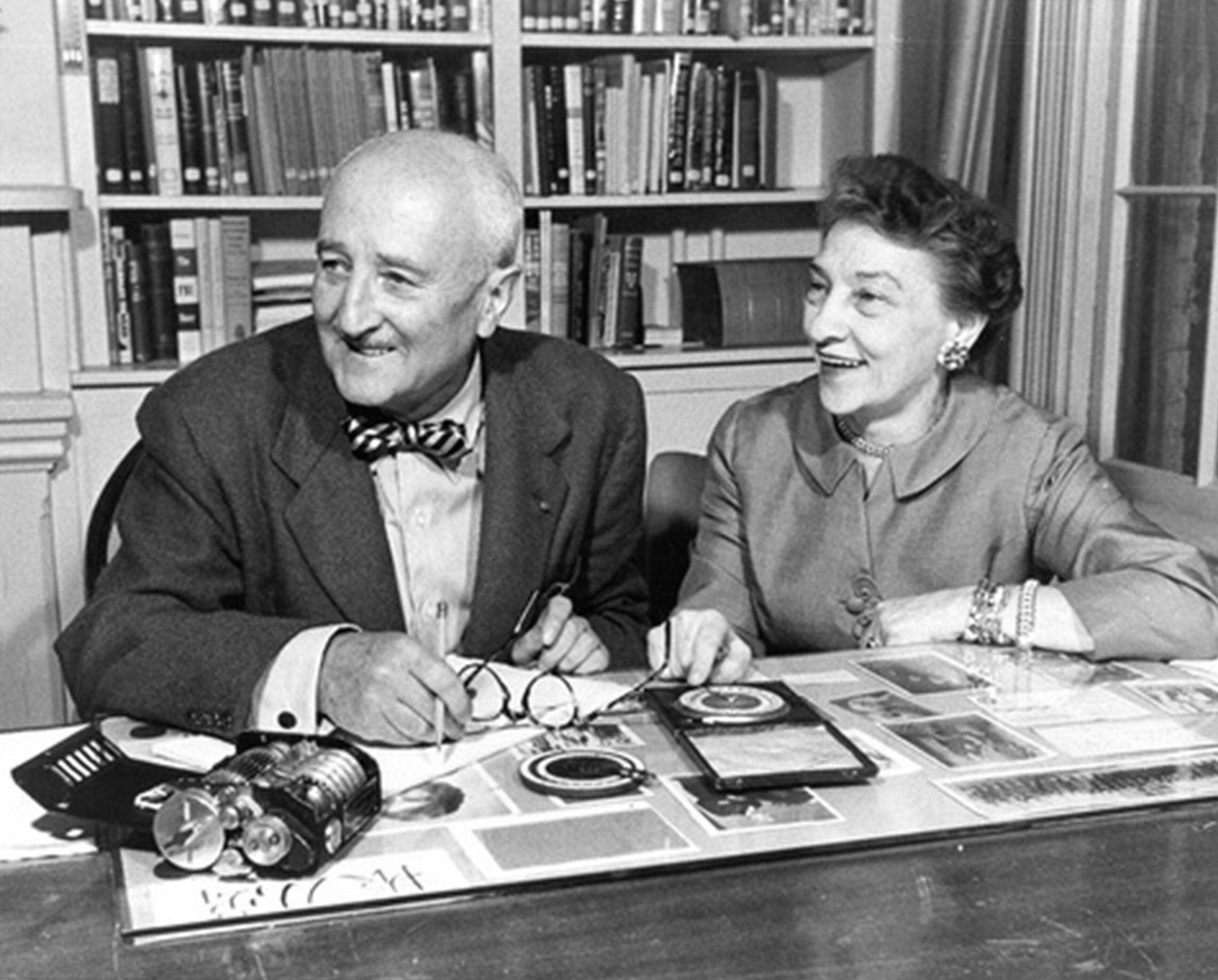

In October 1957, American cryptologist and codebreaker Elizebeth S. Friedman and her husband, William F. Friedman, were the subjects of a short article in TIME magazine about their new book debunking a long-held theory that William Shakespeare wasn’t the true author of his plays, and that a cipher was hidden within his texts pointing to the “real” author’s identity. “The Friedmans’ credentials are impressive,” commented TIME, adding that William led the team that broke the Japanese “PURPLE” code a few months before Pearl Harbor.

While William was considered during his lifetime to be America’s leading cryptologist, and is remembered today as the godfather of the National Security Agency, Elizebeth’s achievements have only received greater recognition in recent years, after World War II records detailing her role were declassified. In fact, the Shakespeare project, which Elizebeth had first encountered as a young woman in 1916, now seems like a minor side project compared to her other achievements. Widely known as “America’s first female cryptanalyst,” in World War I, Elizebeth and William directed an unofficial code-breaking team employed by the national government. During the Prohibition era, she was responsible for breaking codes used by narcotics and alcohol smugglers, incriminating high-profile mob-run rum rings, including that of Al Capone in New Orleans. But her biggest achievement was uncovering a Nazi spy ring operating across South America in 1943—a feat that J. Edgar Hoover took full credit for on behalf of the FBI. Friedman, meanwhile, took her involvement to the grave.

