand jury investigation into BNDD practices. Together, for the first time they offer the grim picture of the effects of Nixon’s words did south of the border.

Officially American agents were in Mexico to pose as potential drug buyers, perform buy-and-busts and then hand over the traffickers to the Mexican cops. But they also employed a host of unsanctioned methods.

The first of these tactics was murder. The Mexican federal cops, in particular, were well known for using ruthless force against traffickers. There were few U.S. agents working south of the border who did not witness at least one fatal shootout or cold-blooded assassination. Some U.S. agents even took part in the killings. One BNDD agent, who worked down in Mexico under future Arizona sheriff Joe Arpaio, described to a grand jury investigation one such incident. One of his colleagues, while working in Ciudad Juárez, ordered another colleague to shoot a fleeing suspect in the back. The colleague refused. So the first agent “emptied the gun into [the suspect] . . . until he was shot to pieces.” According to the former agent, he had heard that Arpaio asked his superiors not to investigate and they agreed.

In addition, the use of torture was extremely common. Talking to DEA agents, reading through Mexican trial documents, trafficker memoirs, and a few, scattered newspaper exposés, it seems there were few U.S. agents who did not at least witness torture. Many encouraged it and many got involved.

The ex-BNDD agent in his grand jury testimony described his shock at the prevalence of the practice.

“Down there, I really got an eyeful. They [BNDD agents] actually participated in the torture—anybody, it didn’t matter a shit who it was. They would actually participate in the torture of these god damn people. I got caught up in a god damn gun fight there myself and killed men. Now we were running into this kind of stuff constantly, all the time.”

After Nixon resigned in August 1974 the DEA pressed the new president, Gerald Ford, to extend these tactics from border towns to the drug-producing villages of Mexico’s interior. The mission involved hundreds of DEA agents, thousands of Mexican cops and tens of thousands of Mexican soldiers. They tracked down opium and marijuana fields, called in helicopters, sprayed the crops with powerful herbicides, and then rounded up the suspected growers. It was known as Operation Condor. But the DEA agents who witnessed it knew it as “the atrocities.” They joked darkly that the federal police commander in charge, Jaime Alcalá García “killed more people than smallpox.”

Recently declassified Mexican secret service documents reveal that in 1978 a Mexican lawyer was tossed into the cells with the Operation Condor drug suspects. He took their testimonies and compiled a report. Even for those of us inured to reading about drug war violence, it makes for disturbing reading. In all, he listed eighteen distinct types of torture, including beating, waterboarding (with chili-infused sparkling water), near-drowning in shit-filled water and rape.

But beyond the victims, this kind of no-holds-barred repression also multiple secondary effects. First, in the U.S., Nixon’s rhetoric (and his successors) pushed the focus from U.S. drug demand to international drug supply. In doing so, politicians now framed the war as foreign conflict which pitched Americans against murderous gangs of overseas criminals. It is a narrative that continues to this day and was central to President Donald Trump’s argument for a border wall.

Second, the war on drugs put torture at the center of Mexican investigative techniques. The logic was as follows. The Americans wanted arrests. Yet drug crime, unlike other felonies, often had no direct victim. Cases couldn’t rely on the testimony of witnesses or complainants. (Few hippies went to the police to complain that they had been scammed buying dope.) So even if Mexican investigators found narcotics, they also needed confessions. To get these quickly and effectively, they employed torture – both physical brutality and psychological threats. And the judiciary acquiesced to the practice. In a series of landmark decisions, the Mexican Supreme Court gave confessions “full probatorial value” regardless of how they were obtained.

Though laws have changed, the logic remains. And most drug confessions are still extracted through torture. In one recent study Mexican academics concluded that between 60 and 70 per cent of suspects experienced torture.

And it didn’t really change anything despite the billions the U.S. poured in and the lives destroyed. In subsequent decades, the big traffickers just moved to cocaine rather than homegrown marijuana and heroin. Now Mexico is responsible for an estimated ninety percent of the cocaine sold to and exchanged inside the U.S. And traffickers have turned their expertise at transnational smuggling to moving other imported narcotics like fentanyl.

Yet, perhaps the most important effect was on the way the trade was managed. Up to the 1970s, corruption was limited. Mexico’s state governors and small-town mayors protected the traffickers, often for a slice of the profits. But they were wary about letting the business spiral out of control. If it did, they could be prosecuted or sacked.

But the war on drugs changed this arrangement. As federal cops and soldiers descended on border towns and drug growing zones, they started to take over the protection of the traffickers. Corruption moved up a level. Police chiefs and even three star generals now ran the protection rackets; they commanded the cartels. And they answered to no one. The U.S. authorities could do little. If the Americans demanded arrests, these new, high-level protectors would simply cough up or occasionally murder a cartel kingpin and let the others continue unmolested.

It is an arrangement that continues to this day. Capturing El Chapo has done nothing to cut drug supply or increase drug prices. Meanwhile the prosecution of former Mexican federal police chief, Genaro García Luna, remains mired in diplomatic disagreements. And last year the former head of the Mexican military, Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda, was arrested but then promptly released back to Mexico by the DEA.

The war that Nixon started shows little sign of stopping.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com