Mario Smith first broke out in cold sweats on Nov. 21. He thought it was just exhaustion from working maintenance shifts at the Gus Harrison Correctional Facility in Adrian, Mi., where he’s been incarcerated since 2018.

But then guards came to his cell on Nov. 23, he says, and told him to report to another area of the prison. Smith knew then that he must have tested positive for COVID-19. “I feared for my life,” Smith tells TIME. The 37-year-old has asthma, high blood pressure and obesity, putting him at increased risk for severe illness and complications from the virus. Sentenced to life in prison when he was 17, Smith recently had his sentence reduced to 30 years minimum, but remembers worrying that he might die in prison after all.

Smith is one of at least 1,400 inmates at Gus Harrison Correctional Facility—and over 20,000 incarcerated Americans throughout the state of Michigan—who have tested positive for COVID-19 since the pandemic began. As of Dec. 28, 108 inmates have died from the virus throughout the state, six of whom were incarcerated in the Gus Harrison Correctional Facility.

In a statement sent to TIME, the Michigan Department of Corrections says that the facility has “taken a number of measures to protect against COVID, as well as slow the spread.” These measures include testing prisoners and staff members every week and suspending in-person visitation in March.

“We clean every facility with disinfectant and bleach every day and common touchpoints are cleaned multiple times a day. Prisoners are cohorted based on [their] COVID status so we keep positive and negative prisoners away from one another,” the statement says. “We paused programming and classes for the past few weeks at every prison to reduce possible spread.”

From the moment the virus began to spread across the U.S., experts and epidemiologists predicted that incarcerated people would be particularly vulnerable. Risk factors they face include the close proximity in which inmates live and congregate, prison transports, where inmates tend to be shackled close together, and a lack of consistent access to cleaning supplies. “They are basically the perfect conditions for superspreading events,” Dr. Thomas Inglesby, director of Johns Hopkins’ Center for Health Security, told NPR.

And many of the worst projections have since come true: there have been outbreaks at more than 850 jails and prisons in the country, putting many of the over 2 million people incarcerated in the U.S. at risk of infection. Dr. Ross MacDonald, chief physician of New York’s Rikers Island, told TIME in March simply that, “the right preventive measures don’t exist to stop the spread of this virus in [jail and prison facilities].”

A December study from the National Commission on COVID-19 and Criminal Justice (NCCCJ), a nonpartisan criminal justice group, reveals that the infection rate has been three times higher in the prison population compared to that of the general public, while the mortality rate has been double. At least 275,000 incarcerated people have tested positive for COVID-19, and more than 1,700 have died, according a joint report from The Marshall Project and The Associated Press. The true toll is likely to be higher still, as data sets are inconclusive due to a lack of consistency across states in sharing prison and jail data.

“We weren’t prepared,” says Alberto Gonzales, co-chair of the NCCCJ and former U.S. Attorney General under President George W. Bush. “The fact of the matter is you can only do so much with respect to prisons and jails in terms of preparing for something like this.”

Gonzalez and other experts say the scarcity in data points to a lack of oversight from the federal government. “You have so many different government agencies that have been trying to manage COVID,” adds Loretta Lynch, co-chair of the NCCCJ and former U.S. Attorney General under President Barack Obama. “There was no overarching strategy to gauge the impact on the correctional system at large.”

In October, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a suit against the federal government for its “failed response to the spread of COVID-19 in prisons and jails.”

“COVID has been uniquely awful for people in jails and prisons,” says Somil Trivedi, senior staff attorney in the Criminal Law Reform Project at the ACLU. “That includes staff who are forced to go in there for their livelihoods… and then forced to go back out into the community.”

At the Toledo Correctional Institution in Toledo, Ohio, 172 staff members had tested positive as of Dec. 27—a large enough portion of the prison’s workforce that the Ohio National Guard has been called in to help run the facility, local news channel WTOL 11 reports.

Forty-five-year-old David Easley began suffering from loss of taste and smell, extreme fatigue and chills a few weeks ago, he says. He tested positive for the virus shortly afterwards and was put in quarantine for 14 days. (He’s since been released.) At least 87 inmates in the Toledo Correctional Institution have tested positive since the pandemic began. Easley alleges the prison only tests inmates who report symptoms; a representative for the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction (ODRC) disputes this, however, telling TIME that prison doctors have “the authority to order as much testing as [they need] for clinical and/or surveillance reasons.”

“Weekly wastewater monitoring” is being undertaken at Ohio correctional facilities, a statement from the ODRC provided to TIME claims, which “is a tool that allows us to detect the presence of COVID-19 among the staff or inmate population and make the necessary operational changes in order to help protect the health and safety of those working and living inside of our prisons.”

“The health and safety of our staff and the incarcerated population continues to be the top priority of the agency. COVID-19 presents unique challenges in a congregate setting such as a prison,” the statement continues. “All applicable CDC guidelines in have been implemented inside our prisons, and in many cases those things were put in place even before they were official CDC recommendations.”

Both Easley and Smith say they’re not surprised they caught COVID-19. “They’ve got us bunched up together… There’s no social distancing at all,” says Smith of the conditions he is being held in. “We share day rooms, we share showers. We share practically everything.”

Smith says he was moved to another area of the prison to quarantine after he tested positive. He says was given vitamins but otherwise was told essentially to wait to recover, he says. He had aches, chills and says he lost his sense of taste and smell. Nearly everyone he knows in the prison has also tested positive at this point, he adds. “Pick a prisoner,” he says. “We all have it.”

