In the first episode of the new Netflix reality series Marriage or Mortgage, engaged couple Liz and Evan are torn about their future. The last of their friends to get married, they are moving from Naples, Fla. to Nashville, Tenn., for Evan’s job. They’ve got $35,000 to spend, and as the show’s title suggests, they’re choosing between either a wedding or a house. They know that if they buy a house, it’ll be years before they can afford the wedding they’ve been dreaming about. While spending the money on the house feels like the practical choice, having a wedding is important to them, too. “I feel like I was misled in all my rom-com experience,” Liz says.

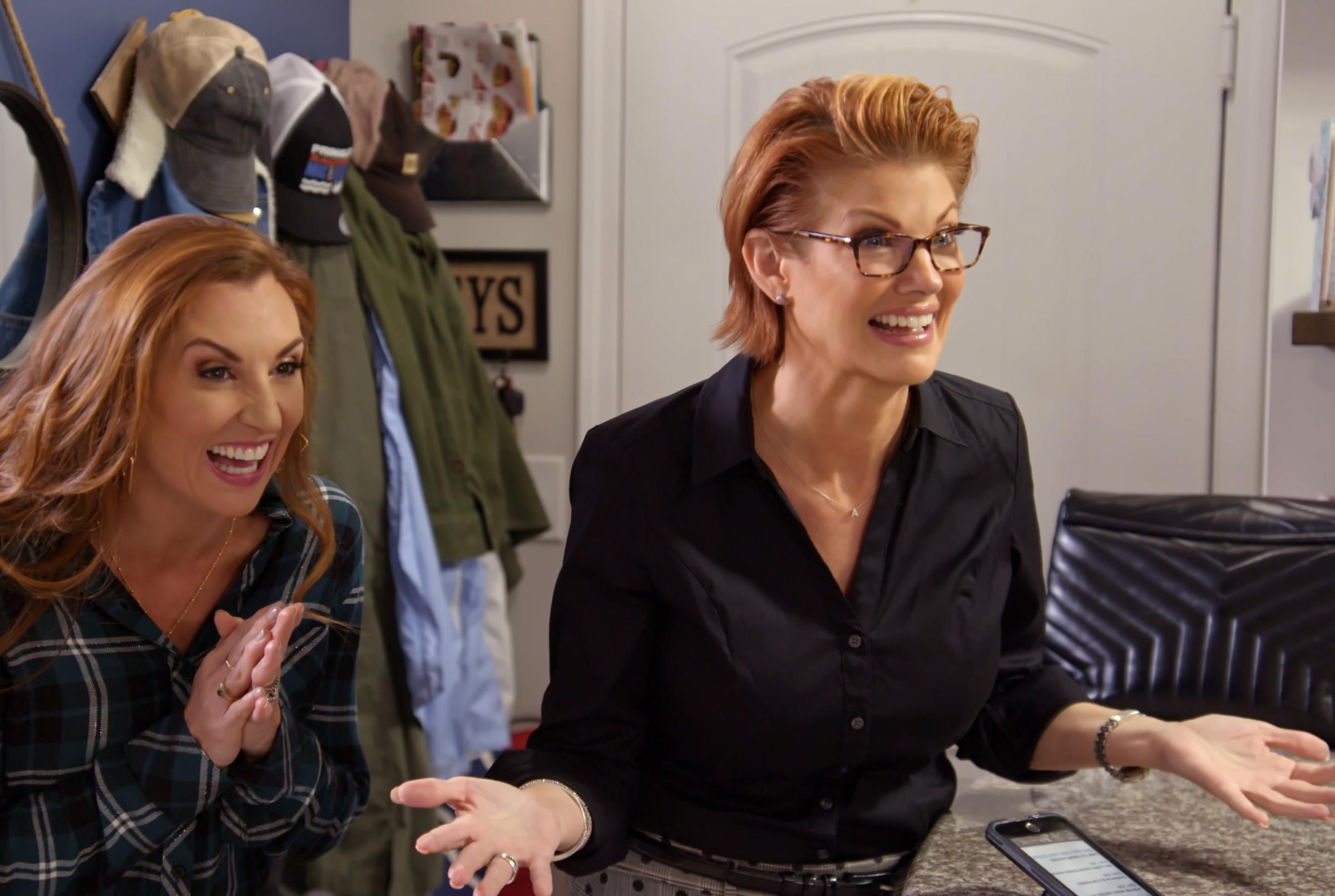

The 10-episode series, which drops on March 10, follows different couples in Nashville facing the same dilemma. Each episode focuses on one couple as realtor Nichole Holmes shows them homes that fit their budgets while wedding planner Sarah Miller takes them all over the city to tour venues, try on wedding dresses and taste food for hypothetical receptions. It’s a lighthearted show—a Selling Sunset and Say Yes to the Dress crossover that will surely find a fanbase among those looking for a breezy reality TV fix. But behind its cheerful facade, Marriage or Mortgage leaves much unsaid about the larger economic forces that make this decision particularly challenging—for those to whom such a decision is available in the first place. It’s certainly not the mission of a show of this nature to dig deep into the economics of it all, but it may leave viewers wondering about what’s led Americans to a point where milestones we’ve been conditioned to see as part of the American Dream feel increasingly out of reach.

