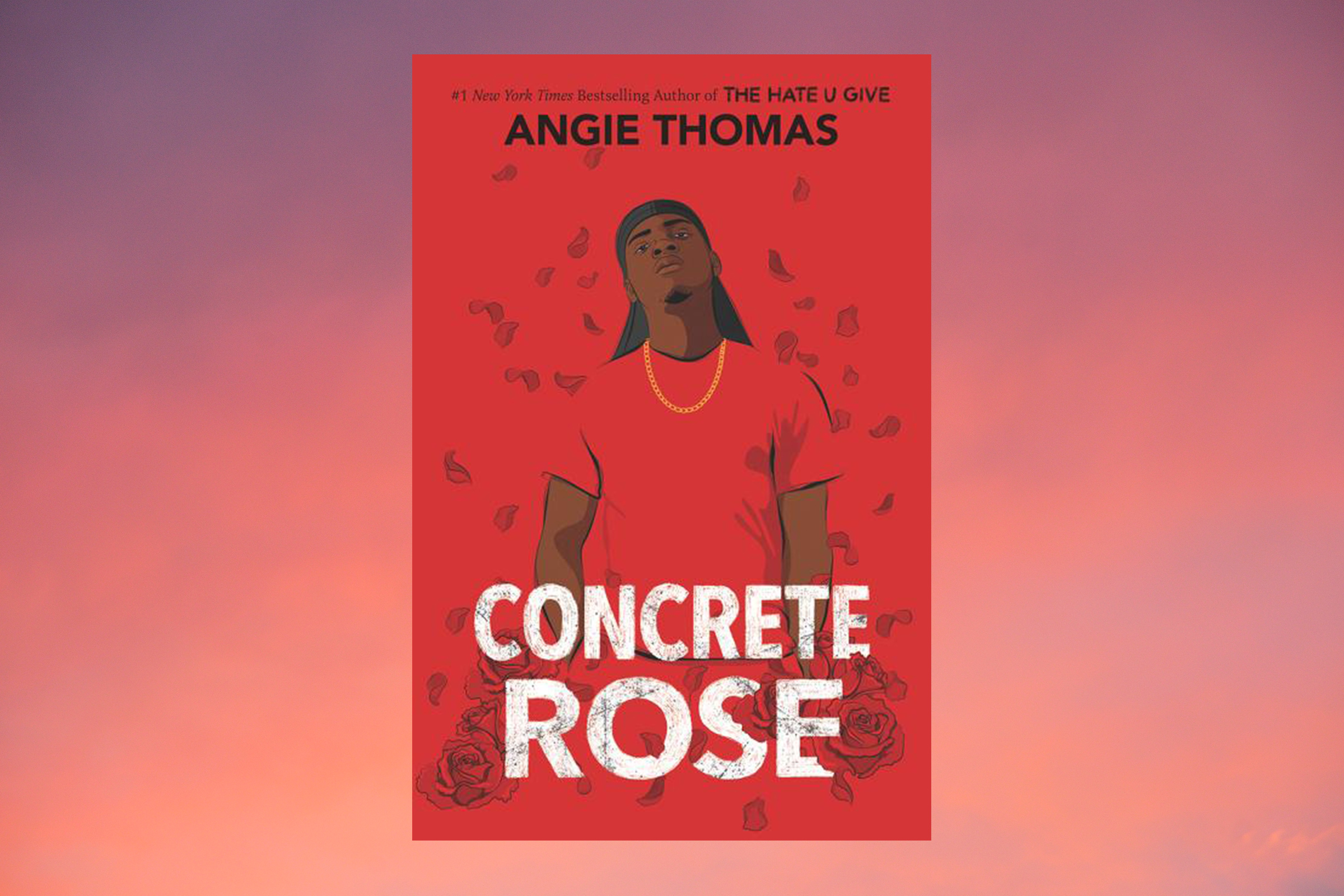

Is our cult of masculinity destroying us? Concrete Rose, Angie Thomas’ latest young adult novel, is a meditation on just that: the problem of boys pretending to be men. The book, out Jan. 12, is a prequel to Thomas’ smash bestseller The Hate U Give, which followed teenager Starr Carter after she witnessed her friend get shot and killed by police. Maverick was her father, and a standout character in the acclaimed 2018 movie adaptation, which turned Angie Thomas into a household name. Concrete Rose tells the story of Maverick as a 17-year-old high school senior and a member of the King Lords gang in Garden Heights, the fictional Black neighborhood where Thomas set both of her previous novels.

