My husband had been in the hospital, critically ill, for weeks one day when I broke down in tears during a workout. Concerned gym buddies consoled me and someone said, “You’ve got to stay positive!”

“Do I, though?” I wanted to ask. I was urged to stay positive a lot during the years I was a caregiver for my husband Brad, through two kinds of lymphoma and a stem cell transplant that nearly killed him. The advice was always well meant, and I always forced a smile, but inside resentment flared.

I left mad, even though I’d gone to the gym to keep up with my self-care, following that other advice often given to caregivers: you have to take care of yourself. I bristled at that, too; self-care added more items to my ever-growing to-do list. Other variations on the stay-positive theme touched a raw nerve: “You’ve got this!” led me to wonder if I had a handle on anything, and at “stay strong” I wanted to collapse into a weak heap, preferably while wearing my softest pajamas.

Staying upright rather than taking to my bed felt like a victory; it seemed inconceivable that I might become, much less stay, positive.

One day as Brad lay unconscious in his hospital bed, the oncologist told me his odds of survival were about 10%. At that point, staying upright rather than taking to my bed felt like a victory; it seemed inconceivable that I might become, much less stay, positive.

American culture exerts enormous pressure toward positivity, expressed most famously by Norman Vincent Peale’s 1950s bestseller The Power of Positive Thinking. Recent years have seen a backlash, from Barbara Ehrenreich’s incisive Bright-Sided to the growing recognition of “toxic positivity”—the insistence on an upbeat attitude, which can invalidate a person’s experience, leading to guilt, anger and increased stress.

So what does help when a friend or family member is in the thick of caregiving, or any crisis? First, offer space for the full range of their emotions, on their terms. There’s immense power in a simple text telling a friend you’re there for them, particularly if you add this magic phrase at the end: “No need to respond.”

When I was overwhelmed, keeping up with communications was tough, and I appreciated friends who explicitly took the pressure off. I knew they saw and could handle my real experience: often harried, sometimes far from positive.

When it comes to practical assistance, try to offer specific help that the caregiver doesn’t have to ask for. However kindly meant, “What can I do?” puts the onus back on your overwhelmed friend to come up with a suitable task, increasing their mental load.

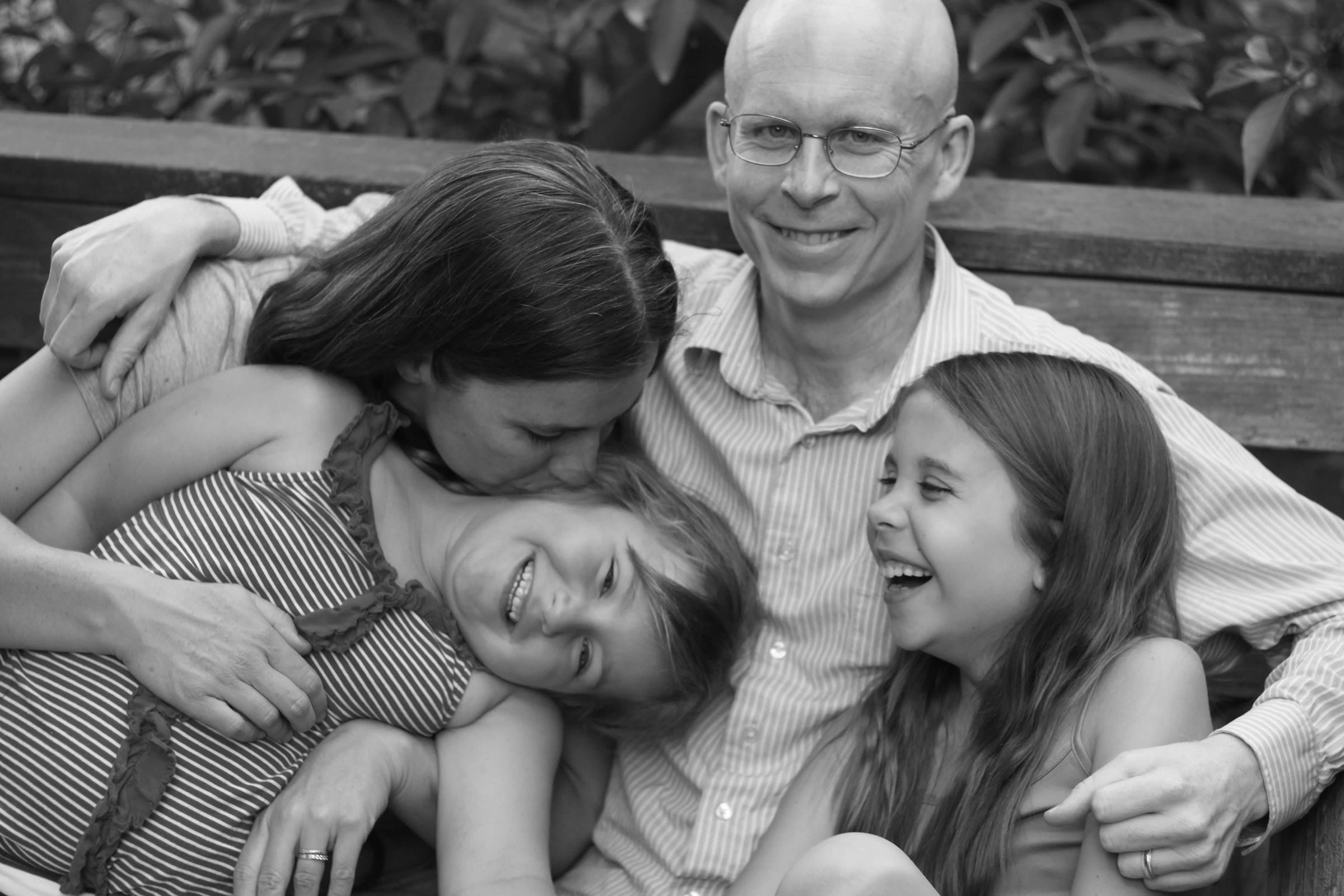

I still tear up thinking of the matter-of-fact generosity extended by the parents of our then-6-year-old’s best friend. They made a standing offer to take our daughter every Sunday, and for almost a year, we dropped her off weekly, no questions asked, for a fun day with their daughter—and a needed break from the caregiving sandwich for me.

Likewise, I’ll always be grateful to the friend who asked to set up the “meal train” that kept us fed for more than a year, and the many people who signed up for it. If you’re far from someone you want to support, gift certificates for meal delivery and errand or laundry services are perfect—or you can tailor your help even more, as one friend did after I told her that chemo-related taste changes made Brad unable to tolerate metal utensils. Her surprise shipment of 500 compostable, disposable forks was exactly what I never knew we needed.

An acquaintance knew we liked a particular bakery’s bread and would drop a loaf on our porch occasionally, texting me afterward.

Local friends texted when they were going to Target, asking if they could pick up necessities. One friend has revived such aid during the pandemic, offering grocery shopping to reduce our household exposure since Brad is still immunocompromised. Smaller gestures are sustaining too: an acquaintance knew we liked a particular bakery’s bread and would drop a loaf on our porch occasionally, texting me afterward.

These measures added up to something with greater impact than self-care: community care. Our individualist society is long overdue for broad systemic change in how we support care of all kinds, but informal community networks offer solace that peppy slogans can’t. On my hardest days, the actions of family, friends and even a few strangers gave me hope, relief, and—dare I say it—a genuine, not forced, feeling of positivity.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com