Cody Howard is standing at a makeshift pulpit under an overpass preaching about the COVID-19 vaccine. The pastor of a congregation he calls Church Under the Bridge, which serves the homeless of Texarkana, Texas, Howard delivers a crucial message: he got the shot. He admits that science and the authorities aren’t yet 100% sure about “the long-term effects of this thing,” and emphasizes that every person can make up their own mind. But he says his own decision to get vaccinated was a response to a question posed by a core tenet of Christianity: “Will it help my neighbor?”

Plenty of the three dozen or so attendees on this rainy June morning are skeptical. “When [COVID-19] first started spreading, they said it’s like a high-powered flu or pneumonia,” says Tony Wood, referring to comments like those made by former President Donald Trump, “and I’ve had pneumonia.” Others appear supportive, but none act on the pastor’s sermon. Howard, undeterred, gestures to a mobile vaccine bus parked nearby from the Christus St. Michael Health System, a local hospital group, his long hair, lanky build and red T-shirt evoking a casual Christlike figure leading his flock.

What Howard’s listeners don’t know is that he is carrying a message from a less divine source: the federal government, or more specifically the White House. The Christus health system is a member of the Catholic Health Association of the U.S. (CHA), which is part of the COVID-19 Community Corps, a Biden Administration effort to persuade hesitant Americans like Wood to get vaccinated. The corps is a loose network of more than 4,000 organizations meeting regularly with the White House to share information on vaccines. The faith leaders, community groups and physicians who make up the corps receive data, tool kits and talking points from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and tailor them to specific communities across the country.

The experiment may be the Biden Administration’s best hope to beat COVID-19. The U.S. must fully vaccinate at least 70% of its population to contain the virus, public-health experts say. As of June 21, CDC data show that even among those eligible for a vaccine, the country remains 17 percentage points short of that goal, which experts believe will bring what is known as herd immunity. As some Americans resist getting the shot, average daily vaccinations have slowed from a high of 3.4 million in early April to slightly over 850,000 in mid-June. With new strains emerging around the globe, including the faster-spreading Delta variant, millions of American lives are potentially at risk, says Dr. Krishna Udayakumar, director of the Duke Global Health Innovation Center. “We’re going to have to increase the rate of vaccinations in the U.S. in order to avoid another surge,” he says.

Biden has staked the success of his first year on getting enough people vaccinated to reopen society, saying this spring he wanted 70% of the adult population to have at least one shot by July 4. He has also declared the larger goal of showing Americans that the federal government can be a powerful force for good. The COVID-19 Community Corps sits at the uneasy crux of those two objectives: How can the federal government persuade people who don’t trust the federal government to get vaccinated? Through the corps, the Administration thinks it has found a way, by filtering a federal message through trusted local sources. But building trust is hard. Howard, for instance, says he has to avoid emphasizing any ties to Washington. “The more that we put that out there,” he says, “the more distrustful they are.”

Person by person, the corps is trying to chip away at bitter politics and entrenched resistance to federal intervention. While polling shows that vaccine hesitancy has declined since Biden took office, it’s difficult to quantify how much can be attributed to the corps. But if the program works, it could save lives and usher in a post-pandemic reality where Americans have a rebuilt faith in federal leadership. “You can lead in government by being at the forefront and being the loudest voice in the room,” says Surgeon General Vivek Murthy. “But you can also lead by supporting leaders and communities and giving them the tools and resources, information and support that they need.”

Less than a week before the Inauguration, when vaccines were still restricted to the most vulnerable, and even they were frantically refreshing their computer browsers to find appointments, Biden’s COVID-19 response team was planning for the days when there would be too many vaccines.

Courtney Rowe and Ben Wakana, the officials in charge of the White House’s COVID-19 communications strategy, knew that by spring, a surplus of shots would make hesitancy the biggest barrier to vaccination. Research they conducted during the presidential transition showed they needed local leaders from churches, social-service agencies and hospitals to mitigate the problem. But they also needed unified, top-down messaging to counter disinformation about the vaccines.

They decided these two strategies could work in tandem. The White House could recruit grassroots organizations to persuade hesitant Americans and arm them with information from the federal government. It was a risk, says Wakana. “The government hasn’t really played this role before.”

Wakana and Rowe spent the winter monitoring polls about hesitancy. They found minority, rural and evangelical communities were the most skeptical, and they began drawing up lists of recruits, from the NAACP, NASCAR and the American Red Cross to the National Association of Evangelicals, the American Farm Bureau Federation and the Black Women’s Roundtable. By March 27, they had more than 200 names. Administration officials designed invitations on White House letterhead asking them to be founding members of a corps that would “share science-based information directly with community leaders and organizations across the country,” according to a copy reviewed by TIME. Wakana thought they would receive 50 positive responses. They ended up with over 275 founding members.