When we meet him in Concrete Rose, Maverick is the son of a mother who is working-class poor and a father who is serving a lengthy prison sentence. The teenager has inherited a gang affiliation from his father, and Maverick accepts the opportunity to make money on the side by selling hard drugs. He keeps his mom blind to his activities by doing odd jobs around the neighborhood, and because she works all the time.

From the get, Thomas imbues Maverick with innocence, humor and street smarts. He lives by the code of Garden Heights, where behavior is dictated by a fraternity of violence and aggression, but isn’t blind to the hypocrisy of gang life. Members are protected from rival gangs and the risks of their lifestyle, but the only way out is equally dangerous: to leave a gang, a member must risk his freedom or his life. When Maverick finds out he’s become a father, he’s forced to decide whether or not to take that risk.

Here, a familiar story of violence and poverty takes an important turn. On finding out about her son’s new situation, Maverick’s mother is tough but supportive. When he is faced with the financial pressures that come with giving up dealing, the neighborhood market owner, Mr. Wyatt, offers him a job, a different way to live. And when old friends try to pressure him into an unthinkable act, his father in prison—locked away but not absent—counsels the teenager on how a “real” man comes to a decision: not by succumbing into the demands of the street but instead by weighing the cost to those he loves most.

But what does it mean to be a man? For my brother Lindo, back in the ’90s, it meant throwing a fist to protect Mami against our stepfather, only to find himself flung to the streets. It meant renting a room in our Harlem neighborhood, wearing the flyest kicks around, and, thanks to his new occupation as a 17-year-old drug dealer, offering me the single best clothing item I owned as a teenager. My bomber jacket came off the shoulders of an addict who couldn’t buy what she needed with money. I was there that day—the woman asked me if I wanted it. Lindo was annoyed, but he smirked. He seemed to swell with newfound power. Now a man for real, he could gift his nerdy sister a jacket we’d never afford otherwise, embrace danger by way of a transactional hug and floss and sway all the way to prison, where he’d end up in a matter of months.

Concrete Rose, one of the most eagerly anticipated books of 2021, is being ushered into the world just as Donald Trump’s presidency ends—a presidency that has been defined, among other things, by the weaponization of toxic masculinity. Thomas’ genius is her ability to craft one man’s history in a way that illuminates the forces that brought us to this critical juncture. She thrusts Maverick into loss after loss after loss, the stakes higher each time. Manhood becomes the confining praxis toward resolution: Is he a man? How big of a man? How brave of a man? We come to understand that loss ushers Maverick to redefine himself beyond the confines of gender norms: he must see himself not as doomed to the legacy of his father’s actions, but as a parent and a human being focused on the future.

The cult of masculinity centers survival and the ability to thrive as a battle wrought between individual agency and the constraints of society. It has manifested over the past four years as a battleground of arrogance against science and entitlement over everything else. In Concrete Rose, Thomas demonstrates that a person’s ability to blossom is determined in part by his own choices, but that ultimately, just as it can lead a young man astray, it is the collective—the actions of his community—that can steer him through obstacles during times of need. In Thomas’ construct, community nourishes its most vulnerable member so he may redefine himself for good.

My brother faced many of these same life-altering circumstances. But unlike Maverick, he withered without the infrastructure of true community at each level—family, school, government. Halfway through his prison sentence, he was deported back to our birthplace of the Dominican Republic after an altercation, for violating the rules of his green card. The government did not even notify Mami that her son had been sent away. And in isolation, he has wilted beneath bedrock.

Thomas’ book holds a universal truth: Regardless of mistakes made, there is a way to break through concrete, to bloom wildly with freedom. It is possible to take all that is hard, cold, grey and transform it to a thing of unexpected beauty. But it requires all those around us to tend and cultivate.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com