A small bipartisan group of lawmakers in Washington are making an urgent push to get a police reform bill passed in Congress in the wake of a Minneapolis jury finding Derek Chauvin, a white former police officer, guilty of murdering George Floyd, a Black man, last May.

Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle say they are optimistic that renewed bipartisan talks will result in a deal that can pass both of the closely split chambers of Congress. President Joe Biden has given lawmakers a deadline to get it done by the anniversary of Floyd’s death on May 25. “Congress should act,” said Biden during his joint address on Wednesday. “We have a giant opportunity to bend the arc of the moral universe toward justice.”

The way forward in reforming America’s police force must now be found in a legislative body regularly paralyzed by partisanship and disagreement, on an issue that has become so divisive that compromise can translate to losing support from members on either side.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. In the wake of multiple killings of unarmed Black men and women at the hands of police in recent years—including Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Daunte Wright, Elijah McClain, and Eric Garner—and months-long protests calling for racial justice that broke out across the nation after Floyd’s death, members of Congress are desperate to find solutions that can help prevent future acts of police brutality and excessive force. The day before Chauvin was found guilty of second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter, a California man, Mario Gonzalez, reportedly died after officers pinned him to the ground for several minutes. The day the Chauvin verdict was announced, Ma’Khia Bryant, a Black teenage girl, was shot dead by police in Ohio.