Walter Kim, head of the National Association of Evangelicals, was among those who immediately signed on. He was impressed by the Administration’s desire to engage evangelical Christians, even though three-quarters of them had voted for Trump in the 2020 election, according to exit polls. “I’ve appreciated in this Administration the recognition that we are going to have to partner with a lot of different types of people, regardless of their political affiliations,” he says. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s latest tracking poll, 27% of Republicans say they will “definitely not” get vaccinated, compared with 3% of Democrats.

On April 13, the two-week-old corps faced its first big test. As states expanded vaccine eligibility to all adults over age 16, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and CDC temporarily paused the use of the Johnson & Johnson (J&J) vaccine after six women who had taken it developed severe blood clots. Local health officials, especially those in rural areas where J&J’s single dose held particular appeal, were afraid that the news would stoke hesitancy. Within hours of the pause, the Administration mobilized the corps. Murthy convened more than 1,000 members for a Zoom call led by Dr. Anthony Fauci, and circulated a letter explaining that the blood clots were incredibly rare and that the pause embodied the Administration’s careful approach.

For corps members like the CHA, having quick access to answers from the CDC and the FDA was crucial. Brian Reardon, vice president of communications and marketing at the CHA, had already been working with a group of about 50 other Catholic organizations to share COVID-19 vaccine talking points, and soon after the J&J pause, he sent them several links to reliable, updated information. “It’s a matter of organizing our communication and being consistent,” he says.

In late April, when corps members told the White House that some in their community were worried about the vaccines’ quick production, Murthy organized a Zoom call with Kizzmekia Corbett, an immunologist at the NIH who helped develop the Moderna vaccine, to explain how the mRNA technology in the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna shots had been in the works for over two decades. When the FDA authorized the Pfizer vaccine for emergency use in adolescents, Murthy gathered hundreds of parents, youth-group leaders, pediatricians and educators on a May 19 virtual roundtable to talk about the change.

“When we thought about the Community Corps,” says Murthy, “we always in the beginning thought of it as a bidirectional channel, a place where not only would we have information to share but also where we would have the ability to learn from people and they would also have the ability to teach each other.”

And in some places, it has worked.

Renea Jones Rogers knew her livelihood depended on getting more than just herself vaccinated. This spring, the second-generation co-owner of a 600-acre tomato farm in Unicoi, Tenn., started receiving newsletters, emails and social media updates about the COVID-19 vaccines from the American Farm Bureau, a founding Community Corps member. Jones Rogers, who is her county’s local farm bureau president, had already been vaccinated, but most of her employees, who come from Mexico using the guest-worker program each year, do not speak English and aren’t familiar with the U.S. health care system. If they didn’t get vaccinated, that could mean close to 200 people on her farm still vulnerable to COVID-19, potentially spreading it among themselves and in the small town nearby.

In April, Jones Rogers contacted her regional health department to bring vaccines to her farm, and so far every one of this summer’s roughly 80 workers has been vaccinated. Arturo Gamiño was one. He doesn’t like needles, but he had seen people die “very ugly deaths” from COVID-19 last year, he says through an interpreter. After he received a Spanish-language printout from the CDC explaining how mRNA vaccines work, he rolled up the sleeve of his white work shirt one morning in June to get his shot.

But Jones Rogers’ story may be more the exception than the rule. With just 36% of its residents fully vaccinated, Tennessee is still in the bottom 10 states in the country by that metric. And other Community Corps–aided efforts are moving much more slowly.

Back in Texarkana, the Christus health system faces its own obstacles. Just 25% of people over age 12 in Bowie County, where Texarkana is located, have been vaccinated. Christus’ doctors and faith leaders adapt information from federal officials for the heavily religious community. But they had to close their mass-vaccination site by the first week of May because interest was drying up. That was one reason they partnered with local leaders like Cody Howard, the street preacher who is also the executive director of Mission Texarkana, which serves the small city’s poor and homeless community.