Throughout the series, Holmes attempts to persuade the couples that buying a home is the best investment they can make, and Miller tries to convince them that a wedding day is a different kind of investment—an emotional foundation for the rest of their lives. While we’re not privy to the process by which these couples were cast for the show, one clear criterion was that they all fit in a particular financial category where they are not in a position to afford both a wedding and a down payment on a home, but they have enough savings to be debating detached garages versus signature moonshine cocktails. This is a position that may be familiar to many viewers (and certainly to millennials, like most of the couples in the show) though it is still a privileged one, as so many across the country struggle just to pay rent, especially since the pandemic began.

Already, people are calling the premise of the show depressing. The inability of Americans to afford both a (certain kind of) wedding and a home is not a new phenomenon—but it speaks to both broad economic trends in the country and how they play out when it comes to individual financial decisions. TIME turned to personal finance and housing finance policy experts to understand the historical underpinnings of the show’s central decision and what it says about the myth of the American dream.

The costs of weddings is on the rise

As captured in the show, weddings can cost a lot of money, and the industry has only gotten more expensive over time, especially over the last decade. In 2007, the average cost of a wedding was around $16,000, according to WeddingWire. Ten years later, that number increased to $28,000. By 2019, the average cost of a wedding had risen to $33,900. (This number dropped to $19,000 in 2020 due to restrictions on large gatherings during COVID-19 but is expected to rise again.)

This higher price tag comes from a few places, including bigger guest lists and couples opting to personalize their weddings, paying for services like live entertainment and signature cocktails. Even without all the bells and whistles, wedding receptions can be expensive: in 2018, the average price of a wedding dress was $1,700, catering was $6,700 and the venue was $9,000, according to WeddingWire’s 2019 Newlywed report. “As someone who has gone through the process myself, and professionally works in the personal finance realm, it was mind-boggling to me just how insanely expensive weddings were,” Erin Lowry, author of Broke Millennial Talks Money, tells TIME. (Lowry is a contributing writer to NextAdvisor, a personal finance site published in partnership with TIME and Red Ventures.)

Social media plays an outsize role in planning these days, and adds pressure to create events that look as fun as they feel. After getting engaged, 62% of couples said they increased their social media usage, according to The Knot Social Media Survey 2016, and 7 out of 10 were using social media “for wedding planning more than anything else.” Not only are they finding inspiration, as well as hiring wedding planners, off of social media, couples are also actively thinking about how they can make their wedding as “Instagrammable” as possible. This includes paying for custom Snapchat geofilters and tagging photographs with wedding hashtags. Seventy percent of brides shared their big day on social media within the first 24 hours of getting married, according to the Knot.

Lowry says that the big issue with wedding planning is that it is an emotional decision. “None of this is rational thinking. It’s completely an emotional decision where you have so many people weighing in,” she says. “When it comes to home ownership, oftentimes it’s one, maybe two people weighing in on it, but when it comes to weddings you’ve got parents, siblings, friends—everybody has an opinion.”

The barriers to home ownership

A big factor in what makes home ownership less accessible for many Americans is what it takes to qualify for a mortgage. Lenders look at how much debt you carry, the income you bring in, and your credit score, among other factors, and they typically want to see at least two years of consistent income, which can be difficult to capture in our growing gig economy. This means that inconsistent income, whether it’s a person’s primary or secondary source of income, often isn’t counted. Laurie Goodman, co-director of the Housing Finance Policy Center at the Urban Institute, gives an example: “If you think of an Uber driver who has a full-time job and then sometimes drives five hours a week and sometimes drives 20 hours a week, they’ll be lucky to get that five hours a week counted.”

Americans also carry a lot of debt, with the average American carrying around $90,000, which can drive home ownership further out of reach. This includes consumer debt, like credit card debt, which can impact your credit score and is not necessarily indicative of a person’s entire financial situation, such as staying on top of rent or utilities. It also includes student debt, which can hinder a prospective homeowner’s ability to qualify for a mortgage. Millions of Americans, especially millennials, are carrying enormous amounts of it. Lowry says that when she got married, her husband had about $50,000 worth of student loans. They currently do not own a home and instead rent in New York City. “That’s what we focused on attacking first,” she says. “Most people I know personally have loans or married someone with loans, and that’s a huge monthly cost if you go the aggressive repayment route, trying to pay those off at a rapid clip, that’s your down payment right there.”