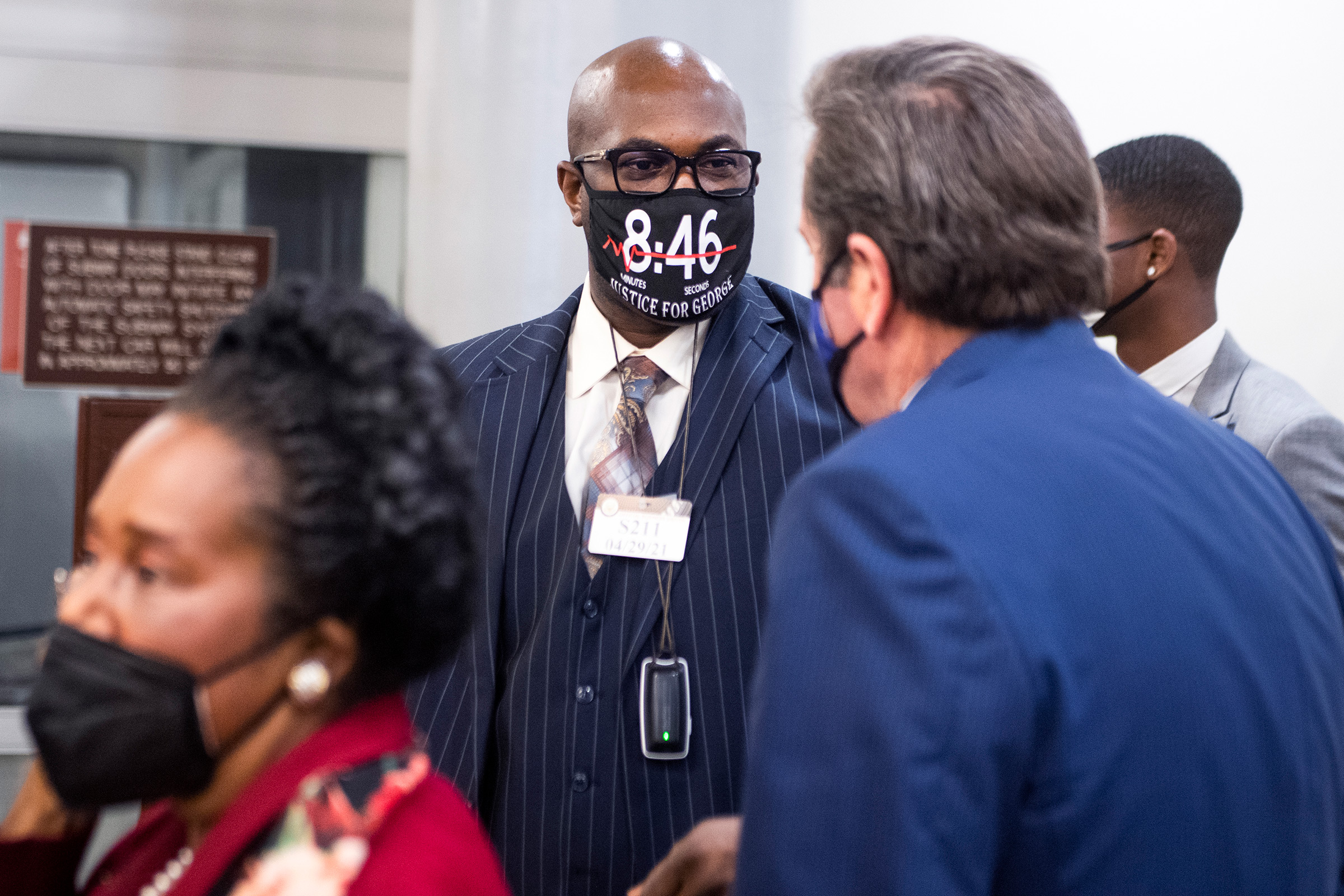

Three lawmakers are guiding the conversations to strike a deal on a new law. Rep. Karen Bass, the California Democrat who introduced the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act that has passed in the House twice but not advanced to the Senate, is taking lead among Democrats in the lower chamber. In the Senate, New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, a Democrat, and South Carolina Sen. Tim Scott, the sole Black GOP Senator, are leading negotiations. The talks have involved Philonise Floyd, George Floyd’s brother, and other relatives of individuals who died from police violence. Speaker Nancy Pelosi has also been briefed by Bass on the talks’ developments, and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer told reporters he’s spoken with Booker.

But details of who might be willing to get on board with a compromise—or what that compromise could look like—remain murky as the team navigates the delicate task of bringing lawmakers together.

“One slip of the tongue could ruin things, and we don’t want something with so much potential to go down the drain because we weren’t thinking through everything we’re doing and saying,” says a Democratic staffer with awareness of the negotiations, who was granted anonymity to speak candidly about where the conversations stand. “We’re trying to be very careful with… how we roll it out, what’s included, [and] how we brief people beforehand.”

Lawmakers leading the talks are reluctant to discuss the potential bill’s details or bipartisan support. Asked by TIME on Tuesday which Republican lawmakers he might convince to support a bipartisan police reform bill, Scott declined to name any names in fear of stalling progress. “That might prevent me from getting them on board,” he says. “My theory is, if you want to get something done, you try to get it done before you talk about how you get it done or who you get it done with.”

Booker also skirted questions on which police reform ideas—like bans on no-knock warrants and police chokeholds—were being discussed by the group and who the group was involving in the talks. “There are a lot of really substantive conversations going on and I would rather not characterize them,” he told TIME Tuesday.

“I think that we are making progress, and I’m really encouraged,” Booker told reporters on Thursday. “As I’ve been saying from the beginning, Tim [Scott] is an honest broker, and we’re trying to make it work.”

‘There’s a lack of courage’

The failed police reform bills Democrats and Republicans proffered in 2020 offer some clues on what the respective parties are hoping to negotiate this time around.

The Democrats’ George Floyd Justice in Policing Act was wide-reaching: banning no-knock warrants for drug cases, which played a role in the death of Breonna Taylor; creating a national registry to track police misconduct, which would prevent police officers with histories of disciplinary action and termination from being hired at different departments; incentivizing state and local police agencies to limit chokeholds; restricting transfers of controlled military equipment from the Department of Defense to local police agencies; and providing the Department of Justice (DOJ) the power to subpoena local police agencies. The proposed legislation also reduced legal protection of officers through qualified immunity, the legal doctrine that prevents government officials including police officers from being held personally liable for constitutional violations while on the job.

