Many academics don’t get much popular attention for their work, and historian Olivette Otele knows it. The Paris-raised, U.K.-based scholar was surprised to see her research draw widespread attention over the last year—but, given the global context into which her latest book arrived, perhaps she should not have been so shocked.

“I was very flattered that people think that what I do is not just staying in an ivory tower,” she says. “It has resonance for everybody.”

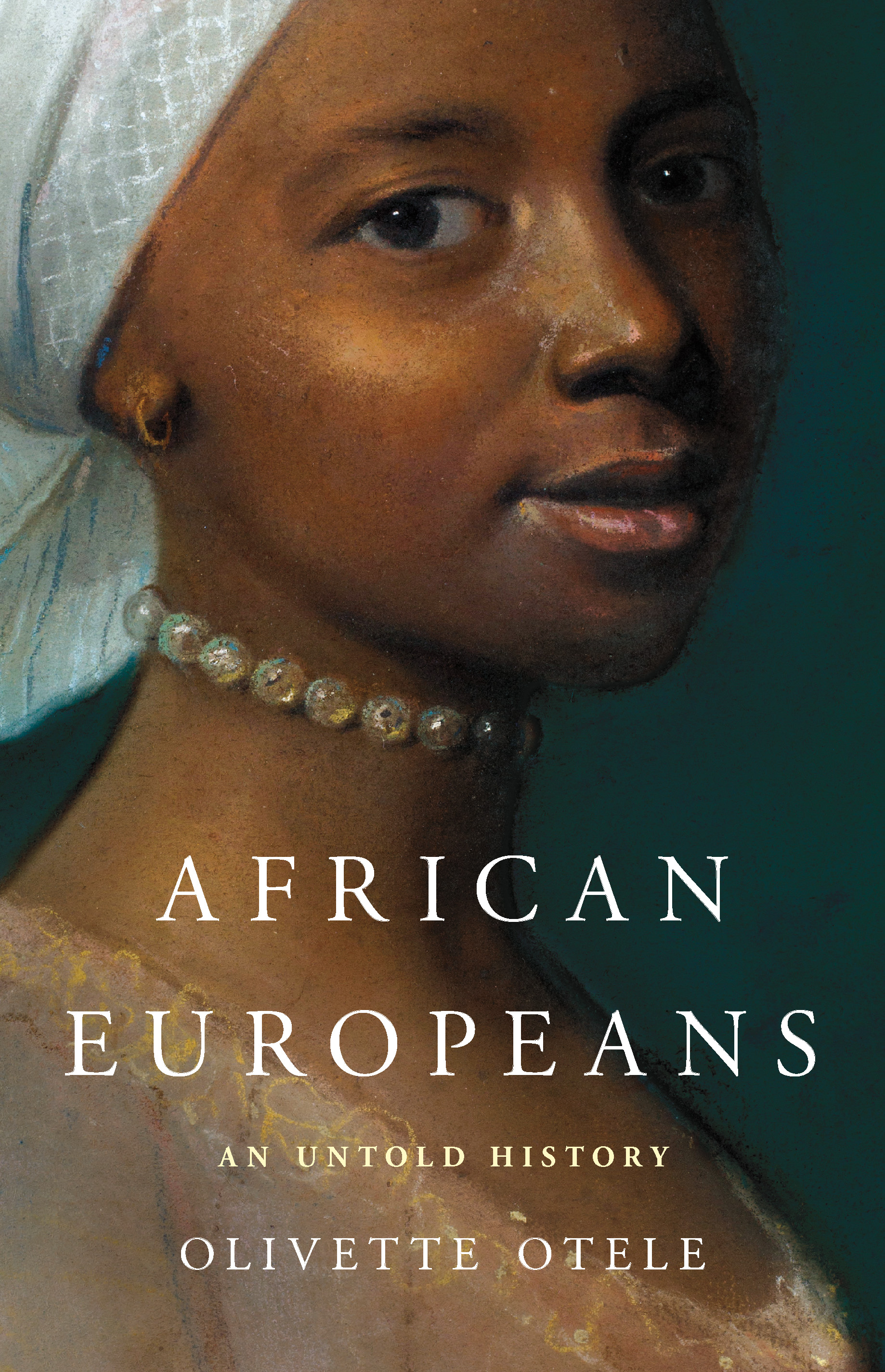

African Europeans: An Untold History, which was published in the U.K. in October and in the U.S. on Tuesday, traces the presence of people of African descent in Europe from as early as the era of the Roman Empire up to the present day. In the U.K., the book has been long-listed for the prestigious Orwell Prize for Political Writing, and received positive reviews from readers and academics alike. Otele, an expert on the history of colonialism and slavery, starts by looking at early encounters between Africans and Europeans, detailing the ways the ancient women warrior queens known as the Candaces fiercely protected their kingdoms in Ethiopia to resist the rule of the Roman Empire, dating as far back as 23 BCE. Through exploring these histories, Otele wanted to upend assumptions and shed light on the wider connections between African European people and mainstream ideas about what European history looks like.