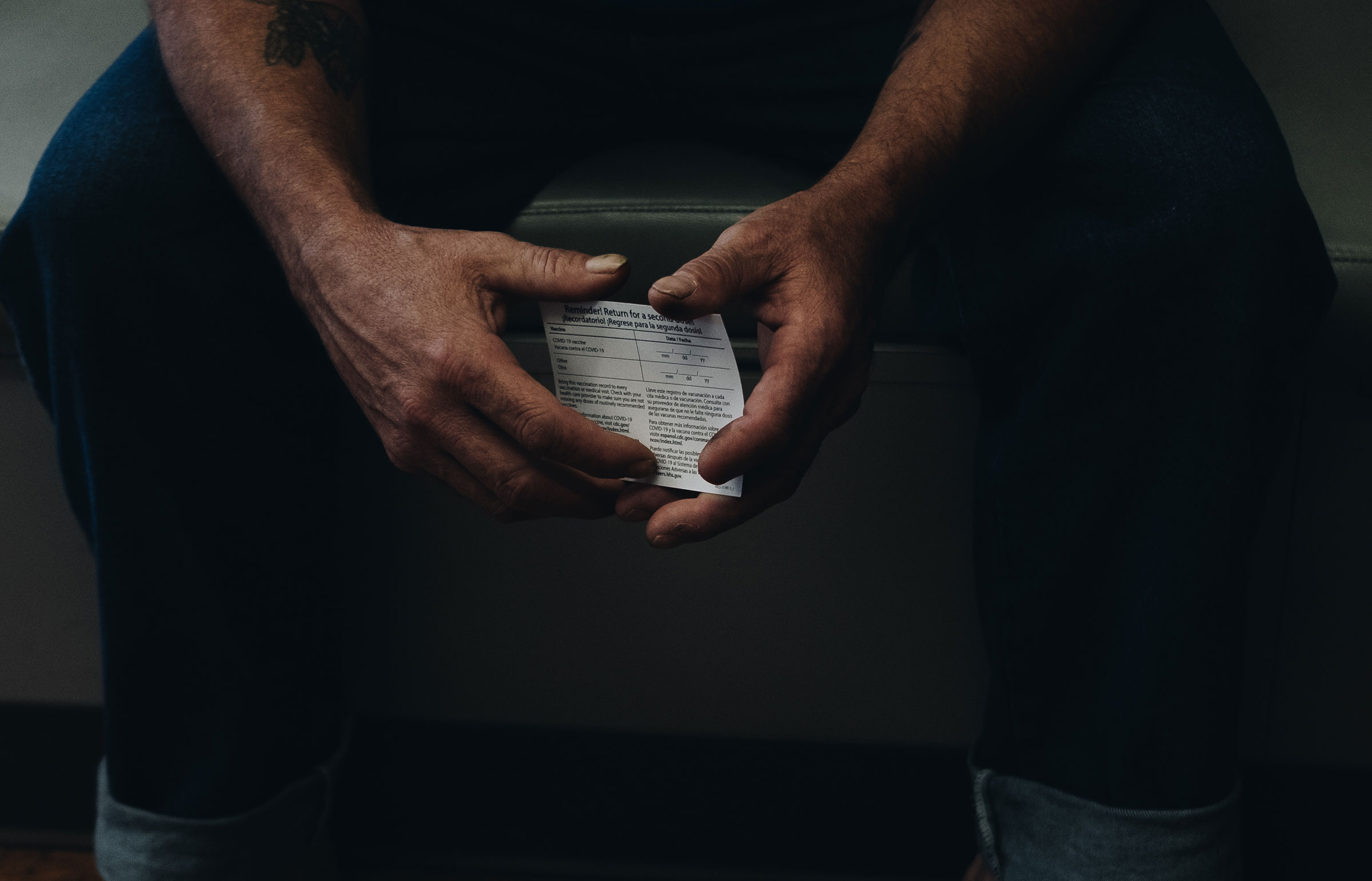

After Howard’s rainy June church service, the Christus vaccine bus heads over to a nearby homeless shelter. There, James Hunt ambles up to the bus. He says he is excited to get the vaccine so he can stop wearing a mask when he stays in the shelter. The team answers his questions, and he leaves the vaccine bus with his packet of CDC-approved information, a lollipop and a grin, mask around his chin.

But for all of the preaching and educating and mobilizing, a half-day of effort in Texarkana has resulted in vaccinations for just six people. Wood, the skeptical worshipper from the morning’s service, isn’t among them. “I know just about everybody from the mission, and they’re all wonderful people,” Wood says. But he’s still wary that he could get sick from the COVID-19 shot itself, despite the day’s assurances that it is safe. “I know some people who took it, and they had no problems with it, but …” he trails off. “I don’t want to take the shot.” -With reporting by Alejandro de la Garza

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Abigail Abrams/Texarkana, Texas at abigail.abrams@time.com and Alana Abramson at Alana.Abramson@time.com