Following the terror attacks that took place Sept. 11, 2001, people across the country began searching Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary for the same word. The word was not “rubble,” or “triage,” or even “terrorism,” but “surreal.” And they did the same thing again after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School. And again, after the Boston Marathon bombing.

In March 2020, when many cities were preparing for stay-at-home orders because of COVID-19, the fear and uncertainty of the moment surfaced in the dictionary’s top searches. People were looking up technical words, such as “pandemic,” “quarantine,” and “virus.” But they were also looking up philosophical ones: searches swelled for “apocalypse,” “Kafkaesque,” “martial law,” “calamity,” “pestilence,” “contagion,” “well-being,” “hysteria,” “hoarding,” “self-isolation,” “vulnerable,” “unprecedented,” “triage,” “essential,” or “poignant.” And of course: “surreal.”

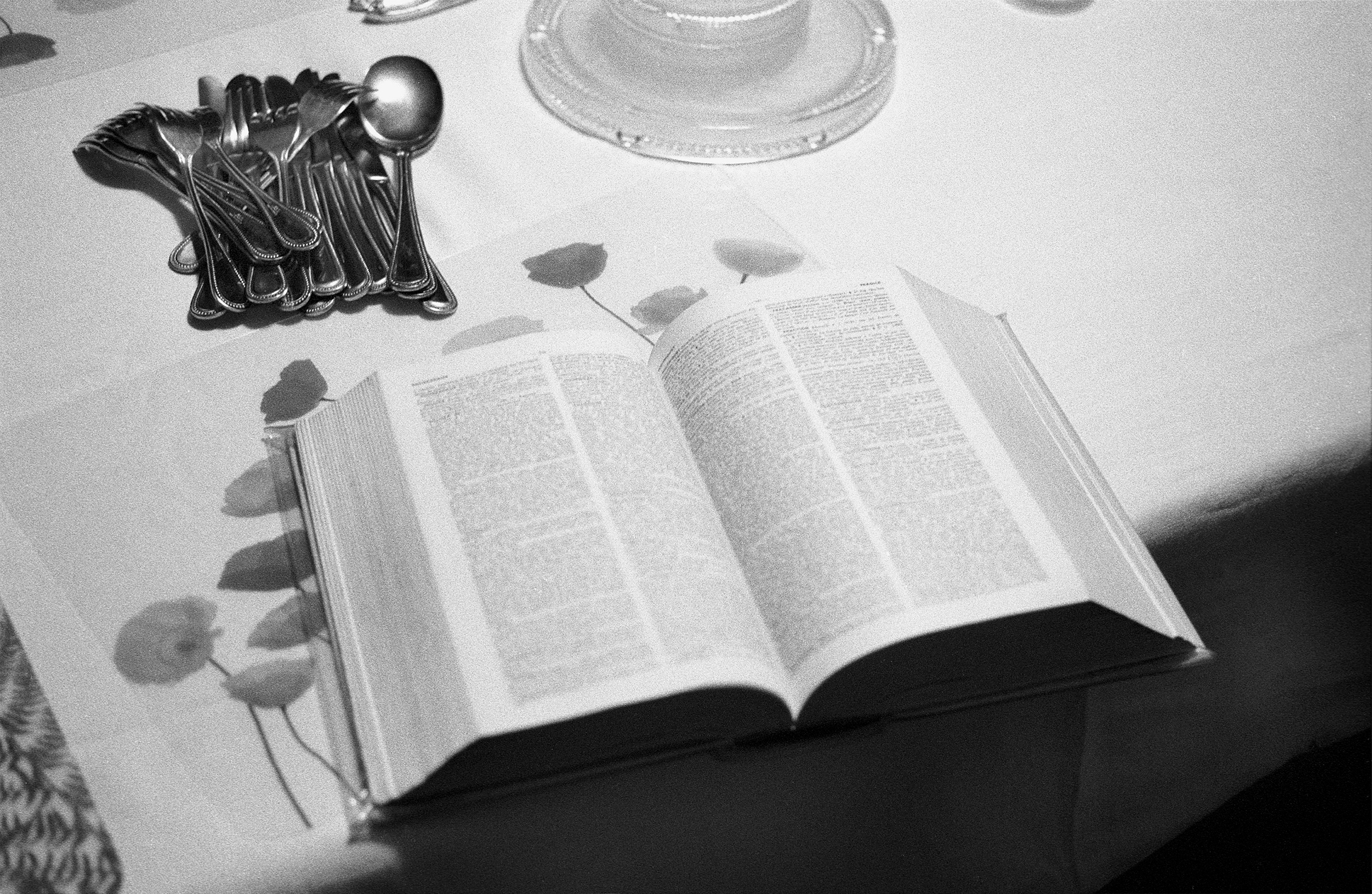

Merriam-Webster’s definition for “surreal” is an adjective meaning “marked by the intense irrational reality of a dream,” or “unbelievable.” We might think of a dictionary as an objective tool, a book that provides the meanings of words. However, readers were using it for something else entirely. “People were turning to the dictionary not for facts but for what I would call philosophy,” Peter Sokolowski, editor-at-large at Merriam-Webster, said of these moments of crisis. “You’re trying to wrap your head around an idea or phenomenon, and you go to the dictionary to go back to basics.”

