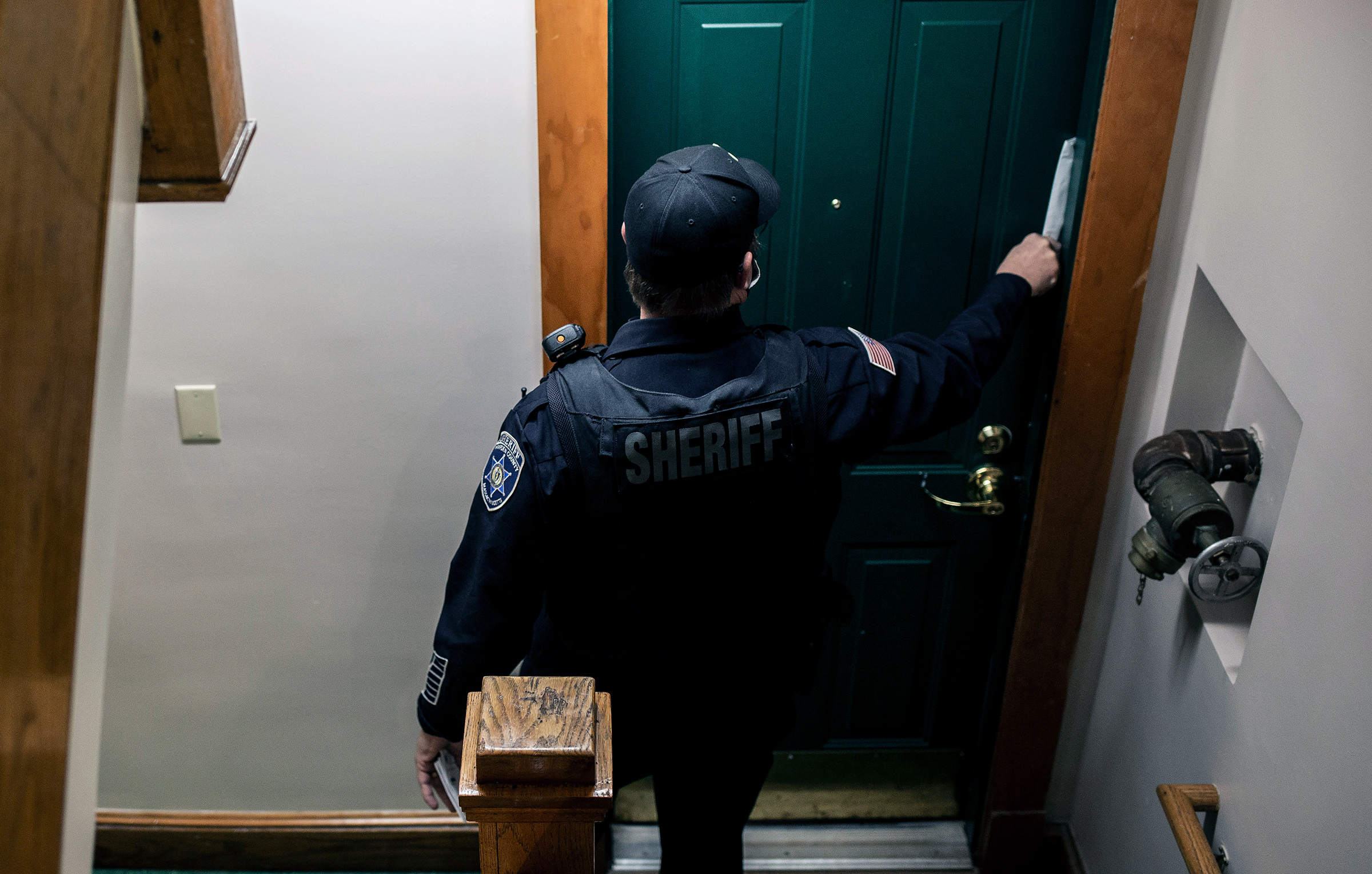

Raven Sullivan is awake responding to emails at 2:05 a.m. She recently received notice that her landlord wants to evict her and her two toddlers from their Georgia rental home over roughly $2,600 in unpaid rent, and she doesn’t want to fall asleep if police officers show up to force her family out in the middle of the night. “I want to be alert,” she says, “if they come and they’re banging on the door to evict us.”

Sullivan, 23, applied for emergency rental assistance through her local government and a charitable foundation, but so far she hasn’t been awarded any. After a federal eviction moratorium imposed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) expired on July 31, she’s running out of time. And she’s not alone: The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a left-leaning think-tank, estimates that 11.4 million renters are still behind on rent payments. But while Congress appropriated $46.6 billion in emergency rental assistance to stave off a wave of evictions, the state and local governments that were allocated those tens of billions of dollars had only spent $3 billion of it by the end of June.

As COVID-19 cases rise in the United States, the expiration of the eviction moratorium grew into a political emergency for Democrats, with open squabbling between Congress and the White House over who had the power to protect the millions of Americans at risk of losing their homes. Progressive Democrats were calling on the Biden Administration to take immediate action to reinstate an eviction moratorium to keep renters housed as local governments continue to dole out the rental relief funds, while the White House tried to punt the problem to Congress instead. As members of Congress pressed the Administration to act, the CDC announced a new eviction moratorium on Tuesday night. This one expires Oct. 3, and only applies in counties experiencing “substantial” and “high levels” of COVID-19 community transmission.

