“What are you afraid of?” Jaime Herrera Beutler, a Republican congresswoman from Washington state, demanded of her colleagues as they considered the second impeachment of Donald Trump. “I’m not afraid of losing my job,” Herrera Beutler said. “But I am afraid that my country will fail.”

There is more than fear swirling around the GOP these days. For years, Republicans stood by their President, muttering their doubts in private. They pretzeled themselves to defend his shifting whims, reframed his outrages as silly showmanship and rejected his first impeachment as partisan overreach. Absolute loyalty was what their voters demanded; any sign of deviation was swiftly punished.

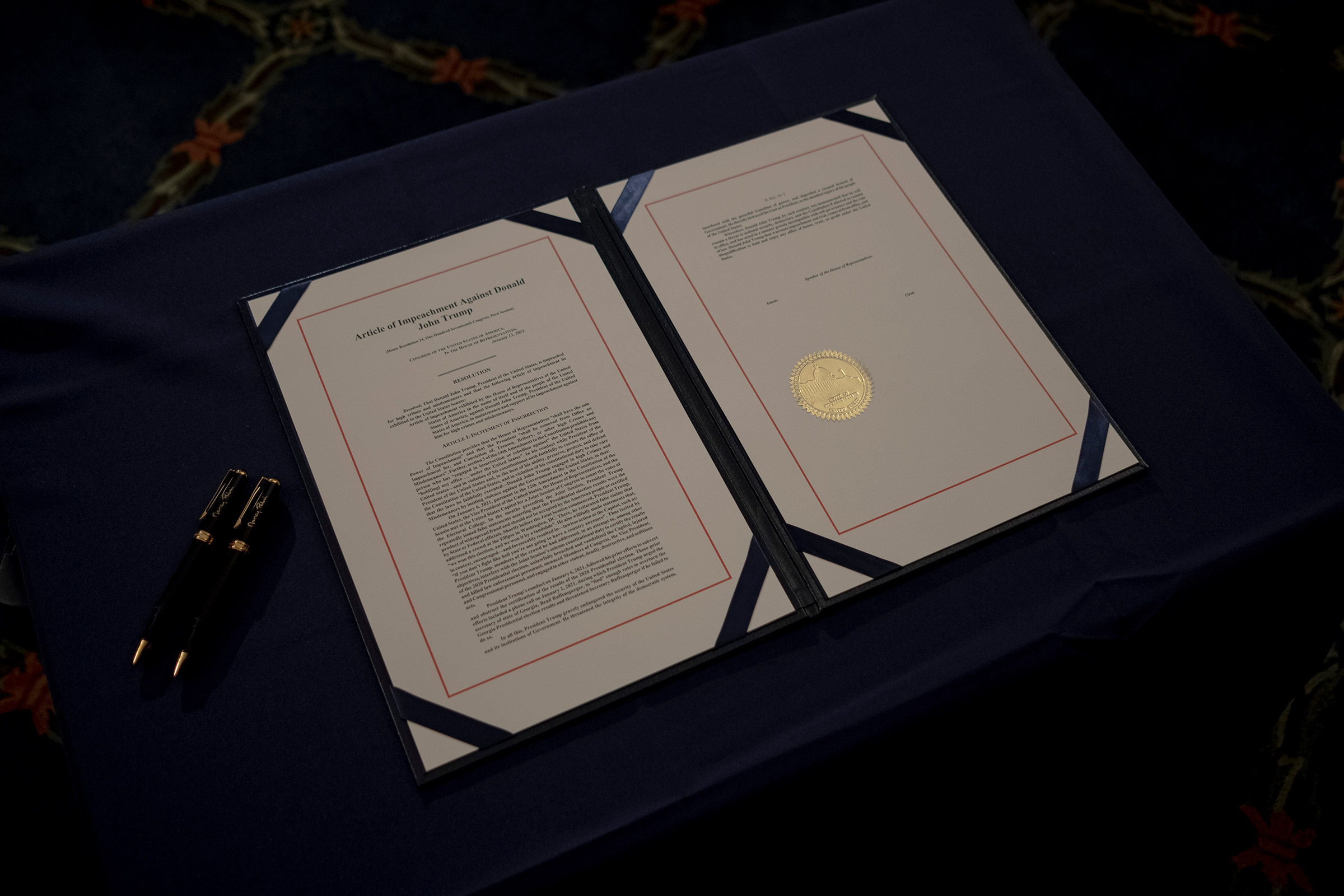

But in the dramatic final weeks of his term, Trump finally pushed his party to its breaking point—first demanding it reject truth and the democratic process by overturning the election he lost, then siccing his mob on the seat of government, with deadly results. Finally, on Jan. 13, 10 of the 211 House Republicans broke ranks and voted to impeach him for inciting an insurrection.

Trump may be done with Washington, but Washington—and particularly his adopted party—is not done with him. How the Senate will dispense with the first-ever post-presidential impeachment is an open question. Numerous Republican Senators have expressed openness to convicting Trump and potentially barring him from future office. That number includes the party leader, Mitch McConnell, who said bluntly on the Senate floor on Jan. 19, “The mob was fed lies. They were provoked by the President and other powerful people. And they tried to use fear and violence to stop a specific proceeding,” the ratification of President Joe Biden’s election win.

