For years, whenever our children asked us if we could get a dog, my husband and I had some vague and only slightly encouraging go-to responses, such as, “Someday?” and “Maybe when you’re old enough to help.” Then came 2020, the year of our pandemic dread. Sometime between my mother’s live-streamed funeral in the spring and back-to-school that never quite happened in the fall, “maybe” gave way to “yes” and “someday” became “as soon as possible.”

Saying yes to the dog was very much about saying yes to our kids in the worst year of their lives. They’d lost so much with and during the pandemic—their grandma, their great-grandma, their school routines, the ability to spend time with friends and family. Like parents everywhere, my husband and I have spent the past year fretting about our children. We’ve been doing a lot of wellness checks, probably annoying them with attempts at probing heart-to-hearts, watching them for signs of anxiety and depression. It hasn’t been difficult to drill down on the source of our sadness—we’ve all been depressed since my mom died—but knowing the reason, knowing that we have a right to be sad, doesn’t make it any easier to be sad all the time.

For all of us, my husband and me as well as our two daughters, getting a puppy became an obsession. “This dog is going to be the family comfort animal,” I explained to friends. PUPPY DAY!!! was soon recorded and circled on the calendar. The kids picked a name and refused to consider others. My older daughter created a small yellow sign that read PEGGY for a very large crate. Whenever I was feeling particularly low, which was often, I would go online and start looking for supplies and puppy toys. Soon the four of us couldn’t even work up much angst over the coming pandemic winter, so focused were we on meeting our new family member and becoming, finally, the Dog People we were meant to be.

No doubt you’ve heard of the pandemic-pup phenomenon. By the time our new golden retriever came along, in mid-November, to plunge our household into joyful chaos, several families we know had also gotten dogs. One went “just to look” at a litter of puppies and wound up bringing home a goldendoodle on the same day we got Peggy—without so much as a crate or food bowl ready. Holdouts teased us for giving their children additional ammo for their own pet campaigns: “Way to make it that much harder for the rest of us,” a friend told me; “I want my kid to meet your puppy, but also my kid should never meet your puppy,” a neighbor said. While I’ve heard that some people regret their decision to get a pandemic pup, this is frankly impossible for me to relate to. In fact, our family is already discussing the day, perhaps in two or three years, when we might bring home another dog.

It’s not that it’s been easy. Peggy, now 6 months old, did house-train reasonably quickly, and she is sleeping through the night, but our living-room rug and nearly every piece of furniture we own should probably be replaced. Peggy is, in many ways, your typical pandemic puppy: she’s terrible at being alone; she has yet to accept long daytime stretches in the crate; she will pace and sometimes whine when she doesn’t know where any two of us are at a given time. (We are just in other rooms in the house, Peggy! We literally never go anywhere!)

But it’s fine, because it turns out we humans are also codependent and constantly crave the dog’s company. Why would I make our perfect pup cool her heels in a crate when I could have her sleeping on my feet while I work? Why would my kids want her “self-soothing” in a room by herself when she could be sitting at their knees, ready to be stealthily petted whenever they get frustrated or bored with school Zooms? A friend floated the idea of doggy day care, and even though I know Peggy would probably love the socialization, I admit my first selfish reaction was: “But I didn’t get this dog so that other people could be with her all day!”

Are we setting ourselves up for disaster? Perhaps. Will Peggy know how to deal with a mostly empty house when my kids return to school, my husband returns to the office and it’s just the two of us all day? Unlikely. Can any of us work up the energy to care or change course? Absolutely not.

I’m often surprised to find myself with this dog at all, despite how obsessed I’ve become. I like dogs well enough, but I’m also highly allergic and never really knew whether I could be a true Dog Person. I suppose my attitude for much of my adult life was “dogs, how nice for you/other people” (hardly an opinion I could express to my dog-loving family or on the dog-obsessed Internet). For years, I assumed that if we ever got a dog, it would be mainly for my husband and kids, and I would have to let them do most of the snuggling or else suffer constantly red, itchy eyes.

But by the time we got Peggy, I couldn’t pretend she was just for the kids. I’d been looking forward to bringing her home for weeks, and was probably more desperate than any of us for something good to happen. It was my lap that Peggy curled up on to sleep all the way home. I’m the one who lets her lick my face and eat my toast and break the house rules. I take three different allergy medications just to share a home with her.

It now seems so obvious that I would be this way. I’ve never been more in need of comfort and a limitless source of uncomplicated love.

