Since January, U.S. financial markets have been on a tear, a wild ride that began as the Biden administration completed its first full week in power. Five months later, the benchmark Dow and the wider S&P indexes have reached record highs, while individual assets have behaved…well, exuberantly, most spectacularly in the sudden 1,200 percent rise and 40% drop in the price of Dogecoin, a cybercurrency initially launched as a joke.

Most nervous-making for market historians, the price-to-earnings ratio for the S&P 500 had climbed past forty four by mid-May—almost three times its long-term average of about sixteen, and remains around 40 today. That means it now costs about forty dollars to buy one dollar of the earnings of the five hundred largest U.S. companies, a level seen in previous market panics.

Such data has prompted comparisons with the lead-in to 1929’s Black Friday crash. Nobel laureate Robert Schiller pointedly drew that link in April, writing that in the late 1920s, and by implication, again today “people played the market as a grand game abetted by technological innovation and new mass media.”

Yet, while popular enthusiasm played its part in 1929 and in crashes before and since, there is a story from the earliest days of financial capitalism that suggests the problem isn’t just that sometimes some people act foolishly. It is rather that money manias reliably and systematically evoke such folly.

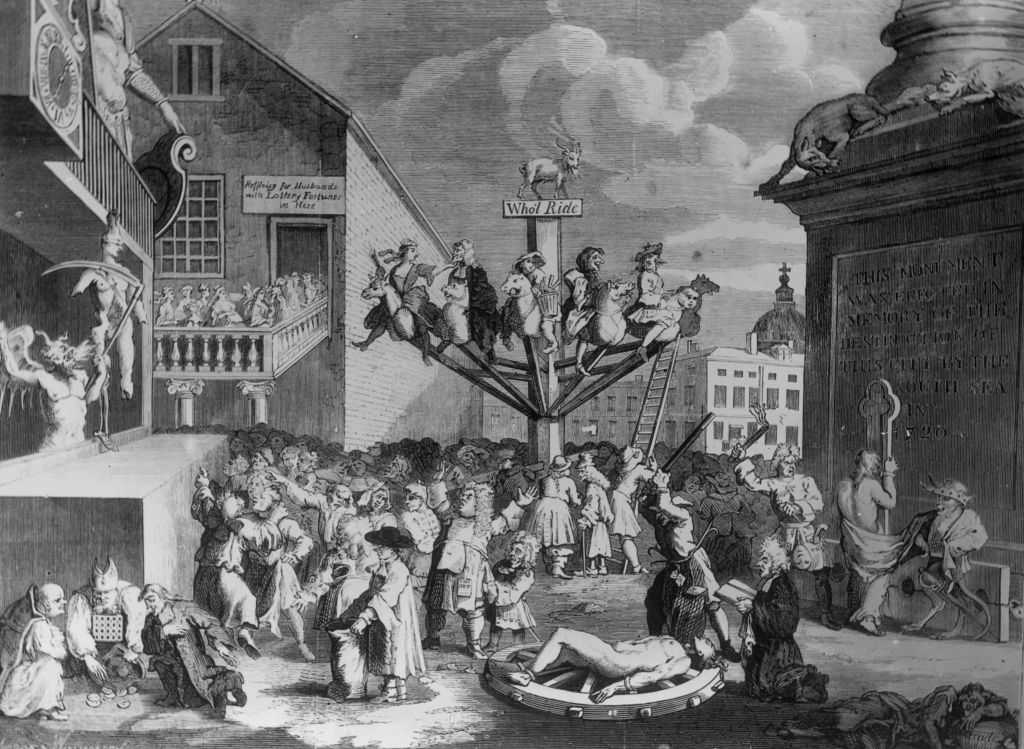

The first boom and crash took place in London in 1720, in what we now call the South Sea Bubble. Those who lived through describe scenes of madness—along with misdeeds, con-men ruining honest, simpler folk. Such tales reinforce the idea that it is individual mistakes, not market failures, that produce crashes. But there is a story of two men, both experts, each with very different approaches to deciding what the market was worth, that reveals a deeper pathology within financial disasters, then and since.

Their adventure began in January, 1720 when the Britain’s government struck a deal with the South Sea Company. The Company had been founded nine years earlier to lend money to the Treasury, while receiving in return a monopoly of the kingdom’s trade in goods and slaves with Spanish America. In the new deal, the Company would be allowed to issue new shares, exchanging them for British government bonds, a mountain of debt created over three decades of war. Those who agreed to swap their bonds for shares would then get a reduced dividend in place of their regular bond payments, plus a fraction of hoped-for profits from the trans-Atlantic trade.

As soon news of the bargain leaked, South Sea shares started to climb, tripling from January to April. That swift jump did not raise any red flags. The journalist Daniel Defoe, fresh off his triumph with Robinson Crusoe, wrote in April that “the present rate of stock is far from being exorbitant,” and that boldness was all: “A man that is out of the stocks,” he added, “may almost as well be out of the world.”

Demand for South Sea shares accelerated through that spring, until it reached its peak in late June: £1,000 (well over £100,000 in 21st century money), up almost nine times in the year.

