It’s evening in Arkansas and Joanna Brandt has just closed down her shop, a funky boutique with locally homemade salsa sold next to vintage glassware and embroidered pillows. Next on the to-do list: yet another news interview with her son, Dylan, a 15-year-old with a thatch of floppy blonde hair and piercing eyes. The Brandts are tired. It’s not because of the pandemic; Joanna has actually enjoyed remote-schooling her two kids, and the shop has done a decent online and pick-up business. And it’s not the management of Dylan’s medical treatments, weekly hormone therapy injections he has learned to administer himself over the past eight months. No, they—and the rest of Arkansas’ trans community and its advocates—are tired because this spring, their state has been systematically stripping trans youth like Dylan of their rights. And this week, with one more bill passing the state legislature, Dylan’s access to hormones has been placed in jeopardy. “With this one bill, they took away so much,” he says. “The one thing that is helping me become who I want to be and has made me as happy as I am and as confident as I am: they’re taking that away, without a second thought.”

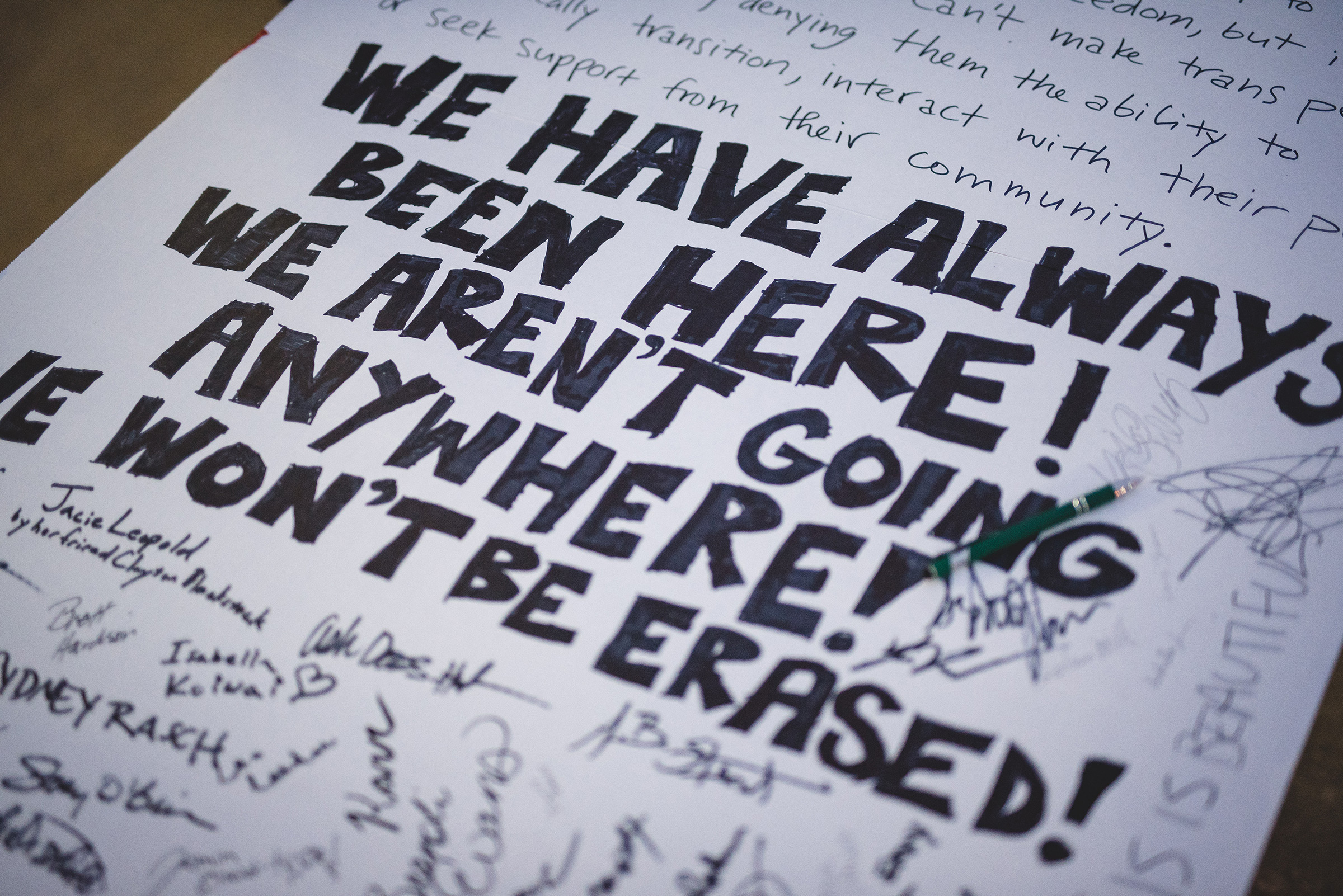

On the afternoon of April 6, the Arkansas state legislature passed HB 1570, the first bill in the U.S. that effectively bans trans youth from transitioning. Specifically, it bans gender-affirming care for trans youth, making it illegal for clinicians to provide puberty blockers and hormone therapy. This is the third anti-trans bill passed this spring in Arkansas, one of over a dozen states with anti-trans legislation currently in contention; nearly 100 anti-trans bills are being considered in state legislative sessions according to the Human Rights Campaign, the highest number of any year on record. The bills differ: some would ban trans women and girls from competing on sports teams consistent with their gender identity; some would restrict opportunities for medical care; some would give care providers the right to deny a trans patient treatment based on moral or religious grounds. But they share a common theme: their attempts to limit and minimize the potential for trans youth to live normal lives, and their backing by conservative groups seeking a new hot-button issue around which to rally. The ACLU, meanwhile, plans to sue the state of Arkansas.

The CDC’s last Youth Risk Behavior Survey, released in 2019, estimated about 2 percent of U.S. high schoolers identify as trans—a proportion that equates to roughly 300,000 teens across the country, and doesn’t count students not enrolled in high school, or those unsure of their gender identity. Thirty-five percent of surveyed trans students attempted suicide in the prior year. And Arkansas is also one of three states in the U.S. that does not have a comprehensive hate crime law, compounding the threats that trans people face. Now, the trans communities these bills impact are doing their best to fight, with limited resources, and keep hope alive. For trans youth like Dylan, it’s another roadblock in his attempts to simply be Dylan.

The trans community mourns