In the foreword to her little dog-centric collection A Dog Runs Through It, poet Linda Pastan refers to one of her many dogs as “the dog of my life,” as in the love of one’s life. That is how I feel about Peggy. I tell her several times a day what a perfect angel she is, using a tone I wouldn’t have dreamed of using even for my children. I direct my family members to look at her, as if they don’t look at her all the time anyway, and note how especially beautiful she is. I’ve filled my Twitter and Instagram feeds with pictures of her; multiple friends text me asking for Peggy photos when they need a pick-me-up. Every night, before bed, I spend a couple of quiet, peaceful hours enjoying cuddle time with her on the couch she wasn’t supposed to be allowed on.

It now seems so obvious that I would be this way. I’ve never been more in need of comfort and a limitless source of uncomplicated love. Sometimes I almost worry that we’re going to overwhelm her, given how much we all love and need her—that it’s too much pressure to put on one puppy. And sometimes, because I’ve lost two parents in two years, I’m afraid to love another being that’s mortal. But even when we’re in the deepest pain, we need to love and be loved. Having a new puppy doesn’t erase our grief, of course—and that wasn’t the goal—but part of the grieving process is also slowly finding space for other pursuits, reminding yourself why you are still alive, taking what joy you can.

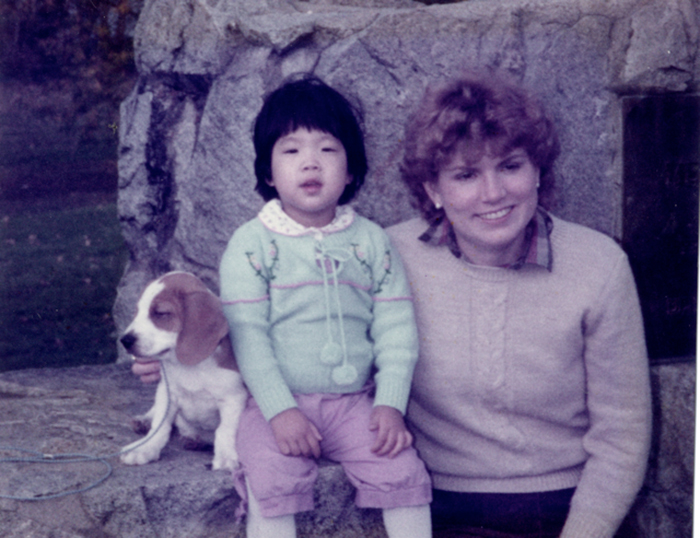

My mom loved dogs, as did my grandmother; they died within a month of each other last year. When my mother was dying, one of her biggest fears was that Buster, the beloved new dog of her widowhood, would have nowhere to go. Despite her allergies and mine, she always seemed to have a dog in the house, except when my father was most ill toward the end of his life and she was concerned that a dog underfoot would cause him to trip and fall. In so many of my favorite photos of her—the ones I keep on desks and shelves, so I never have to look far to see her face—she’s grinning, with her arms wrapped around one of her cherished dogs. I can’t always name the year or the place or the animal, but I can see my mother happy, and remember how her worry and anxiety and even her deep fear of death would be eased when she had a dog to dote on.

I do not believe in fate, nor do I really think anyone guided our dog to us, in the way my adoptive parents long believed that God intervened to guide me to them. But in my more fanciful moments, I’ve almost wanted to believe in the comforting fiction that my mother, or someone, knew we needed this dog at this time. In getting a dog of my own, one I’m sure she would have loved, I also feel I’m finally doing something my mom would have been able to relate to—unlike, say, my writing, or the fact that I’ve settled (in every sense of the word) on the East Coast. I suspect she would have called Peggy her “grand-puppy” and sent her plenty of toys and treats, the way she always seemed to find time and money to send gifts to my kids throughout the year, not just on their birthdays. She’d have peppered me with questions about the dog, her likes and dislikes, her habits bad and good, her appetite and sleep and training “progress.” When she came to visit, she would have been glad to offer Peggy a new warm lap.

When I tell people that Peggy has saved me this year—saved our whole family—it’s true. We still miss all the friends and loved ones we can’t see, our old routines, the feeling of relative safety. We will always miss my mom, my dad and my grandma. But Peggy has given our weary, grieving family a new shared focus, an emotional center that isn’t all about our loss. She’s given us all a new place to put our love and brought us back to ourselves.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com