The dictionary offers its readers clarity, especially when grappling with events that feel inconceivable. Whether in the form of violence or disease, trauma can upend our understanding of life. Moments such as these do more than make us fear for our physical safety: they shake our sense of order, rattling our understanding of the world and the way we believe it should function.

Reference books such as the dictionary return us to a domain in which things have their place: information is methodical and organized, and the answer to any question can be found, if only we know where to look. Our humble dictionaries, almanacs, cookbooks, and how-to books have served this quiet purpose for centuries: functioning as a refuge from ambiguity in times of turmoil. These American “bibles,” those dog-eared books for daily life, are the unexamined touchstones of American society. Those books, which sold tens of millions of copies, addressed the challenges, conflicts, and insecurities of their time.

The dictionary has served so many different purposes throughout history: reference guide, judge, schoolteacher, even moral arbiter. Whether it was Noah Webster trying to construct a patriotic American identity using language, or Frederick Douglass picking up a Webster book to teach himself to write and to secure his freedom, Webster’s work has long been more than a shelf ornament.

Today, the editors at Merriam-Webster have been asked to serve as friend, guide, and philosopher for contemporary readers, functioning as a kind of “public utility,” Sokolowski said. Truth and understanding may vary based on age, geography, what media you consume, and what your political affiliations are, but there is a bridge to be found in online dictionaries in particular, a broadening of the exchange between readers and lexicographers—and even among readers themselves. The definitions of words may change over time, but a word still exists to describe phenomena we don’t understand, and its definition can be found. Now, we need only an Internet connection.

Sokolowski told me repeatedly that the dictionary is “neither an accusation nor a diagnosis.” I’d contend that it can be both, but it can also serve a different purpose: it can take the pulse of the population, expressing some anxiety or national trend through a surge of interconnected words and their web of meanings.

This impulse to define—especially in moments of chaos—sometimes seems an attempt to avoid the messiness of mourning. The reaction to many of these events is confusion, followed by disbelief and even rage. If national grief were to be boxed into the Kübler-Ross stages, Americans are often stuck in the first three: denial, anger, and bargaining. In the word “surreal,” there is a refusal. By understanding tragedy as “surreal,” we seem to be saying “this cannot really be happening.”

It’s why so many of these “surreal” incidents—whether 9/11 or Sandy Hook—have become ripe for conspiracy theories. Some people find more solace in refusing to believe that these events could and did happen. To this swath of Americans, even a shadowy cabal of puppet-masters is easier to stomach than the idea that a plane could be hijacked mid-air, or that someone could walk into an elementary school and massacre children.

So those who accept these events as true are forced to look for other kinds of answers. The searches for words seem to be asking much deeper questions: How could this happen? And why?

The birth of the word surreal itself came out of those same questions. French poet Guillaume Apollinaire first invented the word “surréalisme,” from sur– meaning “beyond” and réalisme meaning “realism.” The ensuing surrealist movement was a direct response to the chaos of World War I, as artists reckoned with the loss of so many millions of young lives and continued to grapple with the trauma of the ensuing decades, from the Spanish Civil War to World II. The surrealists believed in the power of the subconscious, in the hidden meanings of life which existed outside of the material world. “So strong is the belief in life, in what is most fragile in life—real life, I mean—that in the end this belief is lost,” wrote André Breton, leader of the surrealist movement.

The fragility of life is at the heart of those occurrences we deem surreal. Perhaps nothing encapsulates that more in recent memory than the COVID-19 pandemic. To suddenly find that even the most mundane spaces—grocery stores, subway cars, offices, a friend’s home—are rife with danger is an experience that seems like a bad dream. That vibrant cities could shut down overnight or that our government could let more than half a million people die from a virus all seem “surreal” in the truest sense of the word.

Whether world war or a global pandemic, these periods of history can feel nightmarish, especially given the bedrocks of American belief. Much of our national identity stems from our belief in meritocracy: that if we work hard, we will be rewarded. In a nation that values optimism, practicality, and planning, it’s difficult to cope with the suddenness of trauma: the fact that some questions cannot be fully answered. It’s why we struggle to mourn, to sit with our suffering and to see it as real, to be awake with pain and not to understand it as “the irrational reality of a dream.”

Whether in 2021 or 1921, we have tended to respond to uncertainty in much the same way we always have: with a desire for clarity, for absolute truths. The craving for definition has not gone away, even if the market for print dictionaries wanes.

Nearly two centuries after the first publication of Webster’s dictionary, Americans turn to this book when they feel confused, afraid or destabilized. And the dictionary continues to serve a vital purpose in times of tumult. “If the entire country is looking up a word…implicitly the country is asking us a question,” Sokolowski said. “And what is the dictionary for but to answer questions about language?”

Adapted from AMERICANON: An Unexpected U.S. History in Thirteen Bestselling Books by Jess McHugh published by Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com