Emails from weird addresses. Messages caught in a spam filter. A life-changing phone call. The most recent recipients of donations from pioneering billionaire philanthropist MacKenzie Scott and her husband Dan Jewett tell remarkably similar stories of the unusual and secretive process through which they receive once-in-a-lifetime, transformative amounts of money.

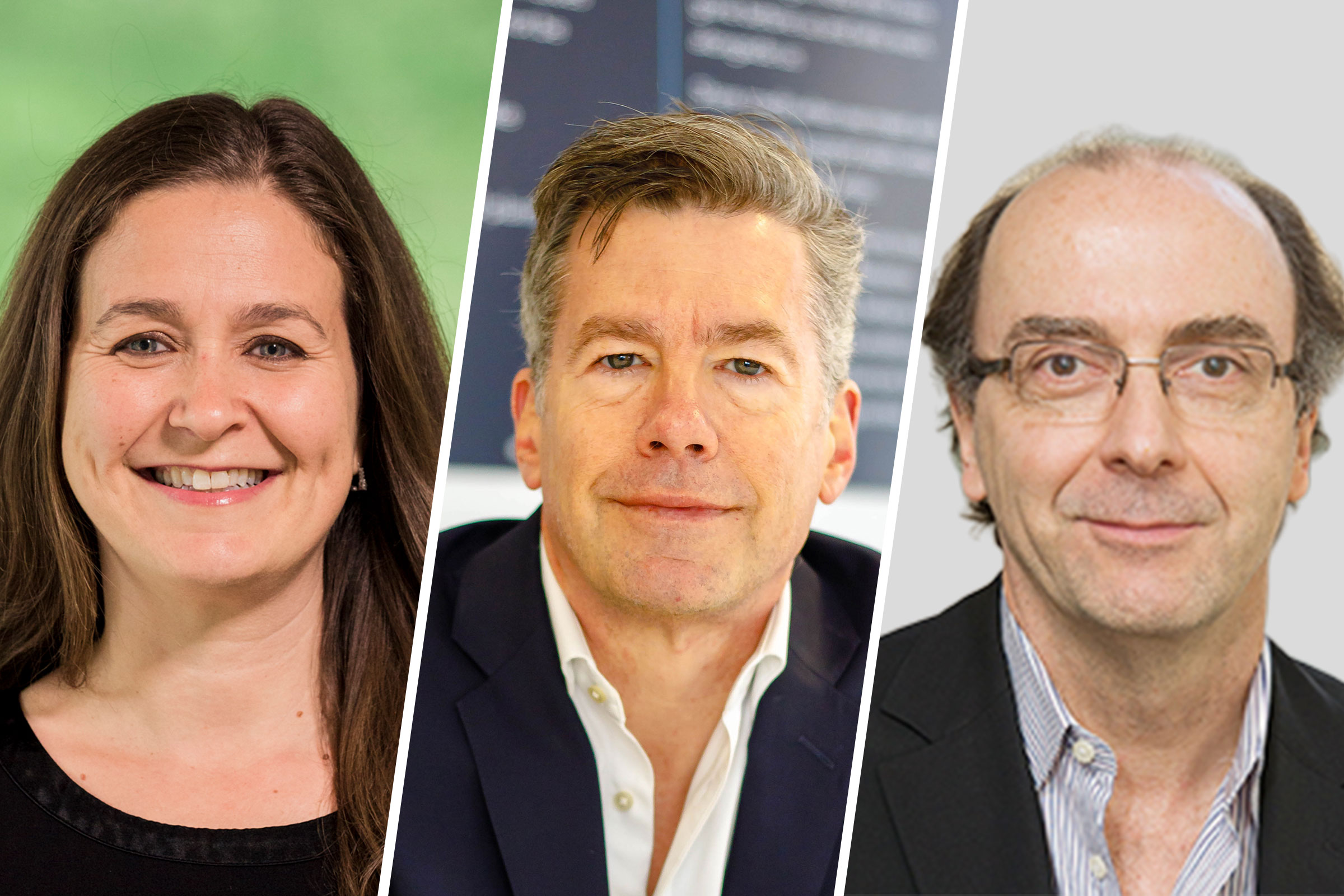

“When I got the call, I literally just lost my breath,” says Cindy Greenberg, president and CEO of Repair the World, a faith-based organization that promotes local community service among Jewish youth, to which Scott gave $7 million in mid-June. “As [Scott’s representative] told me the amount of the gift, I felt all the breath come out of me. And when she had finished speaking, I said, ‘Can you please repeat that?’ It was such incredible news, I felt like I had to hear it a second time.”