The Republicans’ Justice Act, which was introduced in the Senate by Scott after Floyd’s death but didn’t meet the required 60 votes to advance, was narrower. It requested state and local police collect data on no-knock warrants, increased funding for more body cameras, and required state and local governments to report use of force to the DOJ. Like the Democrat’s version, it also incentivized banning chokeholds among state and local police agencies.

Notably, it did not include any changes to qualified immunity, so far a major sticking point in the negotiations that are underway. During last year’s civil unrest, former President Donald Trump touted the GOP as the “party of law and order,” a mantle that many party lawmakers have perpetuated in his absence. Weakening qualified immunity, they argue, would impede police officers’ ability to do their job. “It’s an incredibly dangerous job, there are all kinds of risks associated with it,” Senator Josh Hawley said at the Capitol complex on Tuesday. “I think that police would feel very vulnerable and legally exposed if they didn’t know they had at least this qualified immunity backdrop that provides some protection for them to go out there in those dangerous situations and make decisions on the spur of the moment.”

Some progressive Democrats say that failing to diminish the strength of the doctrine would be failing to meet the urgency of this moment in the fight for racial justice. “The abolition of qualified immunity, which is code for impunity, is the central provision of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act. It should be non negotiable,” says Rep. Ritchie Torres, a New York Democrat and member of the Congressional Black Caucus. “I thought Republicans believed in individual responsibility. Police officers should be held individually responsible for misconduct.”

Democrats will need the unified support of their own ranks as well as 10 Republicans to pass any new police reform legislation in the Senate. Those votes are going to be difficult to get; it isn’t yet clear all Democrats would be on board. Sen. Joe Manchin, a West Virginia Democrat who yields enormous power in the evenly divided Senate for being a centrist, says that component is important to him in considering a new police reform bill. Qualified immunity “is something that all of the policemen in my state are very much concerned about,” he says, adding that diminishing this legal protection could hurt police departments’ ability to recruit new officers. “We want to make sure there is a balanced approach—whatever might be recommended,” he says, “so I’m watching it very carefully.”

Even as they tiptoe around the sensitive negotiations, Scott didn’t shy away from taking a shot at Democrats on Wednesday, when he accused them of filibustering his police reform bill last year because they “seemed to want the issue more than they wanted a solution” during his GOP rebuttal to Biden’s joint address. “But I’m still working. I’m hopeful that this will be different,” he added.

If they can work out the qualified immunity component, there may be other provisions that could threaten to derail a bill’s passage if enough members take exception to them. Whatever the final product may look like, it’s almost certainly going to leave many lawmakers feeling their priorities were unsatisfied. And when that might happen is still nebulous. Asked for an update on the talks after his GOP response, Scott told reporters that they would not be announcing anything on police reform until “after the break.” (The House returns for votes in mid May, and the Senate is scheduled to be in recess next week.)

On Thursday morning at a press conference, Speaker Nancy Pelosi also avoided committing to a timeframe after Biden’s fresh deadline. “We will bring it to the floor when we are ready, and we’ll be ready when we have a good strong bipartisan bill,” she said. Booker also refused to commit to a timeline, telling reporters that he wants to get this done “as quickly as possible” and that he was focusing on the “urgency of the work.”

In the meantime, activists and other stakeholders are keeping close tabs on lawmakers’ progress. Amara Enyia, the policy and research coordinator for the group Movement for Black Lives, says the Democrats’ George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which included the provision on decreasing qualified immunity protections, was already insufficient to address the root problems of racism in the criminal justice system. A further watered-down version of that bill wouldn’t come close to solving America’s problems with policing, she says.

“There’s a lack of courage,” Enyia says of the earlier bills and the attempts to solidify a bipartisan version of them. “This legislation is sort of doing what is comfortable. It’s the unwillingness to stretch your imagination beyond what we’ve always done. And so they’re falling back on the same proposals that have been put forth, year after year after year.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Abby Vesoulis at abby.vesoulis@time.com and Lissandra Villa at lissandra.villa@time.com