The Senate will try Trump for the second time once the House sends the impeachment over. McConnell has so far given his fellow partisans little guidance, leaving them to wrestle with their consciences and their political calculations alone. But the impeachment vote is just one of many questions confronting the GOP as Trump leaves office—questions that will determine the future of American politics and the shape of the Biden presidency, from congressional policymaking to voters’ choices in future elections.

How will the minority party respond to the new Administration, whose visions of unity Republicans can dash by withholding cooperation? What should the GOP stand for if not the cult of personality Trump forged? How much influence will Trump and his family continue to have on the party going forward? And how can Republicans win elections if they are trapped between a fanatical base of delusional conspiracists and a broader electorate that despises Trump?

Some top Republicans are hoping Trump’s hold on the party will loosen now that he’s out of office. Others believe a clean and deliberate break must be made to regain lost credibility. “You can’t just do things and act like they never happened,” says Republican John Kasich, the former Ohio governor. “Of course they are going to pay a price for what they did.” If the GOP doesn’t find a way to dump Trump and start anew, Kasich says, “the party will fall in on itself.”

THE IMPEACHMENT DILEMMA

The first turning point for the post-Trump GOP is fast approaching. It would take 17 of the 50 Republican Senators voting with all 50 Democrats to convict Trump of the impeachment charge of inciting insurrection. The Senate could then vote to punish the ex-President by prohibiting him from holding federal office in the future. That’s an appealing prospect for Republicans who would like to see the party move past a man who has mused about running again in 2024.

During Trump’s first impeachment trial a year ago, McConnell vigorously defended Trump against the accusation that his pressuring of the Ukrainian President for political favors in exchange for military aid constituted an abuse of power, and that he obstructed Congress by refusing to cooperate with its inquiry. This time, the taciturn Senate leader has not tipped his hand as the trial nears. “McConnell is not prone to hyperbole or theatrics,” making his recent forceful statements notable, says Scott Jennings, a Kentucky-based GOP strategist and former McConnell adviser. “We have a strong sense of fairness in this country, and I don’t know how you can look at the behavior of the President and not conclude he deserves some kind of punishment; whether it’s impeachment and conviction, I don’t know.”

Twelve more Republican Senators have said they are open to hearing the evidence presented in the impeachment trial, while 23 have indicated they would not vote to convict Trump and 14 have made no statement, according to a whip count maintained by the Washington Post. Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski, a sometime Trump critic, has gone so far as to say that Trump’s conduct made her reconsider her membership in the GOP. “Such unlawful actions cannot go without consequence,” she said. The Senators opposing conviction have mostly said it is pointless or constitutionally questionable for a President no longer in office; few have defended Trump’s actions.

THE OPPOSITION PARTY

Even as they consider impeachment, Republicans, as the minority party in both houses of Congress, must decide what posture to take toward the new Administration. When Barack Obama took office in 2009, Republican congressional leaders made the cynical—and ultimately correct—calculation that their fastest path back to power was to thwart his agenda. Biden hopes this time will be different. McConnell has been negotiating with the newly minted Democratic majority leader, Chuck Schumer, over how the two will share power in the 50-50 Senate. The two met on Jan. 19, and McConnell pushed to preserve the 60-vote filibuster requirement for most policy legislation, but no agreement was reached.

Normally, the Senate gets to work confirming the Cabinet before a new President takes the oath of office, but Trump’s behavior made that impossible. A push to quickly approve Biden’s national-security team was derailed Jan. 19 by an objection from GOP Senator Josh Hawley, who expressed concern over prospective Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas’ views on immigration. Democrats are girding for a replay of the Obama years, when Republicans, led by McConnell, put up a wall of opposition even to traditionally bipartisan or conservative proposals, and used procedural tactics to block executive and judicial picks. Republicans charge that turnabout is fair play after many Senate Democrats rejected Trump’s appointees wholesale.

Biden is preparing an ambitious agenda to confront the coronavirus and economic crises, but the Democrats’ majorities in the House and Senate are razor-thin. Whether the GOP decides to play ball or obstruct will have huge consequences for the country’s direction. “There’s nothing that says they have to go along with the Democrats’ plans, but they have to develop legitimate alternatives,” says Kasich. “They’re most comfortable being against things. But if you’re a party and you don’t have ideas, I don’t know what you exist for.”

THE IDENTITY CRISIS

There was a paradox to the party’s policy shifts during the Trump years. The outgoing President upended the GOP’s traditional stances on fiscal, social and national-security issues. He blew up the deficit, imposed tariffs that scrambled trade relationships, restricted immigration and embraced the world’s most despicable dictators. Yet he was generally disengaged with policy and lawmaking, never presented a health care plan and claimed a massive corporate tax cut as his only significant legislative accomplishment. Trump policed GOP lawmakers’ fealty to him with vigilance, yet rarely punished ideological deviations. Critics charged that the real substance of “Trumpism” was the racial and cultural grievances Trump delighted in inflaming.