This is a big barrier to entry when it comes to accumulating savings, particularly for younger Americans. “Everyone thinks that millennials are just out here drinking up their own paycheck or traveling away their paycheck, and I don’t find that to be so,” says Tiffany “The Budgetnista” Aliche, author of Get Good With Money. “I find that a lot of people have regular jobs with regular bills and they’re like, there’s nothing at the end of the month. How am I supposed to save?”

Affording the down payment is what renters name as the number one barrier to home ownership, according to a 2018 report from the Urban Institute, which relied on data from the 2018 Zillow Housing Aspirations Survey. “Down payment is certainly a huge challenge and is usually the number one for most people—they find it very hard to save,” Goodman tells TIME. “There’s a lot of down payment assistance programs out there, and a lot of people are just unaware of it. If you ask people how much money they need for a down payment, they will give you an answer that is way higher than the actual number.” Access to home ownership is also remarkably stratified based on race. According to a report from the Urban Institute published last year, the Black-white home ownership gap in 2018 was at its highest level—30.5 percentage points—in 50 years.

A lack of education in personal finance

Aliche, a personal financial educator, finds that most people don’t know the first step in pursuing homeownership. “I remember when I was trying to buy my condo at 25, I literally Googled ‘how to buy a home’ because I didn’t know where to start,” she says. Lowry, also a personal finance expert, agrees that the average person does not know much about real estate and investing. “We don’t just magically self-actualize like, O.K., I’m 25, all of a sudden I have all the knowledge implanted about how to buy a home and build my retirement plan,’” she says. “Then the problem, too, is that because it feels like everyone else around us knows how it works, we don’t want to ask because we don’t want to look stupid.”

And our lack of financial literacy goes beyond questions about home ownership. The pandemic has forced many people to consider how they manage their money—almost 90% of respondents in a recent survey form Charles Schwab said that they believe their lack of financial literacy has led to social issues. And 65% want schools to provide financial education. This desire to understand personal finance existed long before the pandemic—Aliche says in her business she’s seen people, especially women, become more conscious about their finances. “Folks, including women, have started to realize that financial strength and having a strong financial foundation is critical,” she says.

Lowry believes that prospective homeowners should approach the process much like the way people strategize around paying for college. There are scholarships that exist that many students may not know about, in the same way that programs exist for people who want to own a home. And she thinks that flexibility is key. “What parts are you not willing to compromise and what parts are you like, I would love to have ‘X amenity’ but if you don’t have it, it’s not a deal breaker, and to truly just look at homes in your budget,” she says, adding that it’s a mentality helpful in planning a wedding, too. This conversation is modeled in Marriage or Mortgage. In each episode, the wedding planner and realtor have the couples explain their priorities for both a home and a wedding, clarifying what is the most important to them, and what they can live without.

Home ownership and the American dream

Home ownership has long been tied into the concept of the American Dream. And Goodman stresses that it is such a good way to build wealth because it’s a forced savings plan, a source of stable housing and it locks in your housing costs. She adds: “Home values go up over time and will continue to go up because there’s a supply-demand imbalance.” Aliche also notes that when done right, a mortgage can be an investment in a couple’s future. “In the United States, home ownership is one of the cornerstones for wealth if done correctly,” she says. “Meaning that you purchased a home in an area where it’s likely to appreciate in value or maybe you purchase a home and you’re able to pay off the mortgage in a timely manner, and then maybe rent it out one day or at least maintain it.” Because of that potential for equity and appreciation, homeowners tend to have a higher average net worth than non-homeowners. According to data from the Federal Reserve, the median net worth of a homeowner in 2019 was 40 times that of a renter.

But the path to homeownership, already inaccessible to many, may not be for everyone even if they can afford it. “There is this misconception that home ownership is the holy grail of adulthood and that you’re not financially sound until you own a home,” Lowry says. “It’s been beautifully packaged as part of the American dream, but in reality is not a necessity to be financially stable.” She does acknowledge that, when it comes to the decision the couples on Marriage or Mortgage are making, a home can be looked at as an asset in a person’s overall financial portfolio, as long as it is a house they can afford, while a wedding is a purely experiential move. The most important piece, she finds, is for couples to look at what is most beneficial for them financially as well as what’s beneficial for their mental health.

Aliche went through the exact dilemma that the couples in Marriage or Mortgage are grappling with. She and her husband opted to buy a house instead of having a big wedding, but she doesn’t judge those who make the opposite choice. “As a financial educator, I think there’s enough shame and judgment in the industry,” she says. “My job is to give you all the numbers and stats so you can make the best choice for you.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Annabel Gutterman at annabel.gutterman@time.com