“There’s a panic,” says x Freelon, 22, over the phone from Little Rock, “and there’s been rising desperation.” Freelon—who identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them pronouns—is the Executive Director of Lucie’s Place, a homeless shelter and resource center for LGBTQ+ young adults. Freelon has only been in their role for a little under a year, but already they’ve noticed a significant uptick in the calls and emails flooding their accounts; over 100 people a week, they say, are now reaching out for help. The legislation will embolden those who reject trans and queer lives, Freelon says, whether it’s through insidious things like making housing unavailable or more overt violence. Trans youth and young adults are coming to Lucie’s Place considering dropping out of school, or hoping they can continue learning remotely to maintain their safety from government-controlled spaces.

And then there are the fears about suicide attempts. Statistically, trans youth are at higher risk of suicide; anecdotally, organizers like Freelon and Willow Breshears, an 18-year-old community organizer at Little Rock’s Center for Artistic Revolution and the founder of the Young Transwomen’s Project, are already concerned. “I heard from the mom of a trans kid that if this bill passed, that her child was going to kill themselves,” says Breshears, who is trans herself. “That was really difficult to hear. But that’s the reality, the kind of environment that we live in in Arkansas.”

Kristofer Eckelhoff, a trans voice coach, knows how damaging this kind of environment can be: he grew up in Arkansas as part of a Southern Baptist community, and came to his gender identity at 31, after struggling through four years of forced conversion treatments which he says led him to addiction and a suicide attempt. He has since recovered and moved to New York City, but when we speak over Zoom, he is back home helping care for his mother. During our conversation, HB 1570 is officially passed. “It’s heartbreaking,” Eckelhoff says. “I just really hope the legislature comes to their senses and ends it, because it’s going to kill people.”

Trans youth also face increased incidences of homelessness; in general, LGBTQ+ youth make up as much as 40 percent of the 1.6 million homeless youth in the country. “They’re being sent the impression that their lives don’t matter, but they’re also to be made a public spectacle, and that they’re somehow deserving of these levels of harassment and investigation into their existence,” Freelon says.

The prevailing sentiment is grief. “There’s a lot of mourning of trans youth who are not even born or have not even been provided the space to become trans,” says Freelon. It’s a feeling that Dylan Brandt and Breshears share. And while Breshears, who came out at 13, is grateful she’s already 18 and able to make her own choices independent of the new ban, families like the Brandts don’t even want to consider what Joanna calls Plan B: saying goodbye to her shop and her home, and uprooting her family to somewhere that treatment is available to her son. If it comes to that, though, they likely won’t be alone. “I’ve heard from a lot of trans parents that they are actually going to be moving out of state because of this bill,” Breshears says. The bill will go into effect in July, and most families are hoping that the ACLU’s suit might stall it further. But the future is uncertain.