“For many people in the global north, Ancient Rome and Ancient Greece are seen as the birthplaces of civilization,” she says. “Well, the world was much more multicultural than we thought it was.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Standing on their shoulders

Otele is pioneering in her own right: in 2018, she became the first Black woman in the U.K. to become a history professor. She is currently based at the University of Bristol in south west England, and is the vice-chair of the Royal Historical Society. A study last year found that less than 1% of professors employed at British universities are Black, and few British universities employ more than one or two Black professors.

Writing the book, she says, reinforced her belief in the fallacy of the “self-made man” — “I would never have done it on my own,” she says. That’s why she’s committed to telling the often overlooked and erased stories on which today’s world is founded, especially the stories of Black women and their experiences of empire, colonialism and slavery. “When you talk about colonial history, you think about the fight between men….But what about Black women who were mothers and daughters, and who were used as reproductive tools? I’m a Black woman. I can’t separate ‘Black’ and ‘woman’.”

Some of the hidden stories in the book may be better known than others. For example, born in 1510, Alessandro de Medici was the first Medici duke of Florence, and his mother is believed to have been a free African woman, challenging assumptions about what 16th century Renaissance aristocrats may have looked like. During his lifetime and beyond, writing and artistic depictions of de Medici focused on his African heritage, and Otele points out that this was seen in a negative light; in his later life, he acquired a reputation as a despot and a tyrannical ruler driven by lust and desire for debauchery.

“I’m literally in love with every single character even when they’re not particularly nice,” says Otele. “These are real people, and you can very much connect with them. I really see the links between the present and the past: these are stories that resonate, they’re about discrimination, about resilience, about success.”

One of these is the Senegalese-born boxer Louis M’barick Fall, better known as “Battling Siki.” He was thought to have been chosen as a child by a European benefactor who paid for his passage to France, and was declared the world heavyweight boxing champion in 1922. Otele writes that Siki’s story reflects the strength of other African Europeans who managed to survive and thrive in societies that often despised them. To tell Siki’s story, Otele traveled to his home community in Senegal, where she tried to locate his birthplace.

But that ability to thrive wasn’t limited to more famous characters like de Medici and Siki. It can also be seen in the stories of dual-heritage women from the Ga ethnic group in Ghana in the 18th and 19th centuries, and in the work of scholars like Gloria Wekker, an Afro-Dutch scholar born in Suriname, which gained independence from the Dutch in 1975. “I really wanted people to understand that each one of us is standing on the shoulders of our forebears,” says Otele. “it’s about not forgetting those who were not the big figures of history.”

‘We are completely immersed in the legacies of the past’

For Otele, the present is informed by these stories of resilience from the past. “With the Black Lives Matter movement, we’ve reconnected with some of those stories, but I wanted people to think not just globally but across a longer time and period,” she says. “Learning about these stories gives you hope.”

One focus of Otele’s work in African Europeans and beyond is the way in which colonial histories are erased or misrepresented in the present. Earlier this month, the British government was widely condemned and criticized for a report it commissioned on race in the U.K.; the report had called Britain a “model for other white-majority countries,” with the report’s chair writing that “we no longer see a Britain where the system is deliberately rigged against ethnic minorities.” A U.N. panel called the report “a tone-deaf attempt at rejecting the lived realities of people of African descent and other ethnic minorities” in Britain. Additionally, a recent investigation found that Black and Asian soldiers who died fighting for the British Empire were not commemorated formally in the same way as their white comrades because of decisions underpinned by “pervasive racism of contemporary imperial attitudes.”

“We are completely immersed in the legacies of the past,” says Otele. “You have to remember that what we are living today, the brutality and the systemic racism, all this was built over time and carefully crafted. Some people don’t understand where it’s coming from, some people don’t want to understand because it’s created the hierarchy that suits the vast majority of people [in Europe].”

But the historian is hopeful that the world is at a point of progress, even if it seems that efforts to interrogate and examine Britain’s past fairly are facing backlash.

“Part of me, like everybody else, is angry. But if you take a step back, things are changing. For centuries, there was an accepted narrative based on amnesia and erasure, that equates to violence, because the stories of some communities were completely diminished,” she says. Now, with more dialogue about these histories, she sees a greater understanding that a single narrative about national identity is not necessarily what suits everybody. “There’s a pushback on both sides, and that is a sign for me of progress, because that’s exactly how memory building a collective memory works—it’s work of contention, and it’s not pretty.”

As her book hits U.S. shores, she hope it will help show that while the American story is unique some ways, the country’s experience with racism and discrimination is part of a global history. Otele writes about 18th century France, when authorities set up the Police des Noirs, or “police for Black people,” with the express aim of limiting the number of Black people in the country. That history of violence entrenched in racist attitudes has links to the police brutality we see in other parts of the world, including the U.S., today, she says.

That’s part of why Otele sees her book’s title—African Europeans—as a “call to arms.” History shows that those two identities are not as separate as many people may think.

“I’m hoping it will make people understand that there’s power in community, in collaboration across communities,” she says. “There’s so much power when we unite.”

Correction, May 6.

The original version of this story misstated African Europeans’ relationship to the Orwell Prize for Political Writing. It was long-listed for the prize, not shortlisted.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com