In 2020, for the first time in the GOP’s 166-year history, the Republican National Committee (RNC) did not draft an electoral platform at all. Instead, it simply issued a statement of support for the President. The upshot is that what the party should stand for is more or less a blank slate, with some party veterans aiming to resurrect the orthodoxies of the past while others strive to reformulate policies in light of Trump’s rise.

“Republicans are going to have to figure out how to channel the ideas and themes that got Trump elected while moving away from the most damaging aspects,” says Joe Grogan, former director of the White House Domestic Policy Council under Trump. As examples of those ideas, he cited support for manufacturing and working-class jobs, deregulation, limited government and “American exceptionalism.” The question, however, will be whether any of those ideas exerts a pull on voters comparable to the force of Trump’s personality. “A cult of personality is always dangerous in a republic, because it leads to events like what we just witnessed” on Jan. 6, Grogan says. “That’s a result of people thinking an individual is more important than the Constitution.”

THE LEADER IN EXILE

No one yet knows how ex-President Trump plans to stay involved in politics, but few expect him to sit on the sidelines.

“I don’t think he’s going to ride off into the sunset. I think he’s going to enjoy being a former President much more than he enjoyed being President, quite frankly,” a former GOP official says. But the Capitol siege throws Trump’s future appeal into question, the official notes. “Three weeks ago, I would have told you he loves to be kingmaker, loves to hold an endorsement over someone’s head and can be a factor as long as he wants to be. But now it’s just so up in the air.”

If he is not barred from office, he is expected to keep a 2024 candidacy on the table in an attempt to freeze the field and maintain his influence in the party, even if he doesn’t go through with another presidential run. Trump retains control of a millions-strong email fundraising list that delivered more than $200 million even after he lost the 2020 election—with most of the funds going to his own political coffers, not the party’s. And while not all his handpicked candidates won their races, his endorsement has been a powerful force in GOP primaries. Already, Trump allies are seeking to purge those perceived as disloyal, from House GOP Conference chair Liz Cheney, who supported impeachment, to the governors of Arizona and Georgia, who rebuffed Trump’s election attacks. “I want you to know,” Trump said in a farewell video released Jan. 19, “that the movement we started is only just beginning.”

Trump’s political clout could be curbed by his bans from major social media platforms including Facebook and Twitter. Then there are the legal and financial challenges he faces: state and federal investigations into numerous scandals he’s implicated in, and hundreds of millions in debt about to come due for his businesses. But even if he’s done with elected office, it’s clear that politics has become a Trump family business. His daughter-in-law Lara Trump is considering a Senate run in North Carolina, her home state, and there is talk of a political future for his children Ivanka and Don Jr.

TIRED OF WINNING

Polls were eerily static throughout Trump’s term, unmoved even by such calamities as COVID-19. But for the first time, a significant chunk of Republicans moved away from Trump following the Capitol riot. Trump’s approval rating plummeted from the 40s to the 30s overall. Among those who consider themselves Republicans, 33% said the party should stop following Trump and take a new direction, and 12% said he should be criminally charged for his actions, in a recent Washington Post/ABC News poll.

If such defections hold, it would be a devastating development for a party already dependent at a national level on structural quirks that embed minority dominance, such as the Electoral College and the Senate’s overrepresentation of rural states. The siege also spurred a revolt among the traditionally conservative business class, as corporate political action committees announced they would no longer support lawmakers who objected to certifying Biden’s victory. The billionaire Home Depot retired co-founder and longtime Republican donor Ken Langone, for example, said on CNBC that he felt “betrayed” by Trump and would support Biden going forward. With Trump as their standard bearer, Republicans lost the House, the Senate and the presidential popular vote—twice.

Dissatisfied with the party’s insufficient loyalty, Trump has reportedly discussed forming a third party in recent weeks. But whether his faction is inside or outside the GOP, the party will be grappling with his influence for a long time to come. “That percentage of Republicans who continue to believe that the election was stolen will continue to be very vocal about it, and it’s just going to be a huge problem for us,” says Jeff Larson, a former RNC chief of staff who worked on behalf of the party’s Senate campaigns in 2020. “And you’ll have people that will try to appease them, and then it becomes worse. We need strong leaders.”

Pulling in the opposite direction are efforts by anti-Trump conservatives such as the Lincoln Project to reshape the party into a kinder, gentler, less authoritarian force. But as long as the rank and file remain loyal to Trump, the moderates will have a difficult job. “A mob of pro-Trump radicals and neofascists sacked the Capitol and forced Congress to flee. I hope that’s enough to make some sane Republican politicians ask, ‘How did we come to this?’” says Geoffrey Kabaservice, political director of the Niskanen Center think tank and author of an influential history of moderate Republicans. “Part of it is that Donald Trump is a sociopath, but there are also real problems tearing the country apart, and the Republican Party needs to try and address those problems if it wants people to turn away from Trump’s toxic legacy. It might not work. But it’s the only thing that might work, and it’s the right thing to do.”

With reporting by Leslie Dickstein and Mariah Espada

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Molly Ball at molly.ball@time.com