It was around 4 a.m. on April 28 when Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas jolted himself awake. As he lay in the dark, his mind locked onto the decision he had made the day before to limit the Trump-era practice of arresting and deporting undocumented immigrants who show up at local courthouses for legal proceedings.

Unable to sleep, he got out of bed, fired off an email about the politically sensitive move and then turned to the next conundrum. In the dark, he scanned the most recent data on how long unaccompanied minors were spending in Border Patrol custody, one of several onerous issues awaiting him in the day ahead. “There are times when I try to go back to bed, and there are times when I realize it’s not going to work,” Mayorkas says 3½ hours later over the engine noise of a Coast Guard Gulfstream jet, heading from Washington, D.C., to New York City’s La Guardia airport for a day of meetings. “This morning it wasn’t going to work.”

A veteran federal prosecutor and top immigration official, Mayorkas has handled ethically fraught law-enforcement issues for most of his adult life. But this is a new kind of pressure. He inherited the mess left by the Trump Administration’s anti-immigrant crusade: an estimated 1,000 children still separated from their families, 395,000 refugees waiting for word on their asylum requests, and a massive backlog of 1 million citizenship applications unprocessed. At the same time, he faces a surge of new border crossers—the number of migrants trying to come to the U.S. has increased over 70% since President Biden took office and has reached a two-decade high. Then there’s the continued business of enforcing the law, whether by cracking down on illegal immigration or deporting convicted criminals who’ve managed to slip in.

Immigration is just one of the difficult topics under his remit. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was created after 9/11 by consolidating 22 federal agencies to prevent another terrorist attack, and running that conglomerate of bureaucracies has proved infamously unwieldy ever since. The third largest department in the federal government is charged with keeping bombs off planes, patrolling America’s waterways, staffing border checkpoints, protecting the President, responding to natural disasters, ensuring U.S. elections aren’t hacked and helping businesses defend against cyberattacks like the one on May 7 that temporarily shut down a pipeline that provides 45% of the East Coast’s fuel. Doing all that amid the pandemic and the aftermath of the deadly Jan. 6 insurrection at the Capitol “is going to be an awful lot like juggling flaming torches,” says Michael Chertoff, who headed the department from 2005 to 2009 under George W. Bush and supports Mayorkas’ moves so far.

Biden’s opponents aren’t making it any easier. The Administration’s current approach “sends a message to Central Americans that you can get in,” says Mark Krikorian, head of the Center for Immigration Studies, a think tank that pushes for reducing legal immigration. Describing that as humane, as the Administration has, is “tendentious,” Krikorian says. Polling suggests it’s a hard issue for the Biden team, with more than half of Americans disapproving of his handling of the influx of migrants at the border. Republican strategists have been quick to capitalize on that, and GOP lawmakers travel to the border to draw attention to the issue.

Mayorkas’ backers see him as the best candidate to help Biden achieve his goal of managing a broken immigration system through a mix of empathy and law enforcement. Mayorkas is the first immigrant and Latino to head the department and brings his lived experience as a Cuban refugee and son of a Holocaust survivor to the rollback of Donald Trump’s most controversial policies. But DHS is still a law-enforcement agency at its core, and Biden picked him not for his personal history but because of his reputation for being a tough prosecutor, a senior White House official and a former top transition adviser tell TIME. How Mayorkas strikes the balance will define much about how the world sees America, and America sees itself, in the post-Trump moment.