Brad Smith, president of Candid, an organization that promotes transparency among philanthropic groups, on the other hand, says he almost missed the first email requesting a call. “I was actually contacted by somebody else who said, ‘There’s someone trying to get in touch with you about this and maybe their email got caught or something. Please have a look?'” Once it was all straightened out and he discovered his organization was getting $15 million, he says he was surprised by how close he came to crying.

For Nick Grono, CEO of the Freedom Fund, a global anti-slavery organization, it took a little longer for the news to sink in. “I got emotional when I got the news that the money was actually coming through,” a few days before the public announcement, says Grono, whose group was given $35 million. “You know, I’ve dedicated my life to working on these issues and making an impact and suddenly… .” He is unable to finish the sentence. “We can make huge change because of this and I’m so deeply grateful,” he says.

On June 15, approximately six months after her last round of giving, Scott announced that she and Jewett had just donated a total of about $2.7 billion to 286 organizations. This group of recipients reflect some new priorities for the couple: cultural institutions such as Ballet Hispánico and the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater were included for the first time. More faith-based organizations were on the list. And the giving moved beyond the borders of the 50 U.S. states, spreading the wealth to such outfits as Ushahidi in Kenya and Piramal Swathya in India.

Read More: MacKenzie Scott Gave Away Six Billion Dollars Last Year. It’s Not As Easy As It Sounds

While the Scott process for giving is unusual from beginning to end, what the recipients find most revolutionary is how little control the donors want over the money. The funds are unrestricted, which means they can be spent as the recipient sees fit. “Unrestricted funds mean you can take risks and that’s what’s so exciting about it,” says Grono, whose organization works with more than 100 other organizations around the world to build communities that can resist slavery and trafficking, and which has plans for bolder programs that are generally harder to fund. “You know there’s always a risk that the money won’t be spent effectively, but she’s happy to take that risk.”

To many philanthropic leaders, this way of giving reflects a deep trust in them and the work they are doing. They speak of it not just as a very useful chunk of money but as a recognition that their work is meaningful and effective. “I was in awe of [Scott’s giving]” says Greenberg. “But I never imagined I would be on the receiving end.” She plans to use the funds to promote service as a central part of Jewish life and to expand her program’s service partnerships to six new communities.

Smith says many foundations and grant makers don’t understand what Candid does, or do not consider it a worthy cause. “A lot of donors, new and old, don’t really appreciate the importance of what she called ‘social sector infrastructure’ in organizations like ours that are on the supply lines for the groups that are on the frontlines,” he says. “We provide information, we help them get funding, we connect them, donors are able to research them.” He believes having Scott recognize them—she funded several other similar organizations—and write about why in her Medium post will be a game changer.

As in previous cases, nobody applied for these grants. They were just selected to get one. “She’s not burdening the organizations with tons of paperwork and proposals and theories of change and KPIs and going through a long, long process of providing tons of information,” says Smith. After the donation is given, the organizations have to provide a three or four page report on how the money was spent and what they learned for the following three years. This adds to the feeling among the grantees that they’ve earned the funding, but it’s more like an award than income.

For those counting at home, Scott has now given away about $8.6 billion to 786 recipients since she announced her first gifts in July 2020. And because Amazon’s stock price keeps climbing, she has even more to give than when she started. If she keeps up her current pace and frequency, she should be making another 220 or so charitable organizations more financially robust by the end of this year. Non-profit folks, check your spam filters.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com