Before the CDC announced its new order, the White House acknowledged the severity of looming evictions as coronavirus cases spiked, largely due to the spread of the highly transmissible Delta variant and sluggish vaccination rates. “Given the rising urgency of the spread of the Delta variant, the President has asked all of us, including the CDC, to do everything in our power to look for every potential legal authority we can have to prevent evictions,” Gene Sperling, the Biden advisor responsible for managing coronavirus relief efforts, said during a Monday briefing. But the executive branch hesitated to act on their concerns, claiming a 5-4 Supreme Court opinion from June precluded the Administration from extending the original moratorium without Congress passing new legislation. “Unfortunately,” said Sperling, “the Supreme Court declared on June 29th that the CDC could not grant such an extension without clear and specific congressional authorization.” The constitutionality of the CDC’s new order is unclear, and it is likely to be challenged in court.

Nearly half a dozen Democratic Members of Congress and Congressional staffers told TIME they disagreed with the White House’s assessment of its authority. Public sparring between prominent Democrats and the White House has so far been rare in this Administration, and it is tension Democrats can ill afford in a moment when their cooperation is essential to getting a $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill through both chambers of Congress.

“We have to understand who has been giving the [eviction moratorium] extensions, and why haven’t they pursued continuing to give the extensions,” Rep. Maxine Waters, Chairwoman of the House Financial Services Committee, told TIME Monday. “The White House, working with its CDC, has been responsible for the moratorium on evictions. [They want you to] think that they can’t [extend] it. Nope, nothing that I have seen legally says they can’t do it.”

The CDC’s decision on Tuesday will likely slow the rate at which renters are evicted from their homes in certain areas, but with a new—and incomplete—moratorium coming in several days after an old one expired, there will likely be more confusion ahead as renters, landlords and courts race to decipher what the new order means, and who has the authority to extend it.

‘It must come from the Administration’

Although both congressional Democrats and the White House seemed unprepared for the magnitude of the problem and their responsibility to address it, the crisis could have been foreseen since last fall.

The CDC moratorium, first imposed by former President Donald Trump in September 2020, was always meant to be a stopgap solution as local governments stood up systems to distribute unprecedented amounts of direct relief funds to tenants whose incomes were impacted by COVID-19 and to the landlords from whom they rented. The Biden Administration extended it for one month for a final time in late June 2021 to give local governments time to dramatically increase their aid distribution.

The extra time proved helpful, allowing local governments to distribute over $1.5 billion in combined rental assistance in June—more than the three previous reporting periods combined. But with tens of billions left to spend, the White House issued a July 29 statement urging Congress to use its legislative power to extend the eviction moratorium in order to give states more time to spread out funds without the added pressure of eviction proceedings kicking off again. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, working with Rep. Waters, tried to build a consensus within their party to pass a vote on extending the moratorium on July 30, but the bid failed to garner support among some moderate Democrats. “Really, we only learned about this yesterday,” Pelosi told reporters afterward, just one day before the moratorium expired. “Not really enough time to socialize it within our caucus.”

Pelosi then kicked the crisis back to the White House. “Action is needed, and it must come from the Administration,” Pelosi and other Democratic leaders wrote in a Sunday statement.

Pointing to a recent Supreme Court opinion, the White House maintained its hands were tied. In a 5-4 opinion on June 29, the court denied a group of landlords and realtors’ request for the court to lift the moratorium early. Conservatives Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh sided with the three liberal justices, and Kavanaugh wrote a one-paragraph concurring opinion that proved crucial to the White House’s position. “In my view, clear and specific congressional authorization (via new legislation) would be necessary for the CDC to extend the moratorium past July 31,” Kavanaugh wrote.

Rep. Pramila Jayapal, chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, says she thinks the White House drew too firm of a conclusion from one line in a concurring opinion on an eviction moratorium “that was written a long time ago in a different circumstance.” Jayapal says. She believes the spread of the Delta variant required faster action from the executive branch. “What we’re talking about is a new extremely virulent variant of the virus that has led to this enormous growth [of cases],” she says, “and we also have statistics now that we didn’t have back then about homelessness and how homelessness increases COVID spread.”

‘It will probably give us some additional time’

After progressive lawmakers including Reps. Cori Bush, Ilhan Omar and Ayanna Pressley slept outside the U.S. Capitol on Friday night to protest the lack of action, and as landlords across the country set out to file eviction notices and orders nationwide, Biden announced the CDC was going to step in despite reservations about its authority.

Not doing anything would be a dangerous threat to public health, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky said in a statement announcing the new moratorium. “It is imperative that public health authorities act quickly to mitigate such an increase of evictions, which could increase the likelihood of new spikes in SARS-CoV-2 transmission,” she wrote. “Such mass evictions and the attendant public health consequences would be very difficult to reverse.”

Speaking from the White House on Tuesday, Biden said he doesn’t know if the basis for the order will pass “Constitutional muster,” but he acknowledged that may not be the point: “At a minimum,” he said, “by the time it gets litigated, it will probably give us some additional time while we’re getting that $45 billion out.”

It’s not clear if Sullivan will be among those who benefit from the additional time, since her landlord has already initiated the eviction process. As she waits to see how her situation plays out, the rising COVID-19 cases in Georgia will likely keep her up at night, too. Georgia’s vaccination rate ranks among the bottom 10 states in the country, and her daughters, ages 2 and 4, are far too young to get the shot.

“I don’t want my kids to be exposed to the virus,” Sullivan says. “I don’t take my kids out unless I absolutely have to take them out.” Maintaining that mantra, however, will become even more difficult if she no longer has a home in which she can keep them safe.

With reporting by Brian Bennett/Washington

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Abby Vesoulis at abby.vesoulis@time.com