Pain and persistence

For a few days early in April, it was not all bad news. Republican Gov. Asa Hutchinson vetoed HB 1570 on the grounds that the government would be overstepping in its involvement in physician and family decisions. The evening after his decision, Chase Strangio—a nationally-recognized trans advocate and the deputy director for transgender justice at the ACLU—and Dr. Karen Tang, a gynecological surgeon, went live on Instagram to discuss the surprising outcome. “Today, obviously, was exciting,” Strangio started off by saying, nodding to Hutchinson’s surprising veto. They discussed the misinformation that was circulating around what gender-affirmation care for minors really looks like: puberty blockers, mostly. “Most gender affirmation care in minors is not surgical; it’s medical,” Dr. Tang explained. That can include options like counseling and treatments like puberty suppressants, which give a child time to “explore and confirm ideas of gender identity,” and allow puberty changes to continue if treatment is stopped. Gender-affirming hormones can also be an option as a teen ages, such as the testosterone that Dylan Brandt is currently injecting. These treatments, they noted, have been around for decades; they are proven safe.

But importantly, Strangio and Tang said, this bill has serious implications for criminalizing evidence-based healthcare and impacting the medical community’s ability to do its job. And it’s only one bill in one state; at least 20 states have similar bans in the pipeline. “You have to think of it as a human rights issue,” Tang said. “It’s a slippery slope. It’s setting the precedent that you could be doing exactly what you and your professional society know based on data—but it doesn’t matter.” Strangio spoke from his perspective as a trans man: “People will go [to great lengths] for this care. I’m a little scared to even think about what people will have to do. We are not making people cis. It’s impossible. So what you’re causing people to do is take more risks to be who they are. Increased risk, increased negative health outcomes. That is deadly.”

The governor’s decision, though a moment for celebration for the trans community, was short-lived. The Arkansas legislature voted 71-24 and 25-8 to override the veto the next day. And HB 1570 is not the last anti-trans bill that Arkansas will consider this session. “The legislators are so focused on targeting trans youth in this way, it just feels like this very specific, super vulnerable population that this entire block has decided it’s going to be the flashpoint of politics for the next year,” Eckelhoff says. To local activists, it’s the depressing reality of their limited power in the face of larger interests—like the right-wing national Family Research Council—that overshadowed their opposition to the bill during hearings in the state house.

Rumba Yambú, the co-founder of Arkansas’s Intransitive, a trans resource center, sounds defeated when we speak just after the bill has passed. Yambú recalls testifying with fellow activists in the state house and enduring a campaign of intimidation. “We would have eight, nine, sometimes ten cops inside the hearing, in the hallways, watching us [walk] to the bathroom—constant surveillance.” When their experts attempted to provide testimony, or a parent of a trans youth prepared to speak, Yambú says, they would be cut off within minutes. Breshears, who also testified, was depressed by the legislators’ response—or lack thereof. “We’re pouring a lot of ourselves into those testimonies, and we’re rarely respected for it,” she says. “We sat in front of legislators and told them how kids were going to kill themselves over these bills, and they just had no emotion on their face.” Yambú would like to have seen the major corporations that show up for Pride parades support these trans causes—instead of donating to the legislators who are passing these bills. “It’s hard to fight against so much money,” Yambú says.

A raft of anti-trans bills, challenged

With a record number of anti-trans bills on state house dockets around the country this year, many of the fights have only become more complicated. In South Carolina, an anti-trans sports bill was nixed in mid-March—a rare win. In Idaho, an anti-trans sports bill passed in 2020 remains unimplemented after a legal challenge was upheld. In South Dakota, the governor ended up issuing two executive orders that effectively ban trans girls from participating in girls’ sports, after the bill became tied up in a legislative back-and-forth. In North Carolina, a bill prohibiting surgeries up to age 21 seems unlikely to succeed, thanks to a Democratic governor.

Next up in Arkansas is HB 1882, which would effectively force public institutions to ban trans people from using bathrooms matching their gender identity. For trans residents, fighting this onslaught of legislation is exhausting. “It’s not trans people’s responsibility to make cis people stop abusing us,” says Eckelhoff. “We were always taught, you know, love the sinner, hate the sin. How about just stop at love?” To Eckelhoff, Breshears and Brandt, who have made their identities public to be able to better support their communities, it’s time for everyone else to step up—and let them live freely. “You don’t have to understand me or agree with me to respect me, and to honor my civil rights that everyone should have,” says Eckelhoff.

Breshears, though, has a simpler message to the trans youth, like Dylan Brandt, currently caught in limbo: “I love you, and I see you and we’re going to keep fighting for you. This is not over. And we’re not done doing the work.” For now, the Brandts are just focused on getting through the rest of the school year, one day at a time. “I will do whatever I need to do to make sure that he gets what he needs,” Joanna says. “We’ll just have to have to wait and see, and I’m going to try and have a backup plan. But I’m gonna still hope that everything works out.” Dylan is looking forward to returning to school in-person next fall. With luck, they will still be in Arkansas.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Raisa Bruner at raisa.bruner@time.com