We know now that such a price for the actual economic activity represented by South Sea shares was absurd, unsustainable. But could anyone living through the frenzy have figured that out before the crash?

Read More: NFTs Are Shaking Up the Art World—But They Could Change So Much More

Yes. At least one person did: a member of Parliament and a fellow of the Royal Society named Archibald Hutcheson. In the spring of 1720 he built something no one else had: a mathematical model that enabled him to calculate whether the South Sea Company could make enough money to justify its stock price—at any level the market might reach.

His answer never changed. It could not. From the moment the Company began to sell its new shares to the public at its mid-April level of £300, Hucheson’s model gave the same answer: there was no plausible way the Company could sell enough slaves and stuff to justify that price.

As market climbed, he repeated that calculation, each time showing a widening gap between the South Sea stock price and the likelihood of the Company earning enough to match the return from other, safer investments–like the government bonds investors were racing to convert into Company stock.

Finally, when South Sea shares blew by £500, Hutcheson gave up. No one cared. Given “this blazing and astonishing meteor,” he wrote, mere numbers could not keep folly at bay. In time, perhaps, “people… may then begin to think more coolly about this Matter, and hearken a little to Reason and Demonstration.” That day would come, but not yet.

To be fair to those who would lose so much in the coming months, the concept of applying math to the stock market was still brand new. It was even unfamiliar even to the man who had created much of the mathematics that describes change over time.

In 1720, Isaac Newton was an experienced investor, with a broad portfolio that included government obligations, shares in the Bank of England, the East India Company and South Sea Company itself. At first, he played it safe, selling his South Sea holdings by May, booking a significant profit, millions in 2020 terms.

Then, as the market continued to rise, he second-guessed himself. What he’d “lost” by not hanging on as South Sea shares approached £1,000 gnawed at him. A few weeks after selling, he gave in, buying shares again right at the June peak. He bought yet more in mid-August with the market still near its highs.

Newton was hardly alone in such behavior. His story was repeated over and over again that summer—and since in booms and busts into the 21st century. Experiencing or witnessing sudden gains engenders money manias. During that first great Bubble, the seemingly unstoppable rise of South Sea shares persuaded thousands who had no prior experience of financial markets that the appearance of sudden wealth was normal, and permanent. For just one example, in May 1720, a minor government official named James Windham wrote to his mother that “I grow so rrich so fast that I like stock jobbing of all things.” Of no prior wealth, he was now in a position, he said, to turn himself into gentry, buying land worth, in 21st century terms, between £1.5 and £3 million.

Newton’s experience is exemplary, that is, not unique. It’s the same psychology that makes casinos work: the emotional power of money, the chance at a fortune encourages behavior that on paper looks risky, or even crazy.

The collapse started just three weeks after Newton’s second purchase. By early October, the Company’s shares had lost 70% from their top, hitting pre-Bubble levels by Christmas. Windham lost all he had and more. Like Newton, he had risked more money in August, then lost it all. By December, he was bankrupt, and told his brother that he would seek his fortune along the usual path for an undone Englishman: “The sea is fittest for an undone man,” he wrote, “so I’m for that.

Newton survived the crash in better shape. By his reckoning, he lost something over £3 million in 21st century money, but retained as much or a little more in other investments. Still, the loss was a blow, as much to his pride as his purse. He would later tell his niece, “I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.”

For “the people,” read Newton himself; it was his own errors that cost him so dearly. But why had he been so reckless? There was no one else in London — probably, no one alive anywhere in the world — better equipped to do the math on the Company’s prospects. How had he missed what Hutcheson, with nowhere near Newton’s mathematical brilliance, plainly understood: that it is possible to quantify questions of risk and value.

The answer is that Newton, for all his smarts, was human. The events of 1720, 1929, and, quite possibly right now, show that booms always overwhelm reason; markets are not always rational.

The Bubble year echoes in this spring of 2021. Several companies, most famously but far from uniquely, Gamestop, have seen their own mini-bubbles rising to levels far above what their businesses were ever worth. And the more recent wild swings in Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency markets offer rides as wild as anything Newton and his contemporaries experienced. There are plenty of individual choices within each of those boomlets, but the problem isn’t personal, it’s systematic. If even the greatest scientific thinker of his day, and maybe ever, could not master his emotions during a money mania, what chance do all the rest of us have?

Ultimately, the fact that humans predictably behave foolishly during market extremes is why finance needs regulation. No rule can stop individuals from making reckless choices, but since 1929, regulation has been shown to be capable of reducing the risk of catastrophic consequences for both individuals and the financial system as a whole. A simple measure like the increase in margin requirements—how much money a broker can lend to a client to buy shares—limits, though it definitely doesn’t eliminate, the amount of damage that can flow from a single speculative decision.

There are analogous safeguards after various crashes have been imposed on major players in the markets as well. But in time, each disaster fades from memory, while new market techniques emerge without a companion increase in vigilance—which is what lay behind the most recent major financial crisis, the Great Recession that followed the market crash of 2008. Newton and his fellow losers in 1720 could plead one mitigating factor for their folly: they didn’t know what was happening to them in that first market catastrophe.

Three centuries later, we do not have that excuse.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com