“Hello. This is a collect call from … [some voice that sounded like my brother’s ] a prisoner at the Michigan Department of Corrections. If you feel you are being victimized or extorted by this prisoner, call customer service at [some number rattled off too quickly for me to catch].” The digital woman gave more instructions: “To accept this call, press zero. To refuse it, press one. To prevent calls from this facility, press six.”

Why was Jeremiah calling collect? I’d added money to his account, or at least that’s what I thought. “Shit!” I hissed out loud, but not quite loud enough for my young son to notice. I fumbled through papers and moved books to find my wallet under a coffee mug.

In Michigan, people in prison make calls using pre-paid accounts. Calls cost $0.21 per minute plus a $2.95 processing fee. I spent $80.00 per month on my brother’s calls. Why was he calling collect? Did he forget his passcode? Had I paid JPAY again instead of ConnectNetwork, which also handled “inmate trust funds” for your loved one to buy soap and ramen noodles.

We still used JPay to send emails. They were the cheaper option. For $0.20 a page and $.20 an image, you could send a five-page letter. Add $1.00 for a holiday e-greeting card, an email could cost $3.00. Return stamps cost an additional $0.25. Jeremiah sent updates and asked about my family. At the end, he would make requests. He’d ask me to look up job-training programs or to send screenshots from his Facebook page. He’d ask for books and magazines subscriptions. He’d always need money for something. Gym shoes. A television set. An AM/FM radio. Each item cost twice as much from the commissary as it costs in the free world.

I sent Jeremiah $250.00 for his first Christmas inside, to buy boots and a television set. We didn’t know then that the MDOC takes half of everything over $50.00 in a 30-day period to cover legal debts. Jeremiah owed thousands of dollars: $600.00 for the checked-out public defender who met with him once for 20 minutes on the day of his plea deal, $1,611.00 for “court costs,” $400.00 for an extradition fee, and $68.00 for the “state minimum costs” to record his felony record. The cash that remained from his Christmas gift left enough to buy boots or a TV, but not both.

I was breathing hard now, my chest tightening. I couldn’t remember if you pressed # after your debit card number or wait to enter your security code. Shit, I thought. The digital lady was making me start over again.

What must it have been like for Jeremiah, standing at the phone on his unit? Was there silence? Did he hear me entering digits? After spending too long in my head, the call connected.

“What’s up, Ruby Scoober? What you doing?” Jeremiah asked. We caught up quickly. He told me a funny story about the men he lived with and asked about my wife and kids. “Let me ask you this,” he said, as he always did before making his requests.

I was always relieved to hear his voice, but I was always in the middle of something. That time I was writing. The previous time, I was in a faculty meeting. The time before that, I was on a date. No matter if I was sleeping or playing with my kids or trying to clear my mind, when the call came I had to answer.

Any boxer will tell you that the punch you don’t see coming is the one that puts you down: The collect call you didn’t expect. The court date you didn’t have the gas money to attend. The conversations with your children about why their uncle was in prison. The $2.95 processing fee that overdrew your account. The six $34 overdraft fees. The unexpected embarrassment as you sit at your desk, entering an order for 30 packages of ramen noodles. What it feels like when Michigan Packages runs out of the flavor of noodles he wanted. It’s these little things, the daily disruptions, that manage to put you down.

A million families live this way: Sending money they can’t afford. Making court dates they don’t have time for. Driving five hours only to be turned away, because the facility is on lockdown or because someone’s dress isn’t long enough. It’s the way the guard talks to you when you visit, and how you’re herded single file through dingy corridors to pay too much for microwave concessions. It’s watching your loved ones demolish that food and how they’re marched away when the visit ends. It’s feeling alone, though everyone you know has experienced this.