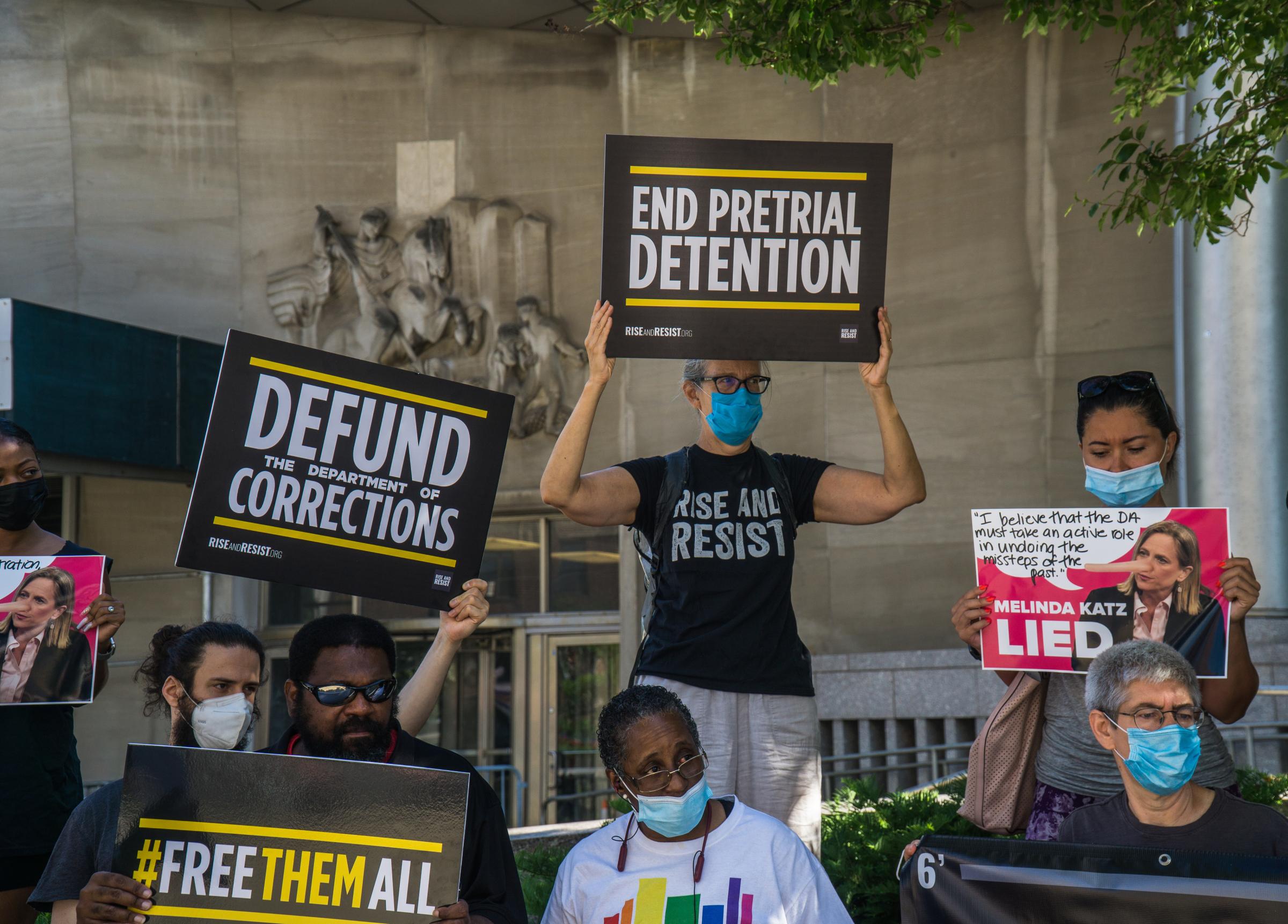

One consistent call for change advocated by experts and activists to offset the spread of the virus in prisons and jails has been to release as many inmates as possible. “The primary fix is to release everybody who you can possibly release safely,” Trivedi says. “To cut down, thin out the population within the facilities to allow for social distancing and mask-wearing to actually work.”

Nationally, this year’s prison population has been reduced by about 5%, a drop attributed in large part to COVID containment protocols. In its statement to TIME, the MDOC says that over 7,000 prisoners in the state have been paroled, “beginning with the elderly and those with preexisting conditions.”

“The only prisoners who are parole eligible who have not been released around the state are those who the board feels would be a danger to society if released,” the statement adds.

In response to a separate ACLU suit on Dec. 11, a California judge ordered a 50% reduction in the jail population in Orange County as COVID-19 numbers in the jails soared. Bu the sheriff has since refused to obey the order. As of Dec. 27, 1,872 detainees in the jail had tested positive and one had died, according to the Orange County Register.

Along with calls to release more inmates, activists and experts say there needs to be more testing in prisons and jails, a better distribution system of personal protective equipment (PPE) for inmates and those working in correctional facilities, and priority access to vaccines offered to at-risk prisoners.

And experts believe that the presence of the virus has raised more wide-reaching questions about the criminal justice system. “This is an opportunity to look at whether or not we are effectively using our prison and jail system within the overall criminal justice system,” Lynch says. “We see the public health challenges exacerbated in overcrowded [prison and jail] facilities.”

Smith eventually recovered but says he is still being housed in a COVID-19 unit. He worries about catching the virus again.

“I know if I’m in prison, I’m going to catch it again. That’s just bottom line,” he says. “I might not be so lucky the next time around.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Madeleine Carlisle at madeleine.carlisle@time.com and Josiah Bates at josiah.bates@time.com