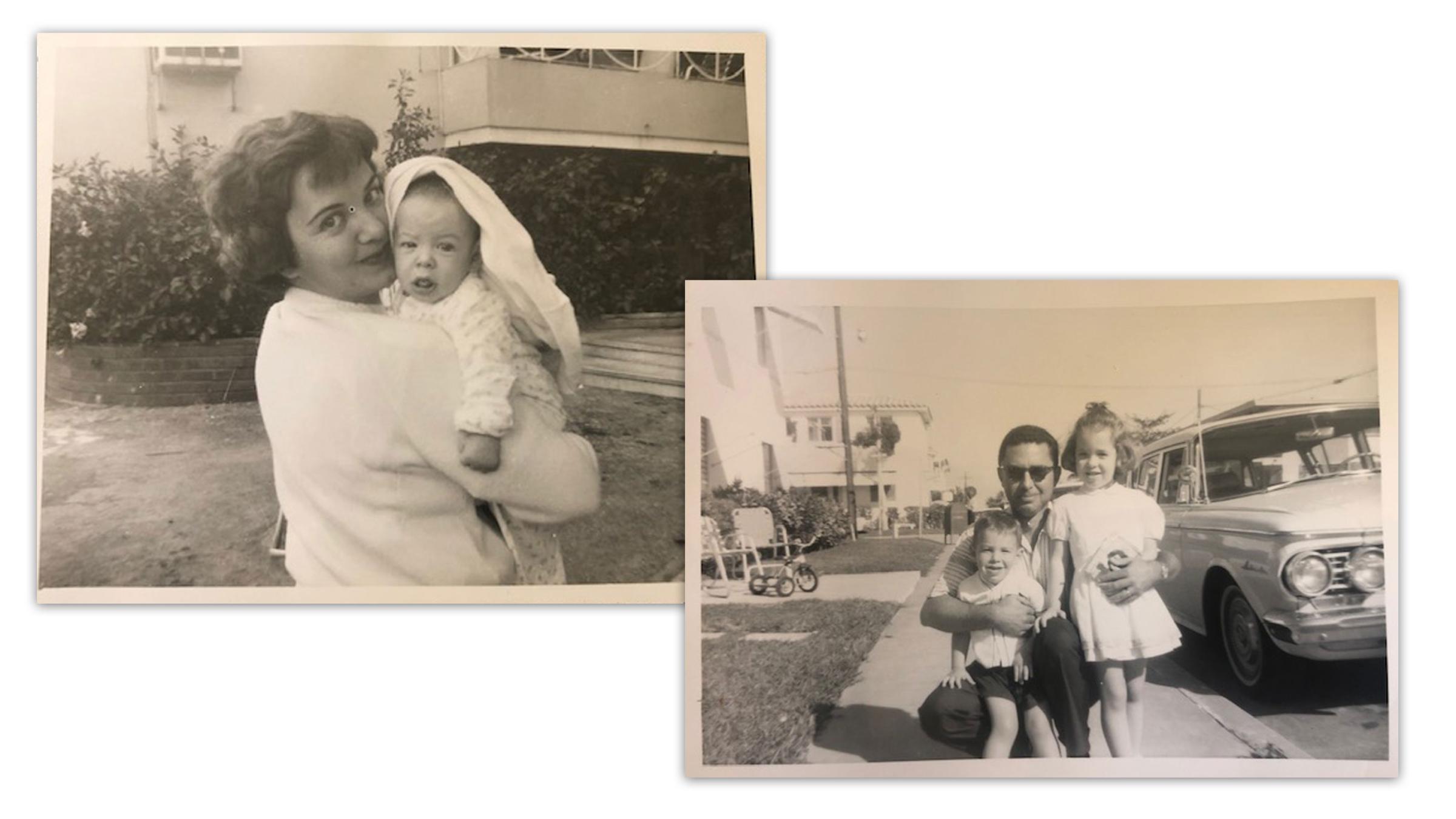

After the jet lands at La Guardia, Mayorkas gets into a waiting SUV and heads across town to Lincoln Center, where 39 people from 21 different countries are waiting to take their oaths to become new U.S. citizens. For Mayorkas, presiding over naturalization ceremonies like this one is personal. Born in Havana less than a year after Fidel Castro’s communist takeover, Mayorkas was already a refugee by his first birthday. His father Charles, a gregarious Cuban whose parents were Turkish and Polish transplants, owned a steel-wool factory and expected to lose it in Castro’s imminent nationalization of businesses. On Aug. 21, 1960, he and his wife Anita took a Pan American Airlines flight to Miami with 9-month-old Ali, as he’s known by friends and colleagues, and his 3-year-old sister Cathy, part of a wave of nearly 250,000 Cubans who sought shelter in the U.S. from 1959 to 1962.

For Mayorkas’ mother, it was her second time becoming a refugee. As fascism spread through Europe in the late 1930s, Anita and her parents escaped Romania for southern France. With Vichy France collaborating with the Nazis, they were blocked from escaping to the U.S. The family does not know the exact details, but at that time visas were hard to come by and immigrants had to prove they had enough money not to become a “public charge,” or financial drain on the government. Anita and her parents sailed to Cuba on one of the last ships that escaping Jews were allowed to board, leaving France in 1941. The Nazis murdered her grandparents and several uncles left behind in Europe.