“She was a hero and she never got her due,” says journalist Jason Fagone, author of the 2017 book The Woman Who Smashed Codes: A True Story of Love, Spies, and the Unlikely Heroine who Outwitted America’s Enemies. “She was this amazing, hidden woman behind so many important secret battles of the 20th century.” Fagone’s book serves as the basis for a new PBS documentary, The Codebreaker, which uses archival letters and photographs to provide an inside look at Friedman’s life and work. It’s part of a renewed interest in Friedman’s legacy in recent years; in April 2019, a Senate Resolution was passed in her honor, and in July 2020, the U.S. Coast Guard announced that a new ship will be named after her. “She got written out of the history books,” says Fagone. “Now, that injustice is starting to be reversed.”

An intuitive gift for breaking codes

Born in 1892 in Indiana, the young Elizebeth Smith was a keen linguist from an early age, and graduated from college in 1915 as an English Literature major. She enjoyed reading and poetry, writing some of her own work. Her start in codebreaking was prompted by an encounter with the millionaire businessman George Fabyan, owner of Riverbank Laboratories, one of the first facilities in the U.S. founded for the study of cryptography. It was at Riverbank where Smith honed her skills in cryptography, and where she met William Friedman, whom she married in 1917.

While William had excellent intuition for breaking ciphers, Elizabeth had a different kind of intuitive gift for codes that no one else could see, says historian Amy Butler Greenfield. “She was extraordinarily good at recognizing patterns, and she would make what looked like guesses that turned out to be right,” says Butler Greenfield, who is featured in the documentary and is working on an upcoming biography of Friedman, titled The Woman All Spies Fear. The field of cryptography at this time was still young, and Elizebeth was one of very few women working within it. “Gender roles had not become a barrier because there was hardly anyone in code breaking at all,” says Fagone.

Just before Elizebeth and William wed, the U.S. entered World War I. The prominence of radio transmission meant that codebreaking was now a valuable skill, but the U.S. did not have a dedicated code-breaking unit at that time and was unprepared to gather intelligence by those means. Fabyan volunteered the services and expertise of the staff at Riverbank, establishing the first code-breaking unit in America, headed up by the Friedmans. The couple trained army personnel in deciphering messages, and also built their own sophisticated code systems. After the war ended, the Friedmans left Riverbank to work for the U.S. government, and in the 1920s, Elizebeth ran a cryptanalytic unit under the U.S. Coast Guard to monitor illicit smuggling rings—the first woman to ever lead such an initiative. She would intercept and solve the coded messages of mobsters and criminal gangs, delivering them to the Coast Guard. Elizebeth and her assistant’s work resulted in 650 criminal prosecutions, and she testified as an expert witness in 33 cases against narcotics smugglers.

Triumph and frustration in World War II

While Friedman ran her own code-breaking unit in the ‘20s and ‘30s, she felt frustrated by her position during World War II. She was assigned to monitor clandestine communications between German operatives in South America and their overseers in Berlin, yet she did not have the kind of control she was used to, as her unit was transferred to Navy control, which did not allow civilians to be in charge of a unit. “She had to take orders from a male officer, who she felt partly for career reasons, wanted to make South America a career story,” says Butler Greenfield. She was irritated too by the sloppiness of the FBI in interfering in code-breaking work, and felt that the agency had always looked at her with disdain and in a sexist light, yet still demanded her help because of her indispensable talents. It was a continuation of how she had been treated for much of her career, says Fagone. “She was always fixing messes men had created or solving problems they could not solve.”

But her contribution was singular. As the Americans were fighting in one theater of war in the Pacific, fears were also growing about the threat of Nazi-backed coups and insurrections in South America, home to several resource-rich countries that were strategically important for the U.S. to keep onside. Friedman decrypted messages that had been sent using the infamous German Enigma machines, uncovering an entire spy network across South America, and discovering the identity, codename and codes of its ringmaster, Johannes Siegfried Becker. “Elizebeth was his nemesis. She successfully tracked him where every other law enforcement agency and intelligence agencies failed. She did what the FBI could not do,” says Fagone. After the spy ring was crushed, Argentina, Bolivia and Chile definitively broke with Axis powers and sided with Allied powers, eliminating the threat that the western hemisphere would fall.

The lie that ended up in history books

Although the FBI turned to Friedman for her help, she didn’t receive any credit for her role in smashing the Axis spy ring throughout South America. Instead, the achievement was claimed by J. Edgar Hoover, who claimed that the FBI had led the code-breaking effort and thus erased the contribution of Friedman and her team. “It was a lie, but it was a lie that worked, and it was the lie that ended up getting written into the history books,” says Fagone. Friedman signed a Navy oath promising her silence until her death, which was in 1980, and stayed true to it for all those decades.

“I think a lot of professional women today can relate to her experiences—she did all this important work and got very little credit,” says Fagone. A quick look back through TIME’s own archives shows how little was known about her contribution to World War II in particular, owing to Hoover’s taking credit and Friedman’s loyalty to her oath. A 1956 profile of William in TIME listed his “lofty honors” and awards for his contributions to break the cipher of the “PURPLE” machine, and referred to Elizebeth as an “assistant cipher clerk.”

Decades after her death, in 2008, documents about Friedman’s involvement were finally declassified; the couple also left an extensive archive, including letters and photographs, to the George C. Marshall Foundation in Lexington, Va., some of which are featured in The Codebreaker. “We’re in an era when we realize that there are so many stories that were not told historically,” says filmmaker Chana Gazit. “If we missed Elizebeth’s story, who else are we missing?”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com