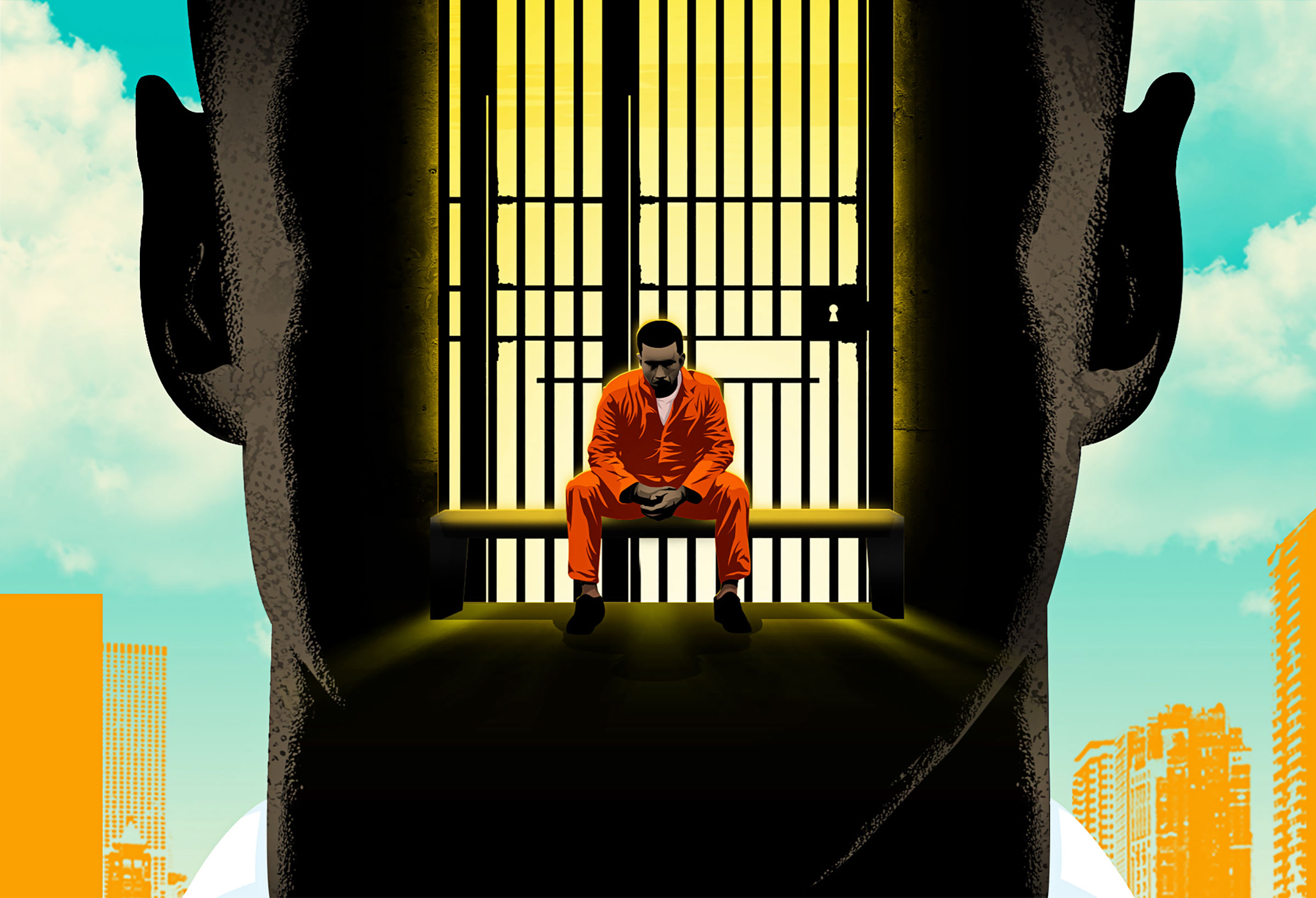

One in two Americans have lived some version of this story, because half of all U.S. residents and a full two thirds of all Black people have a loved one who has done time. However, it’s not just the family members who are frustrated. It’s especially hard for people in prison.

The combination of bad cell phone reception and a busy life means your incarcerated loved one can’t reach you. After four attempts, he wonders if your distance is intentional. It’s your tone when you finally accept the charge from frustrations they couldn’t have caused. He’s gone weeks without mail and months without a visit. He’s hearing another lecture from his younger sibling about what he should be doing with his life. He’s trying to raise his children through collect calls, 15 minutes at a time. He knows what he’s put you through, but he calls because he needs you.

Prison exacerbates these needs, and it escalates these tensions, changing the nature of even the most intimate relationships. But it’s not just like this on the inside. The prison is like a ghost, haunting formerly incarcerated people as they look for work, or a place to stay, or as they sit for dinners with the people they love most.

Upon release, people with criminal records are greeted by over 45,000 policies that dictate where they may go, with whom they may live, and how they may spend their time. These “collateral consequences” prevent them from fully participating in the labor and housing markets. Today, there are 19,219 employment restrictions that keep people with criminal records out of the workplace. 1,033 housing restrictions keep them from being able to rent an apartment. 3,954 restrictions limit their civic participation and 1,612 constrain their family and domestic rights. This means they may not hold most public offices. They may not sit on juries. There are hundreds of categories of employment for which they need not apply. They may not rent an apartment and will struggle to find a place to stay. In some states, they may not vote. But if all politics are local, the policies of mass incarceration are hyper local. Just pick a state. New York has 1,052 laws and policies that lock people with criminal records out of the economy. Michigan has 659. Illinois has 1,289, including 512 that target employment, 177 political and civic regulations, 30 housing restrictions, and 50 policies that regulate family life.

There are so few places where formerly incarcerated people can turn in their times of need. This is due to changes in liability law, which began in in the 1980s. Tenants sued negligent landlords when they were robbed or mugged in their buildings. The courts sided with the tenants, finding that crime prevention was part of every landlord’s responsibility. Landlords were fined under nuisance ordinances for letting their buildings fall into disrepair, for harboring drug users and gang activity, and for leasing apartments to people with criminal records.

In 1996, Congress passed the Housing Opportunity Extension Act, requiring public housing agencies across the country to evict tenants for “any criminal activity,” including crimes committed “on or off such premises” by “any member of the tenants’ household . . . any guest, or other person under the tenants’ control.” Almost overnight, private citizens were conscripted into the nation’s crimefighting machinery. Offering help to someone with a criminal record could now cost you your livelihood. Mothers were being evicted for the crime of letting their children, who had been to prison, sleep on their couch. Cousins, lovers, and friends who let people with records visit their home were evicted, too.

I knew that this is the world that my brother would reenter, where the laws that prevent him from getting a job or renting an apartment also made it risky for people to offer him help. And I knew that the support he needed in prison would pale in comparison to what he would need when he returned. My brother, like the 19.6 million people estimated to have a felony record, would enter an economy of favors, where he would be tasked with soliciting support from people who are encouraged not to help him to meet his basic human needs.

“You have one minute remaining,” the voice said. I jotted down Jeremiah’s requests. “I love you, bro,” my brother said. “I appreciate all you do.” “I love you, too, man,” I replied before the digital women disconnected the line.

Excerpted from Halfway Home by Reuben Miller. Copyright © 2021. Available from Little, Brown & Company, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com