From Cuba, Mayorkas’ family eventually settled in Beverly Hills, Calif., where their lives were not particularly glamorous. Mayorkas’ father was a workaholic, says his sister Cathy, getting up at an “ungodly hour” to work at home before his job as a comptroller at a textile business, then staying up late to do the same. His mother, who spoke precise English in a lilting Romanian accent, became a teacher. Mayorkas graduated from Beverly Hills High School in 1977 and UC Berkeley in 1981 before earning his degree at Loyola Law School in 1985. After law school, he was drawn to public service as a prosecutor in the U.S. Attorney’s office in Los Angeles. “It was an ethic instilled in me by my parents,” Mayorkas tells TIME during an interview at DHS headquarters across the Anacostia River from the Capitol. “And also, quite frankly, my family’s life history drove me to that.”

Mayorkas’ ascent has not been without controversy. After President Obama nominated him to lead the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) in 2009, whistle-blowers inside the agency alleged that he had fast-tracked visas for projects associated with former Senate majority leader Harry Reid, former Virginia governor Terry McAuliffe and Hillary Clinton’s brother Tony Rodham. In 2015 the department’s inspector general found no explicit evidence of wrongdoing but said Mayorkas’ actions “created an appearance of favoritism and special access.” Mayorkas denied the allegations. In February, he was confirmed as Secretary on a 56-43 Senate vote, one of the closest of Biden’s Cabinet.

As he made his way across town in his SUV to the naturalization ceremony, Mayorkas revisited some of the hard calls he has made over the years. He described the politically risky decision to cut $160 million from the operation costs of the immigration service in 2010 to help avoid raising citizenship application fees from $680 to $727, the thinness of an immigrant family’s budget a visceral memory of his own youth. Arriving minutes later at Lincoln Center, he walked across the plaza into a small auditorium, where he strikes up conversations with several dozen immigrants about to become citizens. “You will find, if you have not already, that this is indeed a country of tremendous opportunity,” Mayorkas says, but “sometimes we do not live up to our highest ideals.”

When Mayorkas moved into his office at DHS headquarters in early February, he placed a photo of his dad on his desk, frozen in the middle of an uproarious laugh at an outdoor party, a jubilant mood he never remembers seeing in his father when he was growing up. “He worked so unbelievably hard,” Mayorkas says. He also stood on principle. “He was just straight to a fault,” Mayorkas says. “I remember my mom saying, ‘Do you have to tell your boss you don’t like his idea, every time you don’t like his idea?’”

One of Mayorkas’ first law-and-order steps has been getting his own house in order. In March, he dismissed the department’s entire advisory council, concluding that some of its members were there to advance political agendas rather than offer policy expertise. He followed Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s lead in launching an internal investigation into domestic extremism within his own department. Other than reading about reports of social media profiles, he says, he has “no greater information” than what’s in the public domain about this threat, but he says he has an obligation to “ensure that we do not have violent extremists within our ranks.” On May 11, the department announced it was forming a Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships to further target domestic extremism.

Mayorkas’ inclination toward enforcement is showing up in some of his policy decisions as well. After Lincoln Center, his next stop was a 1½-hour meeting with a dozen or so immigration attorneys and community leaders about how he can improve the treatment of people facing deportation. Mayorkas has asked for a complete overhaul of the guidelines used by Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers to determine whom to arrest and whom to deport. Several activists argued forcefully that immigration agents shouldn’t consider criminal convictions when deciding whom to deport, given the stark racial disparities in American policing.

Mayorkas listened to the advice but afterward remained skeptical of the calls for a blanket pass on criminal histories. “I have a fundamental disagreement with some of their idealism,” Mayorkas says of the advocates pushing for a broader overhaul. “They are talking about a system that is not grounded in the law.” One individual, whose deportation case he recently reviewed, entered the U.S. illegally as an adult and has multiple felony sex-offense convictions. Not to deport that person, Mayorkas says, “would be a complete abdication.”

If some dislike his prosecutor’s instincts, however, others are more concerned about his humanitarian streak. One of the first Trump-era rules Mayorkas revoked was the “public-charge rule.” Like the restrictions that had kept so many refugees like his mother out of the country during the Holocaust, this rule linked immigration status with financial self-sufficiency. He has reunited at least four families separated at the border under Trump, though he declines to say when the rest of the 1,000 will be reunited. Breaking with the previous Administration’s default position that keeping refugees out of the country was better for national security, he designated both Venezuelans and Burmese for temporary protected status. Mayorkas told TIME he was always in favor of allowing in up to 62,500 refugees, even when the White House initially kept the Trump-era level of 15,000, before raising it on May 3.

The hardest balancing act has been at the U.S.-Mexico border. Biden announced shortly after taking office that unlike Trump, he would not expel children who arrived alone. But legally, unaccompanied minors can remain in federal detention facilities for only up to 72 hours before being transferred to the care of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), where officials unite them with sponsors—usually relatives or foster families—while their cases are adjudicated. After Mayorkas was confirmed, he started to hear concerns from his staff that the border detention facilities were beyond capacity. Children were staying longer than 72 hours, and HHS’s promises to find additional beds in outside shelters had not materialized.

On a trip to the Rio Grande Valley on March 6, Mayorkas concluded that HHS needed help and, pressed by Biden in an Oval Office meeting four days later, promised to speed up the system. Within a week, he had directed FEMA to set up over a dozen emergency shelters for HHS that could house up to thousands of children. He deployed over 300 immigration staff to assist HHS with virtual case management to unite children with their sponsors and activated DHS’s volunteer force to help children in shelters.

But by late March, images leaked of children lying on mattresses on the floor under blankets resembling tinfoil in detention centers, causing an outcry. Immigration advocates lamented the crowded, appalling conditions. Republican critics alleged that the Biden Administration’s decision to allow minors to stay in the U.S. had caused more children to come and that the White House was unprepared to deal with it.

Mayorkas’ allies say it would have been much worse without the steps he took. The number of unaccompanied migrant children crossing the border decreased by 12% from March to April, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) figures show. The number of children in Border Patrol detention facilities has also decreased from 5,700 at the end of March to under 800 as of May 6, according to Administration officials, and these children now spend approximately 24 hours there on average, down from 139 at the beginning of April. “If it weren’t for him driving this, we would still be looking at lines of kids in Border Patrol custody, in HHS custody,” a White House official says.

Mayorkas admits these are temporary solutions that don’t tackle the under-lying problems. Even some Biden allies on the Hill are critical. “Trump overdid it, separating kids from families,” says Representative Henry Cuellar, a Democrat who represents parts of the Rio Grande Valley. “They’re trying to be humane at the border, but the pendulum has swung too much from the crazy stuff Trump did to another one where being humane means ‘Let’s not enforce the law in many ways.’” (DHS officials say they are following the law.)

Republicans are even more critical, alleging that Mayorkas’ systematic roll-back of Trump’s policies incentivizes illegal immigration, saying it both endangers migrants who have paid huge fees to smugglers to make the dangerous trek and compromises national security by allowing criminals to slip in. Earlier this year, CBP apprehended two Yemeni men crossing the border whose names appeared on a federal terrorism watchlist. Indiana Senator Todd Young, the top Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Counterterrorism, has repeatedly prodded Mayorkas for more information about the threat posed by illegal entries that he says Mayorkas hasn’t provided. “Incidents like this remind us that a functionally open border poses a national security threat to the United States,” Young wrote to Mayorkas in May.

Just after 2 p.m. on Mayorkas’ day in New York, the Homeland Security Secretary decided it was time for lunch. The skyscrapers of Manhattan fell back as his black SUV drove across the Williamsburg Bridge to a popular Venezuelan arepas bar on Grand Street in Brooklyn. Tucking into a takeout box of green plantains, rice and seared tilapia, Mayorkas spoke of his parents. If his dad was stoic, his mother was relentlessly positive—an “incredibly optimistic person,” his sister says, despite her family’s loss in the Holocaust. “My mom,” Mayorkas says, “given what she went through, was ‘Every day is a new one, something beautiful can happen, something tragic can happen, but every day is a new life, and therefore we have an obligation to be better today than we were yesterday and tomorrow than we are today.’ That was her.”

Mayorkas keeps a photo of her near the one of his jubilant, laughing father, at his desk in Anacostia, a reminder of her values. As he talks through the hard calls ahead, Mayorkas says that in the end, his mother’s philosophy is more deeply ingrained in how he wants to see the world—and run DHS. “I would tell people around the leadership table, ‘I am more of my mother’s son in that regard than my father’s,’” he says.

—With reporting by Mariah Espada/Washington

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Alana Abramson at Alana.Abramson@time.com